- Department of Neurosurgery, Centre Clinical De Soyaux, Soyaux, France

Correspondence Address:

Keyvan Mostofi, Department of Neurosurgery, Centre Clinical De Soyaux, Soyaux, France.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_72_2025

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Mostofi K. Sarah Mutomb, the first female neurosurgeon in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Surg Neurol Int 28-Feb-2025;16:70

How to cite this URL: Mostofi K. Sarah Mutomb, the first female neurosurgeon in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Surg Neurol Int 28-Feb-2025;16:70. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13415

Dear Sir,

In Kisangani, Meditz et al.,[

Certainly, there is still marked inequality for African women surgeons, particularly for neurosurgeons in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Female neurosurgeons in the DRC typically experience a lack of respect, are subject to harassment, and are typically offered inferior professional roles and lower salaries than their male counterparts.[

LIFE AND CAREER

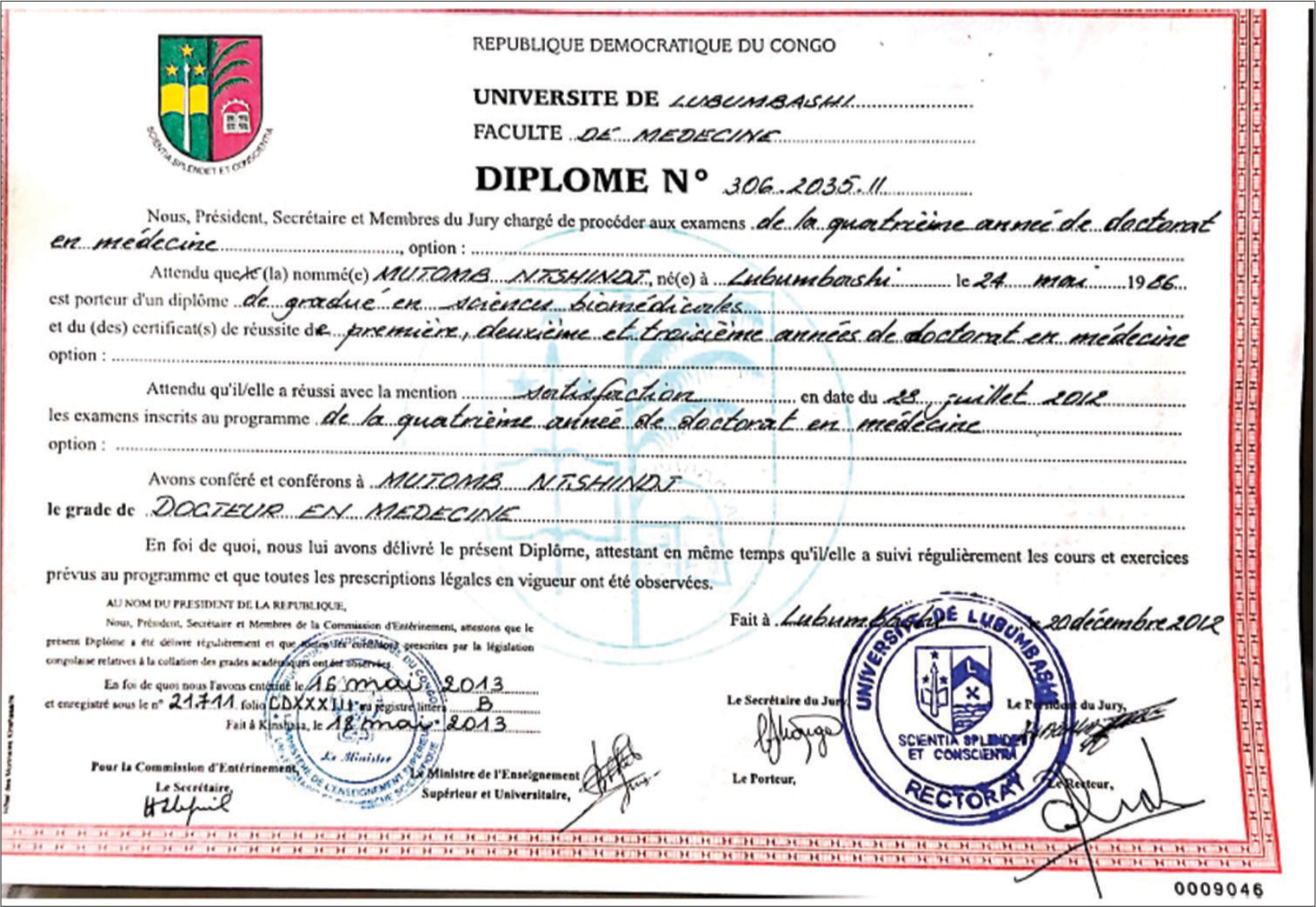

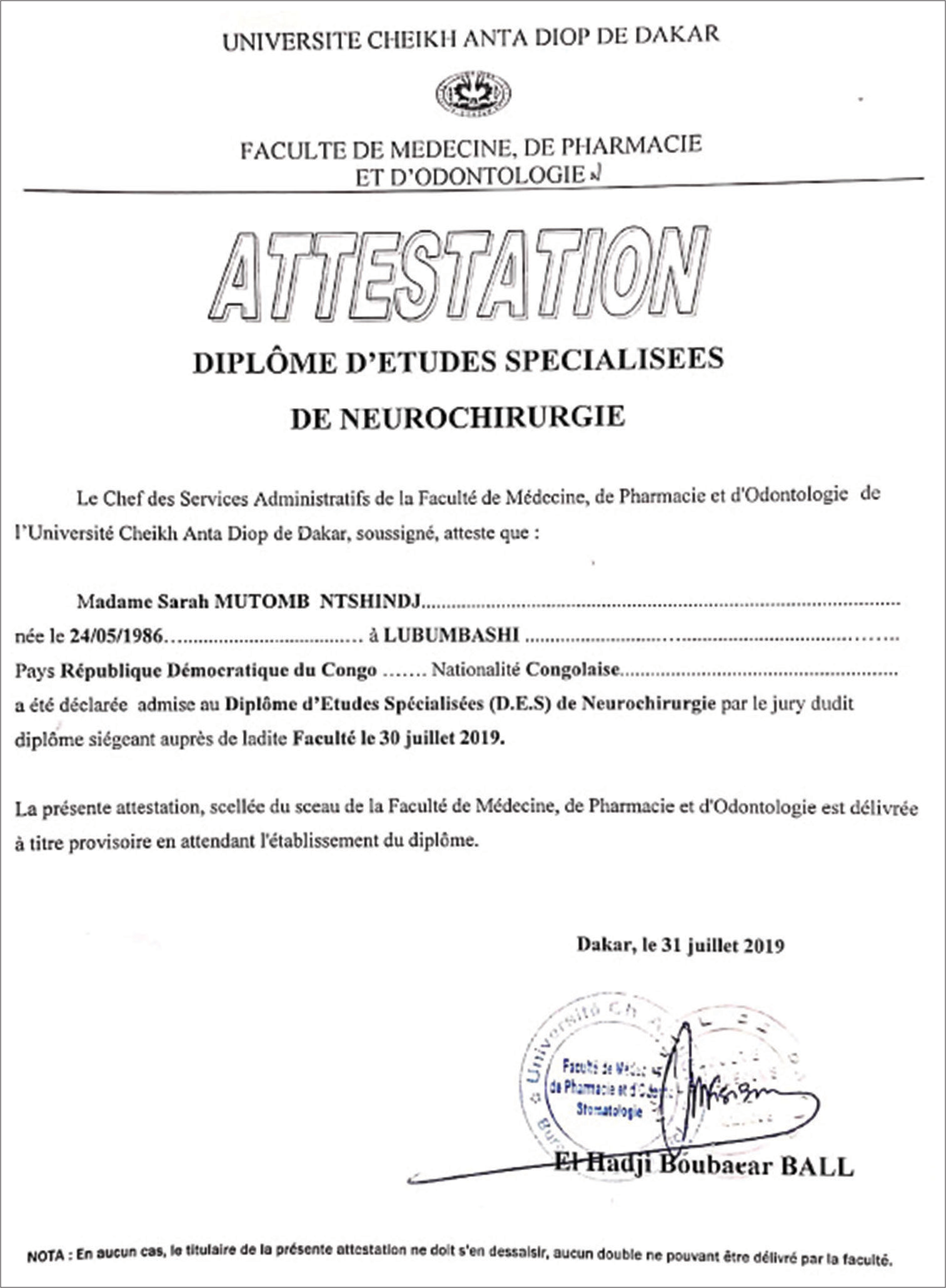

Sarah Mutomb was born in 1986 in Lubumbashi (i.e., the second largest city in the DRC) to a father who was a surgeon. She received a baccalaureate in Biology/Chemistry in 2004 and went to Medical School at the University of Lubumbashi, receiving her MD degree in 2012 [

