- Department of Neurosurgery, Desert Regional Medical Center, Palm Springs, CA,

- Department of Internal Medicine, MacNeal Hospital Loyola University, Berwyn, IL,

- Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, Midwestern University, Glendale, AZ,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Mohammad Arsal Arshad, Department of Neurosurgery, Desert Regional Medical Center, Palm Springs, CA, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_181_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Mohammad Arsal Arshad1, Louis Samuel Reier1, James B. Fowler1, Hamid Hadi1, Hassan Khan2, Usman Beg3, Brian Fiani4. Report of cerebral vasospasm as a complication of intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage following traumatic lumbar puncture. 08-Apr-2022;13:128

How to cite this URL: Mohammad Arsal Arshad1, Louis Samuel Reier1, James B. Fowler1, Hamid Hadi1, Hassan Khan2, Usman Beg3, Brian Fiani4. Report of cerebral vasospasm as a complication of intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage following traumatic lumbar puncture. 08-Apr-2022;13:128. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/report-of-cerebral-vasospasm-as-a-complication-of-intracranial-subarachnoid-hemorrhage-following-traumatic-lumbar-puncture/

Abstract

Background: This case report is the first documented and illustrated case of the identification and treatment of intracranial vasospasm as a sequalae of traumatic lumbar puncture (LP). LP is a routine procedure performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Although rare, this procedure has risks and complications that should be considered before performing.

Case Description: A 58-year-old male was found to have intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) 2 days after a traumatic LP which occurred in the setting of subtherapeutic international normalized ratio. During his hospitalization, the patient developed both clinical and radiographic signs of vasospasm. He was taken for angiography, which demonstrated significant vasospasm of bilateral middle cerebral arteries and bilateral anterior cerebral arteries. All vasospasms resolved and the patient improved clinically after intra-arterial spasmolytic therapy.

Conclusion: LP is a routine procedure with complications that are often overlooked. The authors describe intracranial vasospasm from traumatic LP before correction of patient’s coagulopathy. Cases with similar hemorrhage occurring in the spine resulting in non-aneurysmal SAH and vasospasm were reviewed.

Keywords: Cerebral vasospasm, Lumbar puncture, Spinal hematoma

INTRODUCTION

The lumbar puncture (LP) was first reported by Quinke in the late 19th century. Today, this technique has become an essential tool providing both diagnostic and therapeutic purpose. It is routinely used for the diagnosis of a variety of conditions including meningitis, encephalitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), central nervous system vasculitis, autoimmune conditions, paraneoplastic syndromes, and some intracranial tumors.[

Understanding lumbar spine anatomy is vital in performing a safe LP. As the spinal needle is inserted in the lumbar spine, it will pierce the skin, subcutaneous tissue, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flavum, epidural space, dura, arachnoid, and ultimately into the subarachnoid space.[

Contraindications to performing a LP include infection near the site of the LP, posterior fossa mass with increased intracranial pressure, and coagulopathy. Risks of LP include spinal headache with intracranial hypotension, nerve root irritation, infection, brain stem herniation, and bleeding complications.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 58-year-old male with medical history of autoimmune deficiency syndrome, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, polysubstance abuse disorder, psychogenic movement disorder, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome presented to emergency department (ED) with altered mental status.

