- Spine Services, Indian Spinal Injuries Centre, New Delhi, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_510_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Abhinandan Reddy Mallepally, Rajat Mahajan, Sandesh Pacha, Tarush Rustagi, Nandan Marathe, Harvinder Singh Chhabra. Spinal osteoid osteoma: Surgical resection and review of literature. 25-Sep-2020;11:308

How to cite this URL: Abhinandan Reddy Mallepally, Rajat Mahajan, Sandesh Pacha, Tarush Rustagi, Nandan Marathe, Harvinder Singh Chhabra. Spinal osteoid osteoma: Surgical resection and review of literature. 25-Sep-2020;11:308. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=10285

Abstract

Background: Osteoid osteoma (OO) is a rare benign tumor of the spine that involves the posterior elements with 75% tumors involving the neural arch. The common presenting symptoms include back pain, deformity like scoliosis, and rarely radiculopathy.

Methods: From 2011 to 2017, we evaluated cases of OO managed by posterior surgical resection while also reviewing the appropriate literature.

Results: We assessed five patients (three males and two females) averaging 36.60 years of age diagnosed with spinal OOs. Two involved the lumbar posterior elements, two were thoracic, and one was in the C3 lateral mass. All patients underwent histopathological confirmation of OO. They were managed by posterior surgical resection with/without stabilization. No lesions recurred over the minimum follow-up period of 24 months.

Conclusion: Surgical excision is the optimal treatment modality for treating spinal OOs. The five patients in this study demonstrated good functional outcomes without recurrences. Further, the literature confirms that the optimal approach to these tumors is complete surgical excision with/without radiofrequency ablation.

Keywords: Gross total resection, Osteoid osteoma, Posterior elements, Radiofrequency ablation, Resection, Spinal involvement, Tumor

INTRODUCTION

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is a benign tumor which accounts for 10–40% of spine tumors; the majority involve the lumbar spine (59%), and especially the neural arch (75%). Typical clinical presentations include night pain/back pain/stiffness markedly relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Treatment options for OO include conservative management with anti-inflammatory agents, surgical curettage, partial excision, marginal or gross total en bloc excision, and with/without radiofrequency ablation.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

