- National Institute of Nursing Education, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

- Department of Neurosurgery, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Correspondence Address:

Sivashanmugam Dhandapani

Department of Neurosurgery, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.167084

Copyright: © 2015 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Dhandapani M, Gupta S, Dhandapani S, Kaur P, Samra K, Sharma K, Dolma K, Mohanty M, Singla N, Gupta SK. Study of factors determining caregiver burden among primary caregivers of patients with intracranial tumors. Surg Neurol Int 09-Oct-2015;6:160

How to cite this URL: Dhandapani M, Gupta S, Dhandapani S, Kaur P, Samra K, Sharma K, Dolma K, Mohanty M, Singla N, Gupta SK. Study of factors determining caregiver burden among primary caregivers of patients with intracranial tumors. Surg Neurol Int 09-Oct-2015;6:160. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/study-of-factors-determining-caregiver-burden-among-primary/

Abstract

Background:Caregivers of patients with intracranial tumors handle physical, cognitive, and behavioral impairments of patients. The purpose of this study was to assess the magnitude of burden experienced by primary caregivers of patients operated for intracranial tumors and evaluate factors influencing it.

Methods:Descriptive cross-sectional design was used to assess home-care burden experienced by primary caregivers of patients operated for intracranial tumors. Using purposive sampling, 70 patient-caregiver pairs were enrolled. Modified caregiver strain index (MCSI) was used to assess the caregiver burden. Mini mental status examination (MMSE), Katz index of independence in activities of daily living (ADL), and neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q) were used to assess the status of patients.

Results:Of 70 caregivers, 45 had mild, and 22 had moderate MCSI burden. A number of behavioral changes in NPI-Q had a significant correlation with MCSI burden (P P = 0.004) among behavioral changes of patients and caregivers’ inability to meet household needs (P

Conclusions:Behavioral changes in patients (especially irritability) and financial constraints had a significant independent impact on the burden experienced by primary caregivers of patients operated for intracranial tumors. Identifying and managing, these are essential for reducing caregiver burden.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, intracranial tumors, Katz activities of daily living, mini mental status examination, modified caregiver strain index, neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare has seen burgeoning of research into the area of family caregiving during the past three decades, as it became evident that caregivers of patients with long-term illnesses go through physical and psychological challenges resulting in poor quality of life (QoL).[

However, the independent impact of various factors contributing to caregiver burden has not been studied using multivariate model. The aim of this study was to assess the caregiver burden experienced by the primary caregivers of patients operated for intracranial tumor and assess the independent impact of various factors influencing it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on patients and caregivers attending Department of Neurosurgery, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, a tertiary level healthcare and research institute in North India. All the adult primary caregivers who stay with the patient at home and involved in direct care of adult intracranial tumor patients were identified and invited for written consent. Caregivers with any communication disability were excluded. The study was explained to 78 caregivers who attended the Outpatient Department during the study period, but a sample of 70 patient-caregiver pairs were involved in this study. The subjects were explained regarding objectives and duration of the study. The subjects were ensured confidentiality of information provided by them. The main reason for not participating was a lack of time. Written permission for conducting the research study reported by caregivers was obtained from Institute Ethics Committee.

Instruments

Modified caregiver strain index (MCSI), a tool with a high internal reliability (0.9) which quickly identifies the caregiver strain,[

Neuropsychiatric behavioral changes in patients were assessed using neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q) which identifies 12 behavioral disturbances occurring in patients such as delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability, apathy, motor activity, sleep disturbance, and appetite disorder. Information about the behavior is obtained from the primary caregiver who is familiar with the patient's behavior. The interview was conducted in the absence of the patient to obtain an accurate report on patient behavior. NPI-Q is reported to have high reliability, sensitivity, and validity in cross cultural studies.[

Mini mental status examination (MMSE) was used to assess the cognitive status of patients. It examines functions including registration, attention and calculation, recall, language, ability to follow simple commands, and orientation. It is a widely used cognitive test with high reliability, and validity of 0.70–0.90.[