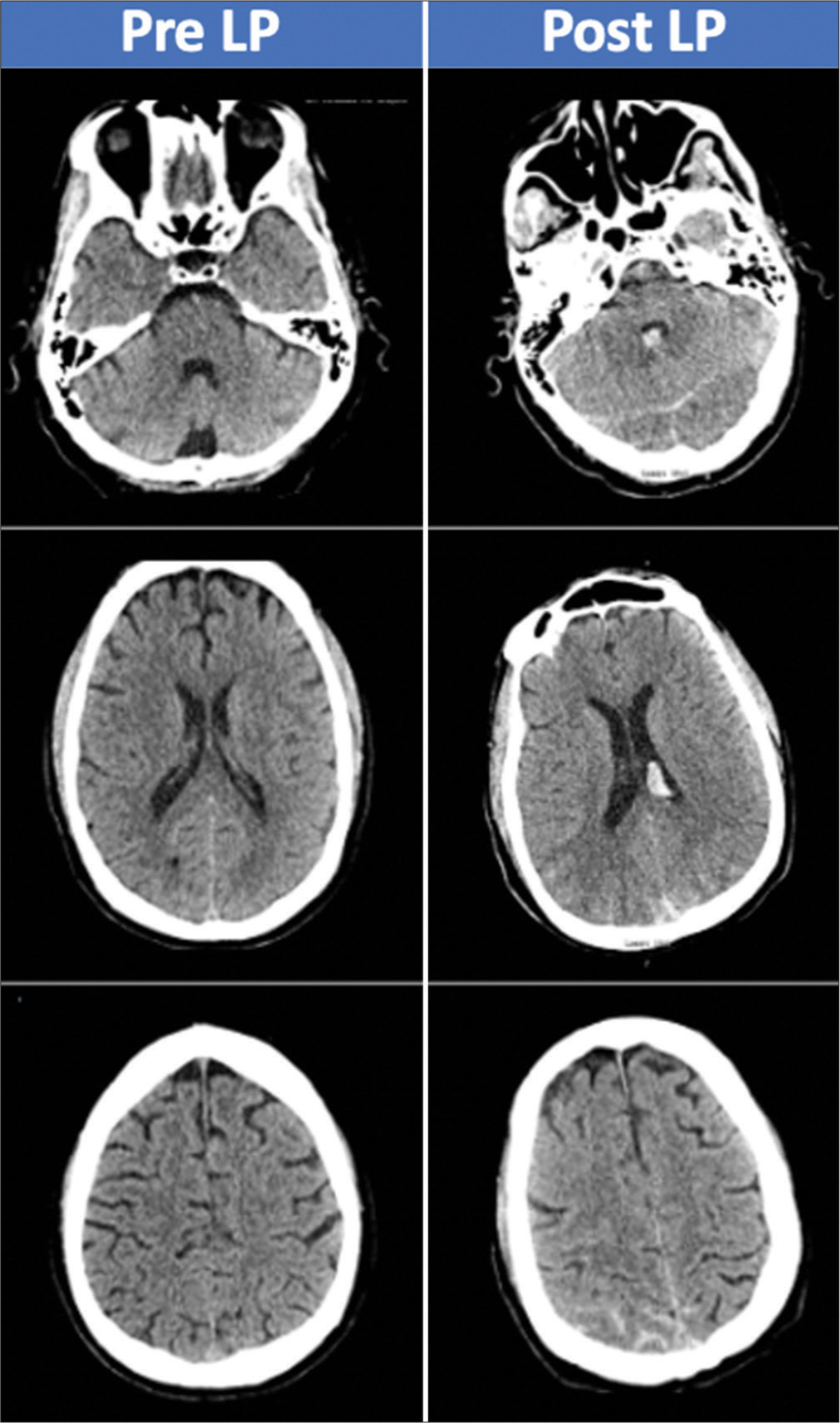

Initial computed tomography (CT) head without contrast was negative for hemorrhage. The ED proceeded with performing a LP to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for the diagnostic purpose of ruling out meningitis and HIV encephalitis. The LP yielded 20cc of bloody CSF. Of note, patient was on Coumadin for antiphospholipid syndrome and had an international normalized ratio of 2.0 and prothrombin time of 19.8. The ED failed to reverse his warfarin before performing the LP and the patient developed headache soon after, which sustained for the next few days. A second CT of the head without contrast was completed 48 h after the LP, for sustained headache and development of somnolence, which demonstrated diffuse SAH with intraventricular extension [