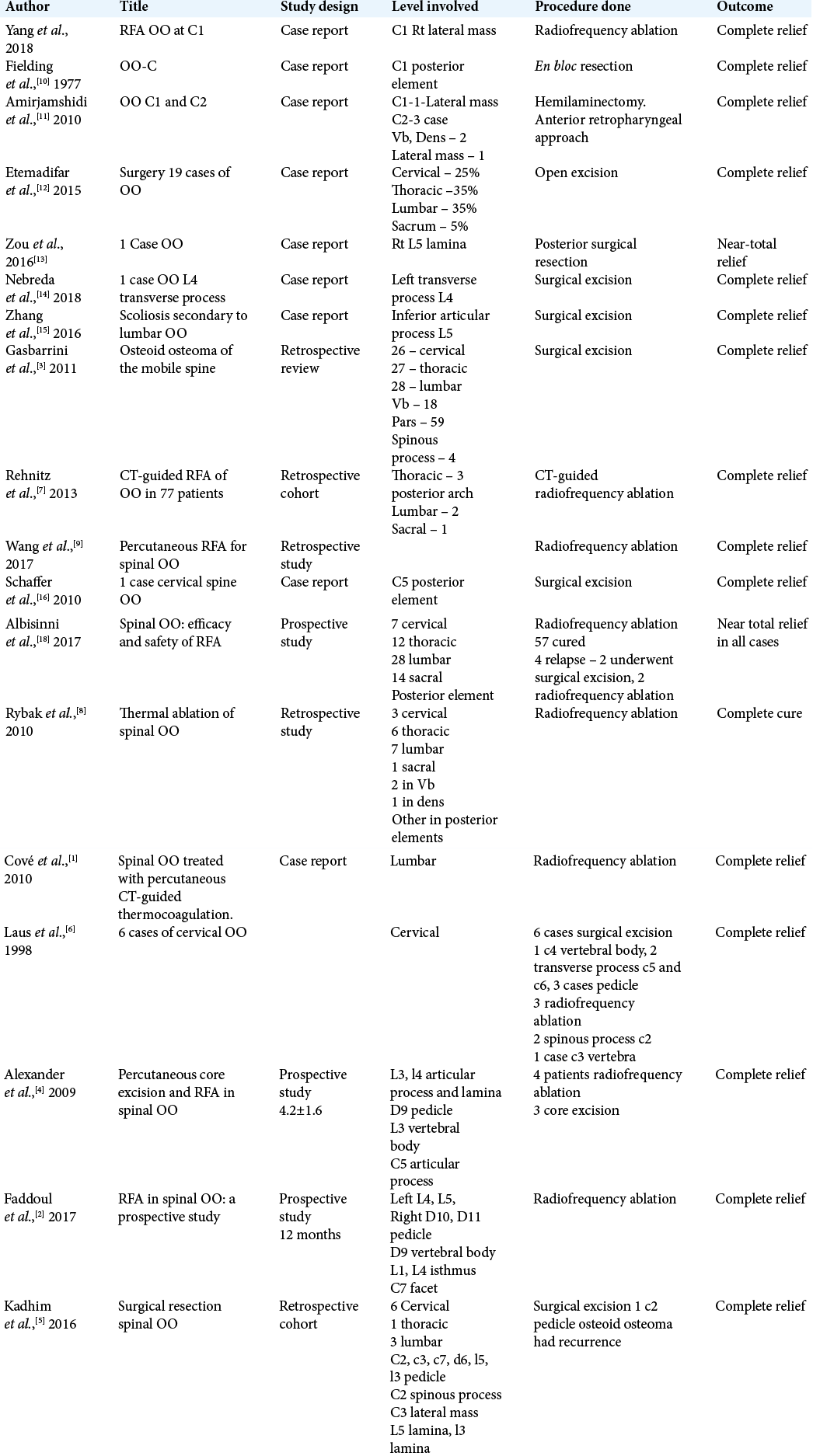

After approval from the Institutional Review Board, five patients’ clinical symptoms, radiological studies (MR/CT), surgical details (posterior decompressions/resections), outcomes/pain scores, and recurrence rates were studied from 2011 to 2017. We also did a literature review regarding the relevant articles in PubMed and Medline databases [

RESULTS

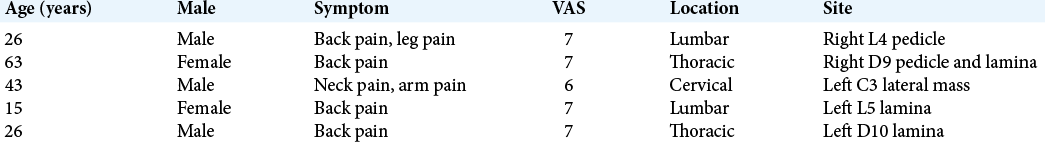

The five patients who all presented with back pain attributed to OO averaged 36.6 years of age and included three males and two females. Lesions were located in the posterior elements of the lumbar (two patients), thoracic (two patients), and cervical spine (one patient) [

Case 1

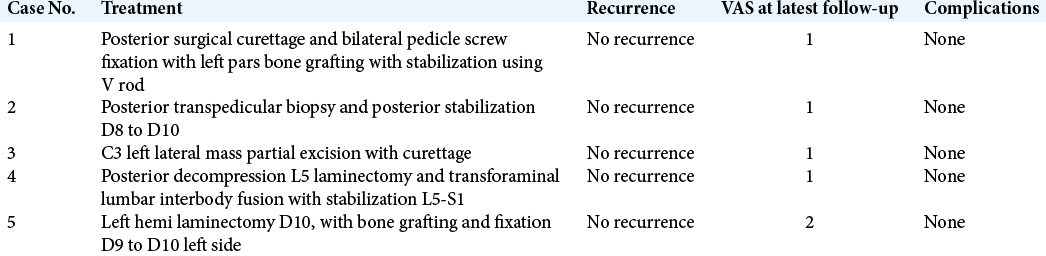

A 26-year-old male presented with low back pain with CT scan showing a L4 pedicle lesion with lysis of pars [

Figure 1:

(a) Preoperative sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI showing osteoid osteoma at L4 pedicle with pars lysis. (b) Sagittal and axial CT scan showing osteoid osteoma involving L4 pedicle with lysis of pars (c). (c) Postoperative X-ray showing bilateral pedicle screw fixation with the left pars bone grafting.