Katz index of independence in activities of daily living (ADL) was used to assess the functional status and independence of patients. The Katz ADL index has good reliability and concurrent validity.[

Procedure of data collection

The caregivers were explained about the self-report MCSI and asked to give their honest option for each item in the questionnaire. Patient's cognitive status was assessed using MMSE and their functional status was assessed using Katz ADL. Behavioral changes of patients were reported by caregivers based on the items given in NPI-Q. A pilot study was done on 10 subjects to assess feasibility and applicability of the tools.

Data analysis

Continuous variables were considered nonparametric and reported as median with inter quartile range (IQR). Categorical data were reported as counts and proportions in each group. SPSS21 software (IBM Corp., New York, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Univariate analyses of continuous variables across binary categories were compared using Mann–Whitney U-test, and across multiple categories using Kruskal–Wallis test. The bivariate relationships between two continuous variables were assessed using Spearman correlation coefficient. The significance level was kept at P < 0.05. Only those factors impacting MCSI in univariate analyses with P < 0.20 were considered for multivariate analysis. General linear model was used for multivariate analysis with the mandatory significance of model coefficient to be <0.05 for the validity of outcome prediction.

RESULTS

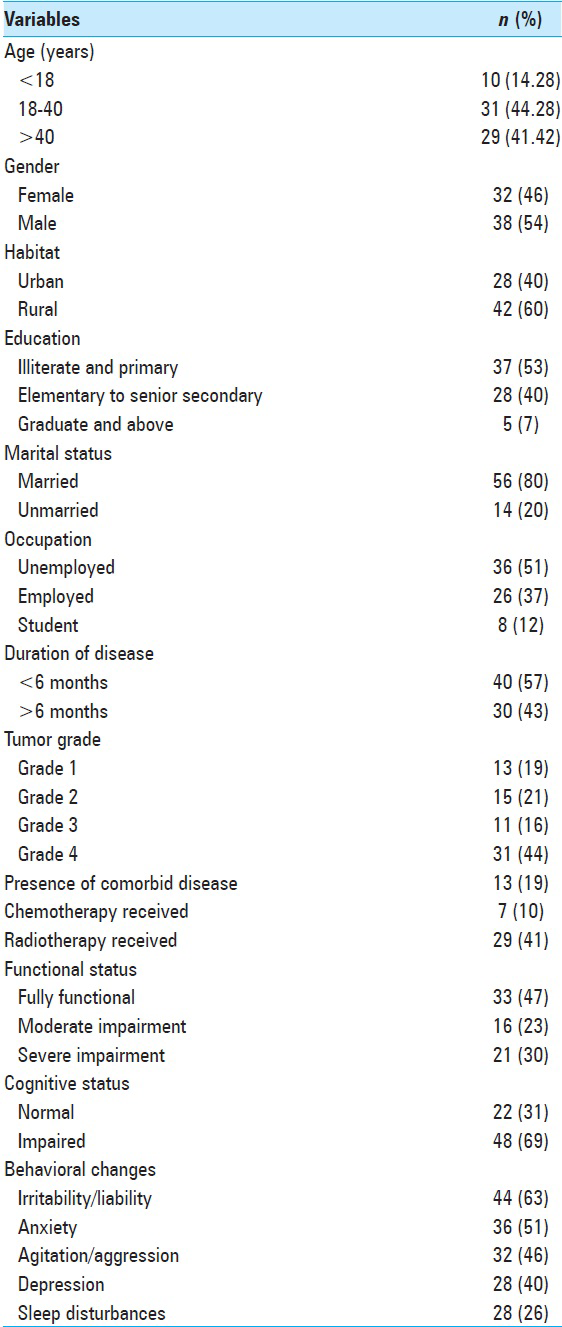

The profiles of patients and caregivers are depicted in Tables

The mean age of patients was 40.2 (±1.48) years with a male:female ratio of 1.2:1. Of the total 70 patients, most (44%) had tumors which were Grade 4. As per MMSE, 69% of the patients had various degrees of cognitive impairments. On behavioral assessment with NPI-Q, 63% of patients were noted to have irritability/lability, 51% anxiety, 46% agitation/aggression, 40% depression/dysphoria, 28% disturbed night time behavior, and 24% with change in appetite [