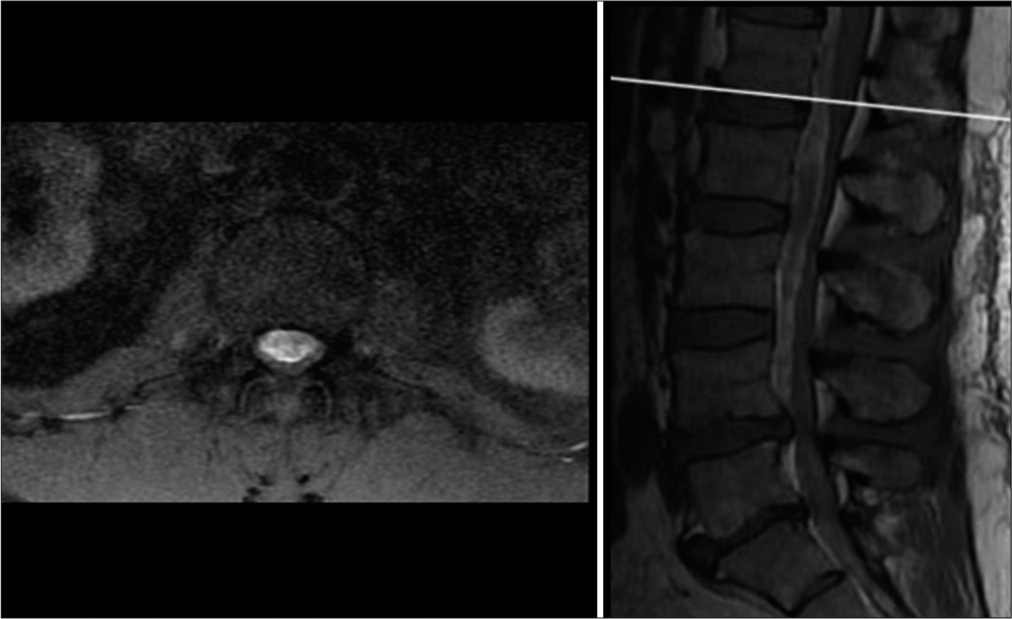

The patient subsequently developed low back pain, lower extremity weakness with radiculopathy, and urinary retention. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine demonstrated ventral extra-axial hematoma measuring 1.3 cm with compression of the cauda equina most severely at L2-L3 level [

