- Department of Endovascular Neurosurgery, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Hidaka, Japan

Correspondence Address:

Koki Onodera, Department of Endovascular Neurosurgery, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Hidaka, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_493_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Koki Onodera, Kuya Azekami, Noriyuki Yahagi, Ryutaro Kimura, Ryuta Kajimoto, Masataka Yoshimura, Shinya Kohyama. Spontaneous disappearance of a small unruptured cerebral aneurysm in the clinoid segment of the internal carotid artery: A case report and literature review. 23-Aug-2024;15:299

How to cite this URL: Koki Onodera, Kuya Azekami, Noriyuki Yahagi, Ryutaro Kimura, Ryuta Kajimoto, Masataka Yoshimura, Shinya Kohyama. Spontaneous disappearance of a small unruptured cerebral aneurysm in the clinoid segment of the internal carotid artery: A case report and literature review. 23-Aug-2024;15:299. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13055

Abstract

Background: Various degrees of thrombosis have been reported in patients with giant aneurysms. However, small, unruptured aneurysms rarely resolve spontaneously. Herein, we report a case of a small unruptured aneurysm in the clinoid segment (C3) of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) that showed almost complete occlusion at the 1-year follow-up.

Case Description: A 66-year-old woman developed a subarachnoid hemorrhage on the left side of the perimesencephalic cistern. Cerebral angiography performed on admission revealed no evidence of hemorrhage. Subsequent cerebral angiography on day 12 revealed a dissecting aneurysm on a branch of the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), and the patient underwent parental artery occlusion with 25% n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on day 22 with a modified Rankin Scale score of 1. The 1 year follow-up cerebral angiogram demonstrated that the dissecting aneurysm in the SCA branch remained occluded. Notably, a small 2-mm unruptured aneurysm in the clinoid segment (C3) of the left ICA, which was present at the onset of subarachnoid hemorrhage, was almost completely occluded without intervention. Magnetic resonance angiography 1 year after spontaneous resolution of the aneurysm showed no apparent recurrence.

Conclusion: This case highlights that even small, unruptured aneurysms can develop spontaneous occlusions.

Keywords: Small aneurysm, Spontaneous disappearance, Thrombosis, Unruptured cerebral aneurysm

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial aneurysms can partially or completely disappear on neuroimaging studies due to thrombosis.[

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old woman without a notable medical history was brought to her primary physician with a sudden onset of occipital pain while swimming. She was referred to our hospital after a computed tomography (CT) scan showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage on the left side of the perimesencephalic cistern [

Figure 1:

(a) Computed tomography scan on admission showing subarachnoid haemorrhage on the left side of the perimesencephalic cistern. (b) Three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography (3D-DSA) performed on admission showing a saccular aneurysm measuring 1.9 mm at the neck and 2 mm in depth in the left internal carotid artery (ICA). (c and d) 3D-DSA on day 12 before and after parent artery occlusion with 25% n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate performed for a dissecting aneurysm in the branch of the left superior cerebellar artery.

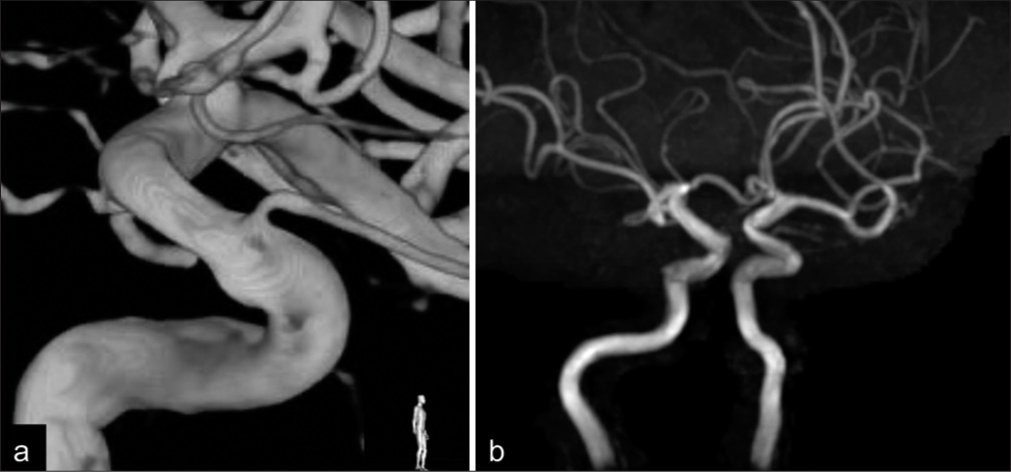

Figure 2:

(a) One year follow-up three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography showing spontaneous, almost complete occlusion of the Internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysm with a slight bulge remaining at its neck. (b) Magnetic resonance angiography one year after disappearance of the aneurysm showing no apparent recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous resolution of cerebral aneurysms is common in ruptured aneurysms,[

However, the spontaneous disappearance of small unruptured aneurysms is rare, and the underlying mechanism has not been clarified. Despite the lack of configuration features that predispose patients to thrombus formation, ischemic events have been reported in small unruptured saccular aneurysms, and distal clot embolization from the aneurysmal sac is the most common mechanism.[

The interval between the identification and disappearance of small aneurysms ranges from 1 to 15 years, and the degree of disappearance varies.[