DISCUSSION

The DRC is the second largest nation in Africa, with a population of 111 million; 51% are women, and 48% are under the age of 15.[

CONCLUSION

Sarah Mutomb, the first female neurosurgeon in the DRC, overcame multiple personal and professional obstacles put in her way to become the consummate neurosurgical professional that she is today.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Sarah Mutomb for generously taking the time to respond to his inquiries through WhatsApp on multiple occasions. Furthermore, he is grateful to her for providing him with the pictures that he has included in this paper.

References

1. Addati L, Cattaneo U, Pozzan E, editors. Care at work: Investing in care leave and services for a more gender equal world of work. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO); 2022. p. 62-186

2. Assemblée nationale. Constitution de la République Démocratique du Congo. Available from: https://media.unesco.org/sites/default/files/webform/r2e002/30fc959de50075fb86d6f23e93148d2f48056a21.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

3. Bleck J, Van de Walle N. Electoral politics in Africa since 1990: Continuity in change. Cambridge, Royaume-Uni: Cambridge University Press; 2019. p. 283-4

4. Cordell DD, Wiese BM, editors. History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. United States: Britannica Encyclopedia; 2025. p. 352-3

5. International Labour Organization (ILO). Assessing the current state of the global labour market: Implications for achieving the Global Goals. Available from: https://ilostat.ilo.org/assessing-the-current-state-of-the-global-labour-market-implications-for-achieving-the-global-goals [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

6. Jesuyajolu DA, Okeke CA, Obuh O. The challenges experienced by female surgeons in Africa: A systematic review. World J Surg. 2022. 46: 2310-6

7. Journal Official de la république Démocratique du Congo. Code de la Famille. Available from: https://www.leganet.cd/legislation/codedelafamille/table.htm [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

8. Kabulo KD, Mutomb NS, Yengayenga K, Mudegereza SP, Neba GN, Beltchika A. Neurosurgery in the Democratic Republic of Congo: A historical review. Egypt J Neurosurg. 2024. 39: 73

9. Meditz SWMerrill T. Federal Research Division. Zaire: A country study. Available from: https://www.loc.gov/item/94025092 [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

10. Muswamba RM, editors. Le travail des femmes en République démocratique du Congo: Exploitation ou promesse d’autonomie? Paris, Unesco, coll. Les classiques des sciences sociales (version numérisée par Jean-Marie Tremblay. Canada: CEGEP de Chicoutimi; 2006. p. 129-30

11. Pachi D, Barrett M. Perceived effectiveness of conventional, non-conventional and civic forms of participation among minority and majority youth. Human Affairs. 2012. 22: 345-59

12. Plan International. Bridging the Digital Divide. Available from: https://plan-international.org/qualityeducation/bridging-the-digital-divide [Last accessed on 2023 May 28].

13. Radio Opaki. Kinshasa: Les femmes médecins dénoncent la nonreprésentativité de la femme à tous les niveaux. Available from: https://www.radiookapi.net/2022/03/08/actualite/societe/kinshasales-femmes-medecins-denoncent-la-non-representativite-de-la [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 08].

14. Sur Parline: Plateforme de données ouvertes de l’UIP. Available from: https://data.ipu.org/fr/parliament/CD/CD-UC01/elections/historical-data-on-women [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

15. UN Women Africa. Democratic Republic of Congo. Available from: https://africa.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/west-and-central-africa/democratic-republic-of-congo [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

16. United Nations Development Programme, report on human development. Available from: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-10/hdr23_full_report_0319_fr_v2_0.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17].

17. World economic for. Global Gender Gap Report 2023. 2023. p. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2023 [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 17]

18. World Health Organization’s Global Health Workforce Statisti, editors. OECD, supplemented by country data, Physicians (per 1,000 people)-Congo. Democratic Republic. 2018. p.