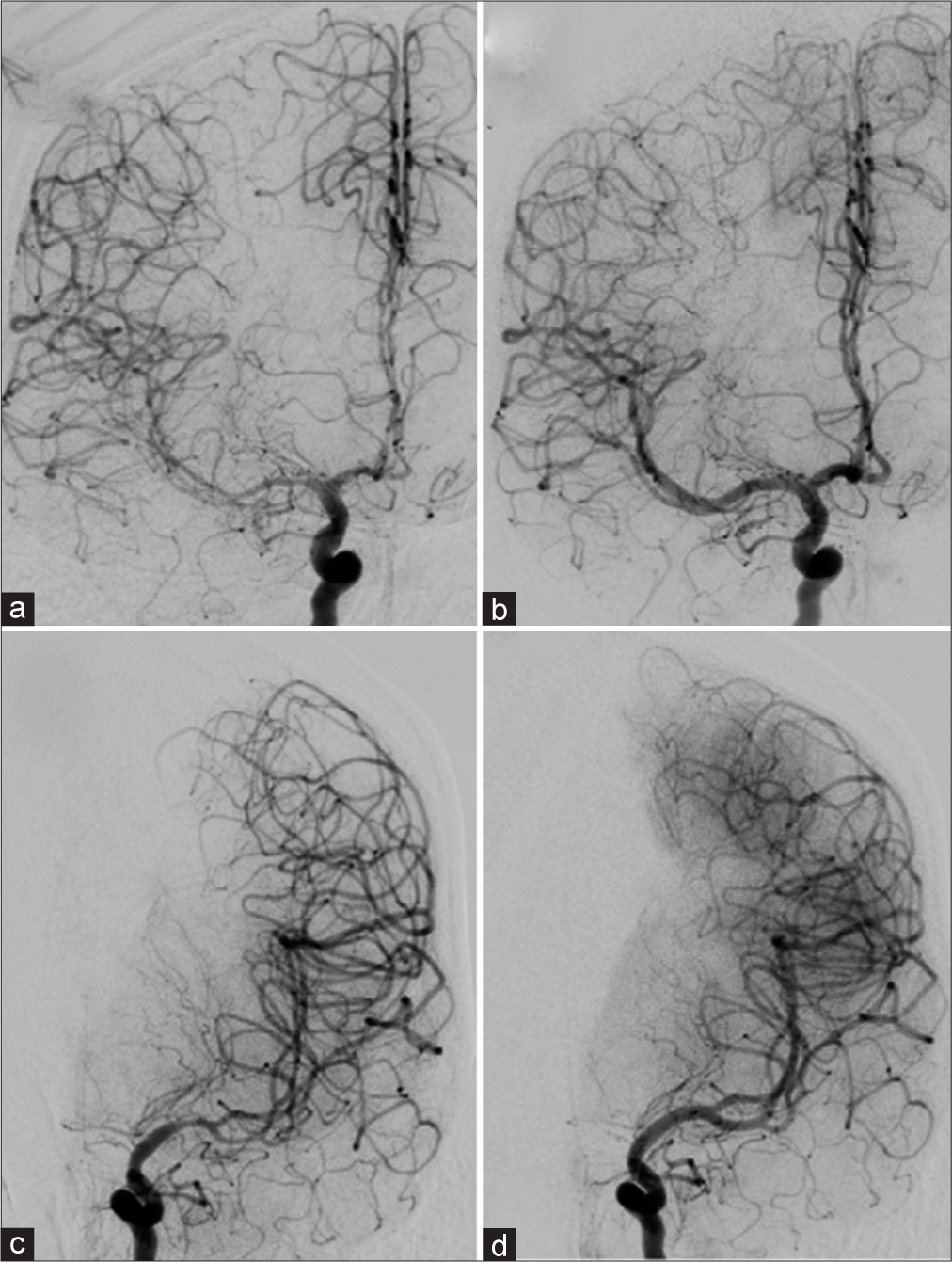

The patient’s mental status remained altered postoperatively with additional deficits of the upper extremity weakness on postbleed day 13. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) demonstrated elevated intracranial velocities (right middle cerebral arteries [MCA] velocity 251 cm/s, right posterior cerebral artery velocity 104.1 cm/s, and left MCA velocity 162.1 cm/s). Lindegaard ratio was 8.7 and 4.6 on the right and left, respectively. CT angiogram revealed moderate-to-severe narrowing of bilateral MCA and anterior cerebral arteries vessels as well as moderate narrowing of the basilar artery. Patient was started on hyperdynamic therapy and underwent a cerebral angiogram for delivery of intra-arterial spasmolytic therapy, which resolved the radiographic vasospasms [

Figure 3:

Cerebral angiogram, pre and post intra-arterial vasospasm treatment (a) right internal carotid artery (ICA) frontal projection pretreatment demonstrating moderate-to-severe vasospasm of the M1 and M2 segments of the MCA. ACA demonstrates mild-to-moderate vasospasm (b) right ICA frontal projection demonstrating improved vessel lumen caliber posttreatment (c) left ICA frontal projection demonstrates moderate-to-severe M1 and mild M2 vasospasm pretreatment (d) left ICA frontal projection demonstrating improved vessel lumen caliber posttreatment.

The patient was discharged from the hospital 45 days after admission after completing a 3-week course in the neurocritical care unit for close observation for any subsequent vasospasm and followed by rigorous inpatient physical therapy. At discharge, the patient’s upper extremity weakness had resolved, but he remained paretic in the lower extremities. He was able to feed and groom himself independently and transfer himself from bedside to wheelchair (modified Rankin score [mRS] 4). At 2-year follow-up, the patient had improvement in his lower extremity strength with some deficits noted (mRS 2).