Case 2

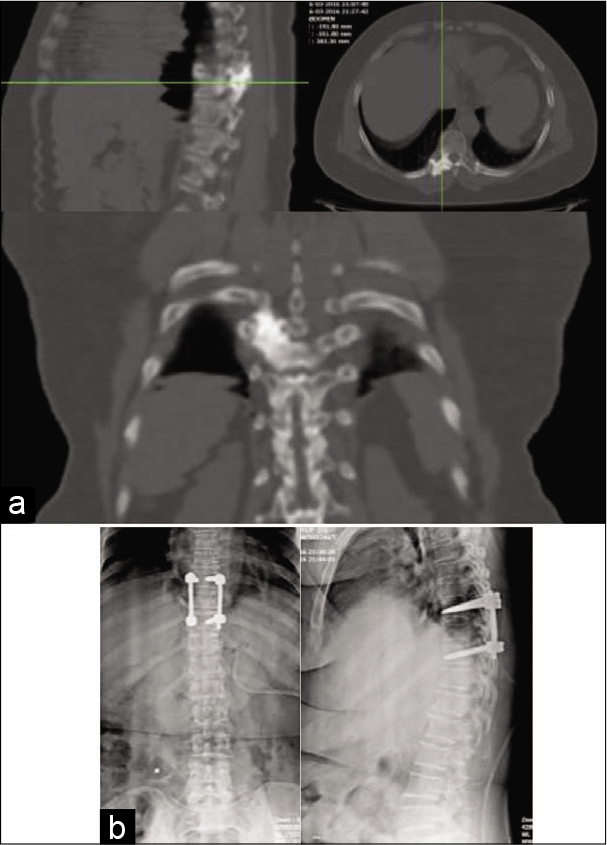

A 63-year-old female presented with back pain with CT scan showing a hyperdense sclerotic lesion at the right D9 pedicle/ lamina. Transpedicular biopsy with posterior D8-D10 fusion was done [