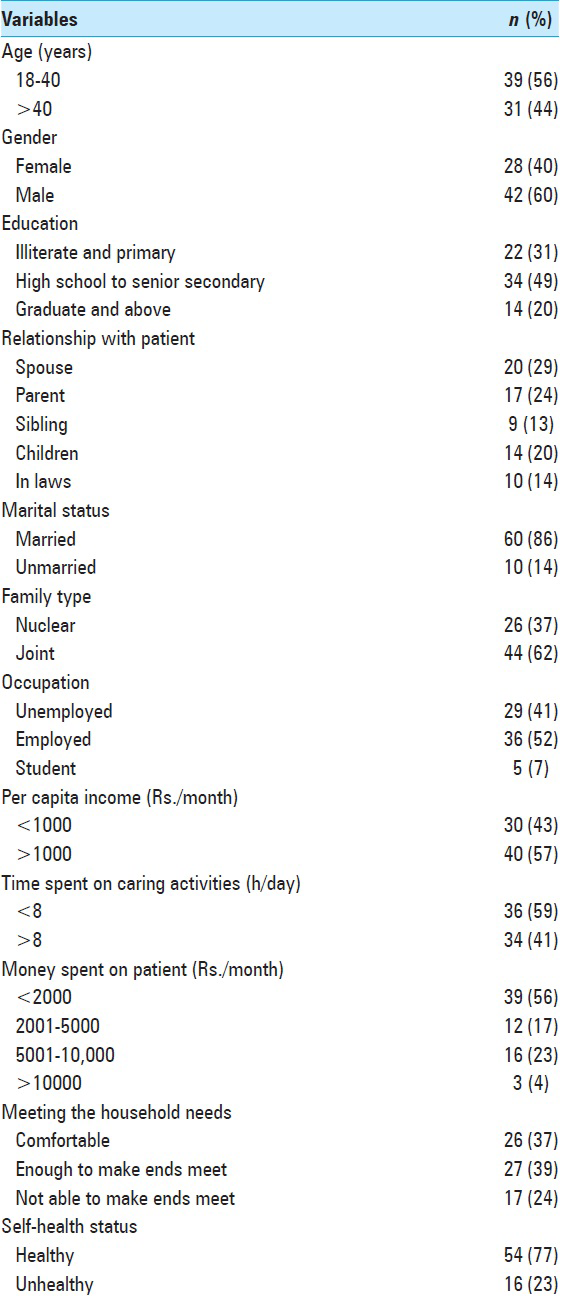

The caregivers of patients were in the age ranging from 18 to 78 years with a mean of 37.3 (±9.88) years [