DISCUSSION

Traumatic LP in a patient taking anticoagulants is one etiology of spinal hematomas,[

There has been extensive research regarding the pathogenesis of arterial vasospasm. Some studies provide evidence that particular substances found in CSF after SAH, namely, oxyhemoglobin found in xanthochromic CSF, are the main mediators of cerebral vasospasm.[

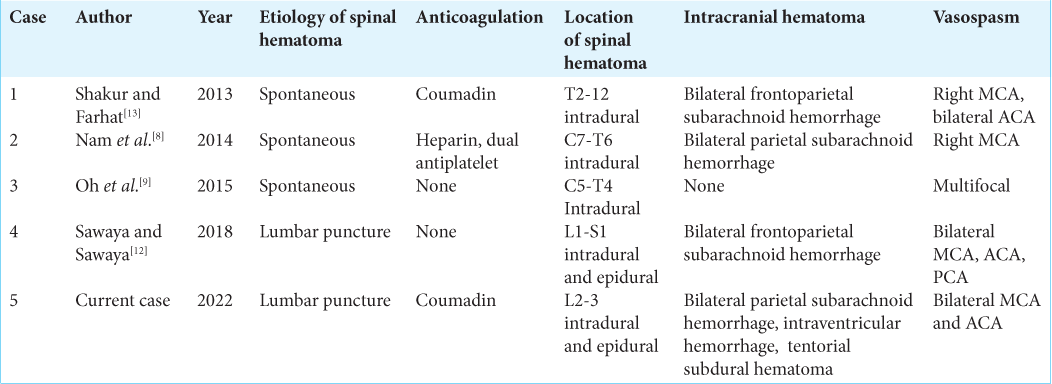

There have only been four other cases reported of spinal hematoma resulting in intracranial vasospasm as listed in [

CONCLUSION

LP is not an emergent nor benign procedure. Therefore, proper indications, contraindications, and all risks should be considered before performing it, especially in a coagulopathic patient. We report a case of traumatic LP resulting in a patient developing nonaneurysmal SAH and subsequent intracranial vasospasm. This complication could have been avoided in this case if, first, the indication and necessity for LP were considered and, second, if the risk of completing the procedure with coagulopathy was considered. Our case demonstrates the successful and timely treatment necessary to improve outcomes for patients who develop this complication.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Adler MD, Comi AE, Walker AR. Acute hemorrhagic complication of diagnostic lumbar puncture. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001. 17: 184-8

2. Armon C, Evans RW. Addendum to assessment: Prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches: Report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005. 65: 510-2

3. Breuer AC, Tyler HR, Marzewski DJ, Rosenthal DS. Radicular vessels are the most probable source of needle-induced blood in lumbar puncture: Significance for the thrombocytopenic cancer patient. Cancer. 1982. 49: 2168-72

4. Chakraverty R, Pynsent P, Isaacs K. Which spinal levels are identified by palpation of the iliac crests and the posterior superior iliac spines?. J Anat. 2007. 210: 232-6

5. Frederiks JA, Koehler PJ. The first lumbar puncture. J Hist Neurosci. 1997. 6: 147-53

6. Gustafsson H, Rutberg H, Bengtsson M. Spinal haematoma following epidural analgesia. Report of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis and a bleeding diathesis. Anaesthesia. 1988. 43: 220-2

7. Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W. Spinal hematoma: A literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2003. 26: 1-49

8. Nam KH, Lee JI, Choi BK, Han IH. Intracranial extension of spinal subarachnoid hematoma causing severe cerebral vasospasm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014. 56: 527-30

9. Oh JH, Jwa SJ, Yang TK, Lee CS, Oh K, Kang JH. Intracranial Vasospasm without Intracranial Hemorrhage due to Acute Spontaneous Spinal Subdural Hematoma. Exp Neurobiol. 2015. 24: 366-70

10. Perrini P, Pieri F, Montemurro N, Tiezzi G, Parenti GF. Thoracic extradural haematoma after epidural anaesthesia. Neurol Sci. 2010. 31: 87-8

11. Sandoval M, Shestak W, Stürmann K, Hsu C. Optimal patient position for lumbar puncture, measured by ultrasonography. Emerg Radiol. 2004. 10: 179-81

12. Sawaya C, Sawaya R. Central nervous system bleeding after a lumbar puncture: Still an ongoing complication. Am J Case Rep. 2018. 19: 1103-7

13. Shakur SF, Farhat HI. Cerebral vasospasm with ischemia following a spontaneous spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Case Rep Med. 2013. 2013: 934143