Case 3

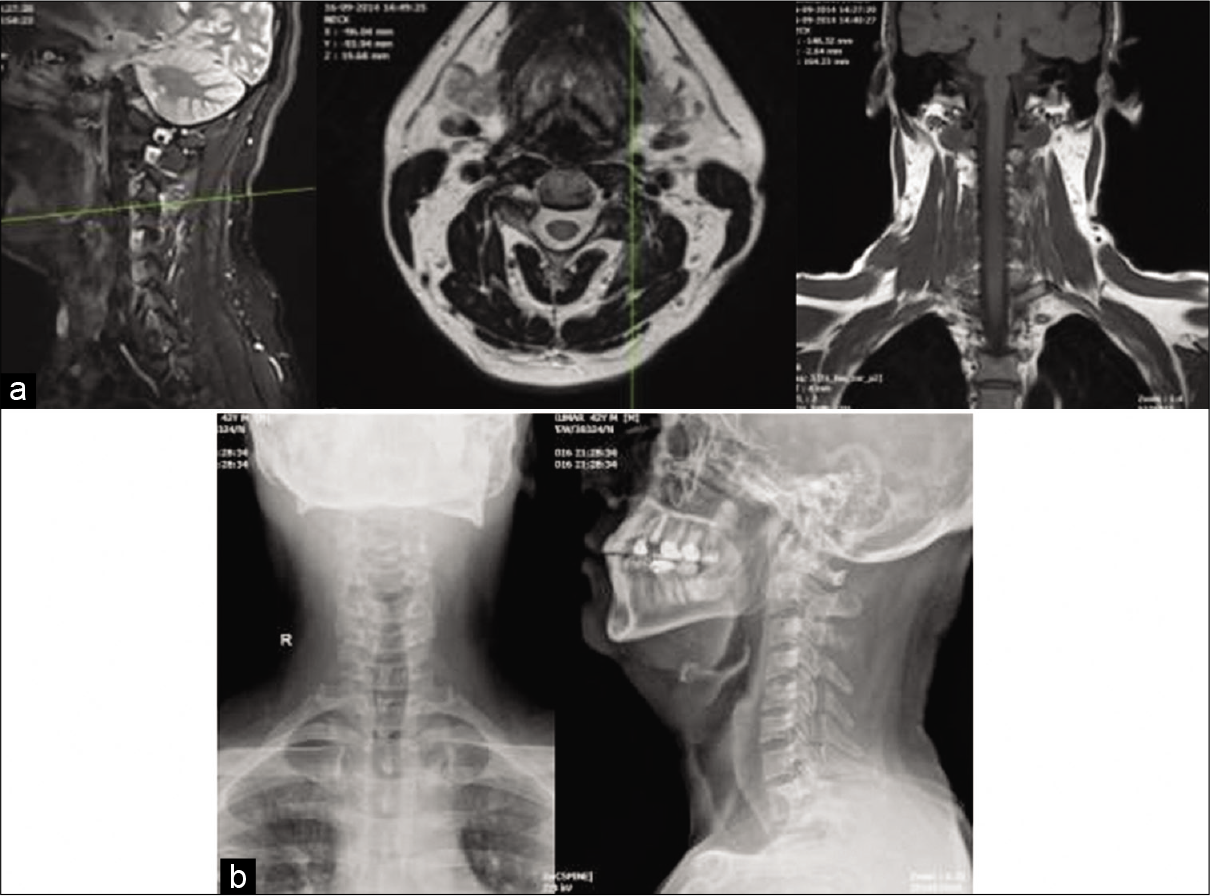

A 43-year-old male presented with a CT scan demonstrating hyperdense left sided C3 lateral mass for which he underwent a curettage without instrumentation [