Yamada et al. showed the spontaneous disappearance of small unruptured aneurysms in the clinoid segment of the ICA with intra-aneurysmal T2 high intensity, suggesting thrombosis.[

There is no consensus regarding the management of small thrombotic aneurysms. Vandenbulcke et al. reported that none of the 13 (0%) thrombotic aneurysms measuring <10 mm ruptured, although one of 6 (17%) measuring 10-20 mm and 2 (100%) larger than 20 mm thrombotic aneurysms ruptured, and that aneurysm size was the factor predicting rupture.[

In addition, Akimoto et al. reported a small unruptured aneurysm of the distal anterior cerebral artery that completely occluded spontaneously but recurred 2 years later,[

CONCLUSION

Here, we report the spontaneous disappearance of a small unruptured aneurysm in the clinoid segment of the ICA. The etiology of this phenomenon has not yet been elucidated. However, neuroimaging findings suggested that this may be related to thrombosis. Long-term follow-up is required due to the potential risk of recanalization and ischemic stroke, in addition to clarifying the etiology.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Akimoto Y, Yanaka K, Onuma K, Nakamura K, Takahashi N, Ishikawa E. Spontaneous disappearance of an intracranial small unruptured aneurysm on magnetic resonance angiography: Report of two cases. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020. 15: 1055-8

2. Allen LM, Fowler AM, Walker C, Derdeyn CP, Nguyen BV, Hasso AN. Retrospective review of cerebral mycotic aneurysms in 26 patients: Focus on treatment in strongly immunocompromised patients with a brief literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013. 34: 823-7

3. Baharoglu MI, Lauric A, Gao BL, Malek AM. Identification of a dichotomy in morphological predictors of rupture status between sidewall-and bifurcation-type intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2012. 116: 871-81

4. Begley SL, White TG, Khilji H, Katz J, Dehdashti AR. Disappearance of a small unruptured intracranial aneurysm: A case report and brief literature review. Neuroradiol J. 2023. 36: 621-4

5. Choi CY, Han SR, Yee GT, Lee CH. Spontaneous regression of an unruptured and non-giant intracranial aneurysm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012. 52: 243-5

6. Cohen JE, Gomori JM, Leker RR. Thrombosis of non-giant unruptured aneurysms causing ischemic stroke. Neurol Res. 2010. 32: 971-4

7. Cohen JE, Itshayek E, Gomori JM, Grigoriadis S, Raphaeli G, Spektor S. Spontaneous thrombosis of cerebral aneurysms presenting with ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2007. 254: 95-8

8. Kim HJ, Kim JH, Kim DR, Kang HI. Thrombosis and recanalization of small saccular cerebral aneurysm: Two case reports and a suggestion for possible mechanism. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014. 55: 280-3

9. Morón F, Benndorf G, Akpek S, Dempsy R, Strother CM. Spontaneous thrombosis of a traumatic posterior cerebral artery aneurysm in a child. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005. 26: 58-60

10. Nguyen HS, Doan N, Eckardt G, Gelsomino M, Shabani S, Brown WD. A completely thrombosed, nongiant middle cerebral artery aneurysm mimicking an intra-axial neoplasm. Surg Neurol Int. 2015. 6: 146

11. Ni W, Xu F, Xu B, Liao Y, Gu Y, Song D. Disappearance of aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease after STAMCA anastomosis with encephaloduro myosynangiosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2012. 19: 485-7

12. Otani T, Nakamura M, Fujinaka T, Hirata M, Kuroda J, Shibano K. Computational fluid dynamics of blood flow in coil-embolized aneurysms: Effect of packing density on flow stagnation in an idealized geometry. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2013. 51: 901-10

13. Redekop G, TerBrugge K, Montanera W, Willinsky R. Arterial aneurysms associated with cerebral arteriovenous malformations: Classification, incidence, and risk of hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1998. 89: 539-46

14. Ribeiro de Sousa D, Vallecilla C, Chodzynski K, Corredor Jerez R, Malaspinas O, Eker OF. Determination of a shear rate threshold for thrombus formation in intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016. 8: 853-8

15. Takemoto K, Tateshima S, Rastogi S, Gonzalez N, Jahan R, Duckwiler G. Disappearance of a small intracranial aneurysm as a result of vessel straightening and in-stent stenosis following use of an Enterprise vascular reconstruction device. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014. 6: e4

16. Vandenbulcke A, Messerer M, Starnoni D, Puccinelli F, Daniel RT, Cossu G. Complete spontaneous thrombosis in unruptured non-giant intracranial aneurysms: A case report and systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021. 200: 106319

17. Whittle IR, Dorsch NW, Besser M. Spontaneous thrombosis in giant intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982. 45: 1040-7

18. Yamada Y, Kinjo T, Ohki M, Kayama T. Spontaneous thrombosis of an unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysm: A case report. Surg Cereb Stroke. 2010. 38: 114-8

19. Yokoya S, Hino A, Oka H. Rare spontaneous disappearance of intracranial aneurysm. World Neurosurg. 2020. 134: 452-3

20. Zhang YS, Wang S, Wang Y, Tian ZB, Liu J, Wang K. Treatment for spontaneous intracranial dissecting aneurysms in childhood: A retrospective study of 26 cases. Front Neurol. 2016. 7: 224