Case 4

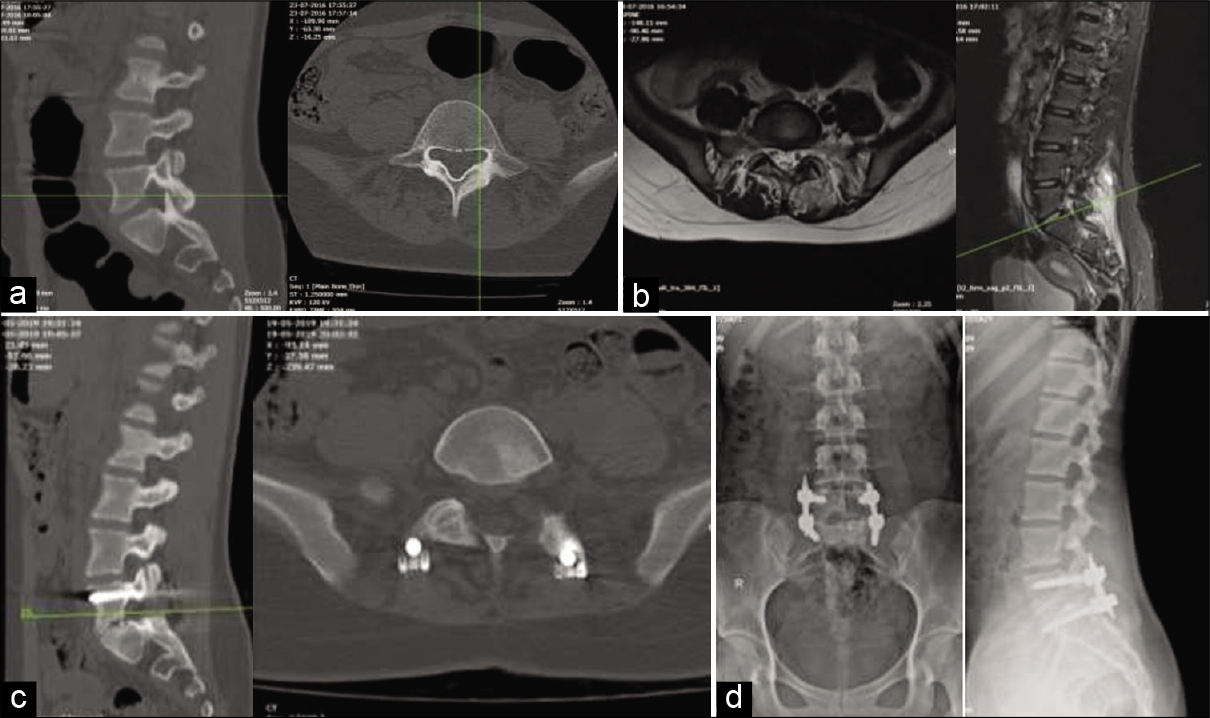

A 15-year-old female presented with a left-sided L5 laminar lesion for which she underwent decompression in the form of L5 laminectomy with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion [

Figure 4:

(a) Sagittal and axial CT scan demonstrating osteoid osteoma involving left L5 pedicle and lamina. (b) Sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI showing lesion involving left L5 pedicle and lamina. (c) Postoperative CT scan demonstrating complete excision of lesion. (d) Postoperative AP and lateral X-ray showing pedicle screw fixation (L5, S1).

Case 5

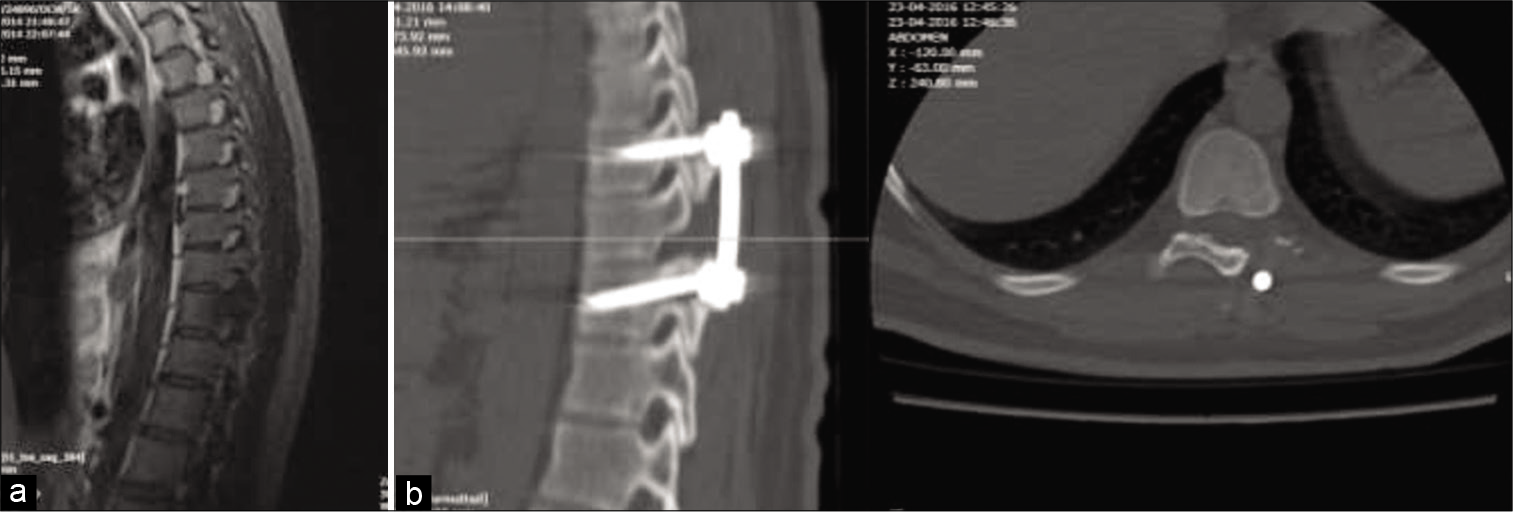

A 26-year-old male with pain in thoracic region underwent left T10 hemilaminectomy with bone grafting and D8 to D10 fusion [

DISCUSSION

OO is a benign skeletal neoplasm consisting of a highly vascularized nidus of connective tissue surrounded by sclerotic bone. The size of the nidus (15 mm) distinguishes it from osteoblastoma. OO comprises 10% of all benign bone tumors and only 1% of all spinal tumors. It mainly involves the lumbar spine with predilection for posterior elements seen in 75% of cases.[

Surgical intralesional excision has been the commonly accepted treatment for a long time.[

CONCLUSION

OO is a rare benign tumor, commonly involving the posterior elements of the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine in descending order of frequency. Gross total surgical excision with/without radiofrequency ablation is the optimal treatment, resulting in good functional outcomes and rare recurrences.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Cové JA, Taminiau AH, Obermann WR, Vanderschueren GM. Osteoid osteoma of the spine treated with percutaneous computed tomography-guided thermocoagulation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000. 25: 12836

2. Faddoul J, Faddoul Y, Kobaiter-Maarrawi S, Moussa R, Rizk T, Nohra G. Radiofrequency ablation of spinal osteoid osteoma: A prospective study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017. 26: 313

3. Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Bandiera S, Amendola L, Van Urk P, Boriani S. Osteoid osteoma of the mobile spine: Surgical outcomes in 81 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011. 36: 2089-93

4. Hadjipavlou AG, Tzermiadianos MN, Kakavelakis KN, Lander P. Percutaneous core excision and radiofrequency thermo-coagulation for the ablation of osteoid osteoma of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2009. 18: 345

5. Kadhim M, Binitie O, O’Toole P, Grigoriou E, De Mattos CB, Dormans JP. Surgical resection of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma of the spine. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2017. 26: 362

6. Laus M, Albisinni U, Alfonso C, Zappoli FA. Osteoid osteoma of the cervical spine: Surgical treatment or percutaneous radiofrequency coagulation?. Eur Spine J. 2007. 16: 2078

7. Rehnitz C, Sprengel SD, Lehner B, Ludwig K, Omlor G, Merle C. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma: Clinical success and long-term follow up in 77 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2012. 81: 3426

8. Rybak LD, Gangi A, Buy X, La Rocca Vieira R, Wittig J. Thermal ablation of spinal osteoid osteomas close to neural elements: Technical considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010. 195: W293

9. Wang B, Han SB, Jiang L, Yuan HS, Liu C, Zhu B. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for spinal osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. Eur Spine J. 2017. 26: 1884

10. Fielding JW, Keim HA, Hawkins RJ, Gabrielian JC. Osteoid osteoma of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977. 128: 163-4

11. Amirjamshidi A, Roozbeh H, Sharifi G, Abdoli A, Abbassioun K. Osteoid osteoma of the first 2 cervical vertebrae. Report of 4 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010. 13: 707-14

12. Etemadifar MR, Hadi A. Clinical findings and results of surgical resection in 19 cases of spinal osteoid osteoma. Asian Spine J. 2015. 9: 386-93

13. Zou MX, Lv GH, Li J, Wang XB. Osteoid osteoma at the posterior element of lumbar spinal column in a young boy. Spine J. 2016. 16: e651-2

14. Nebreda CL, Vallejo R, Mayoral-Rojals V, Ojeda A. Osteoid osteoma: Benign osteoblastic tumor of the lumbar l4 transverse process associated with radicular pain: A case report. Pain Pract. 2018. 18: 118-22

15. Zhang H, Niu X, Wang B, He S, Hao D. Scoliosis secondary to lumbar osteoid osteoma: A case report of delayed diagnosis and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016. 95: e5362

16. Schaffer V, Wegener B, Dürr HR. Classical surgical resection of osteoid osteoma of the cervical spine. Acta Chir Belg. 2010. 110: 603-6