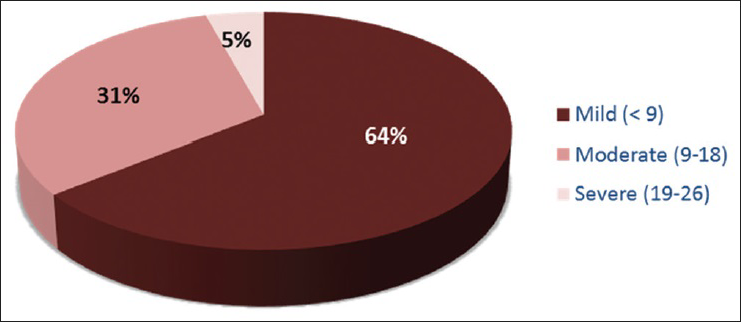

Caregiver burden

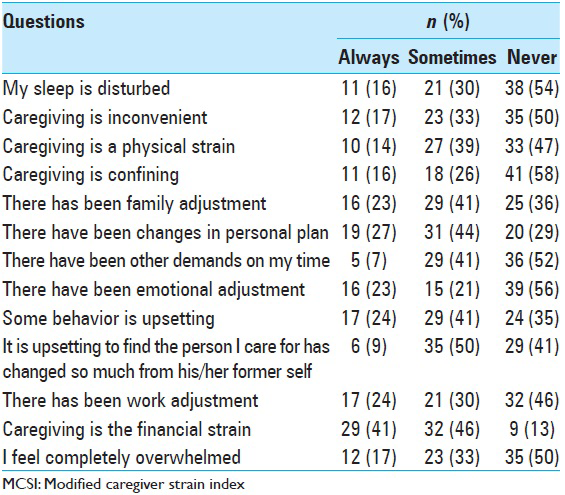

As per MCSI self-reported data, all caregivers had some degree of burden. About 64% of the caregivers were found to have mild burden, 31% with moderate burden, and 5% having severe burden [

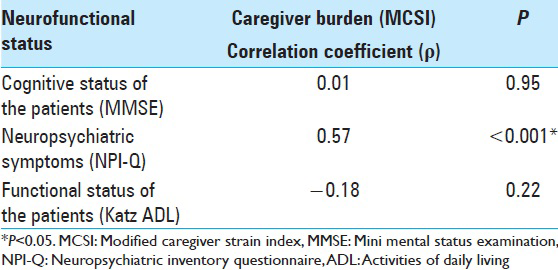

As shown in

Impact of patient related factors on caregiver burden

As shown in

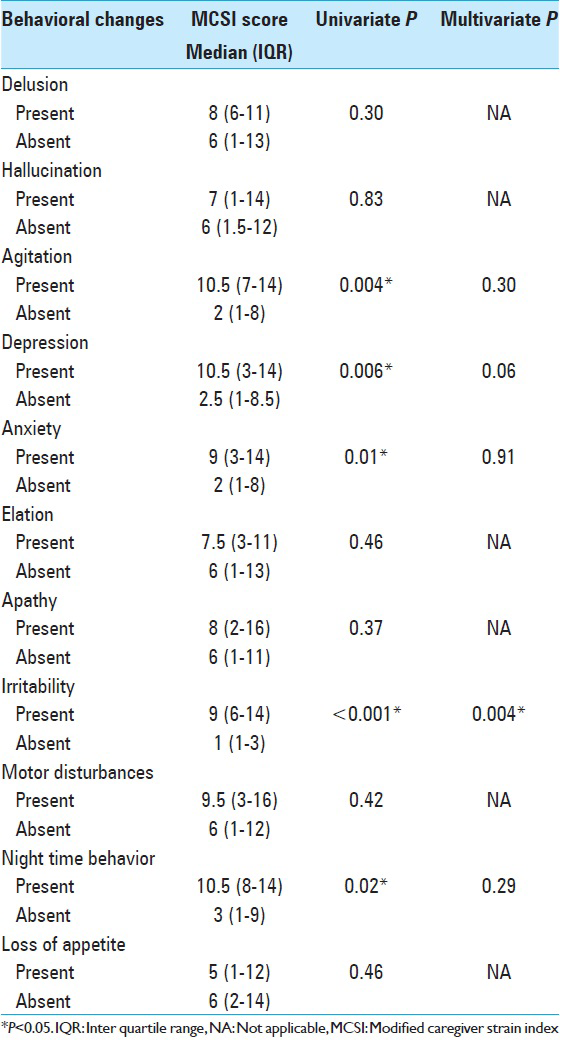

The impact of neuropsychiatric behavioral changes of patients on caregiver burden is represented in

Impact of caregiver related factors on caregiver burden

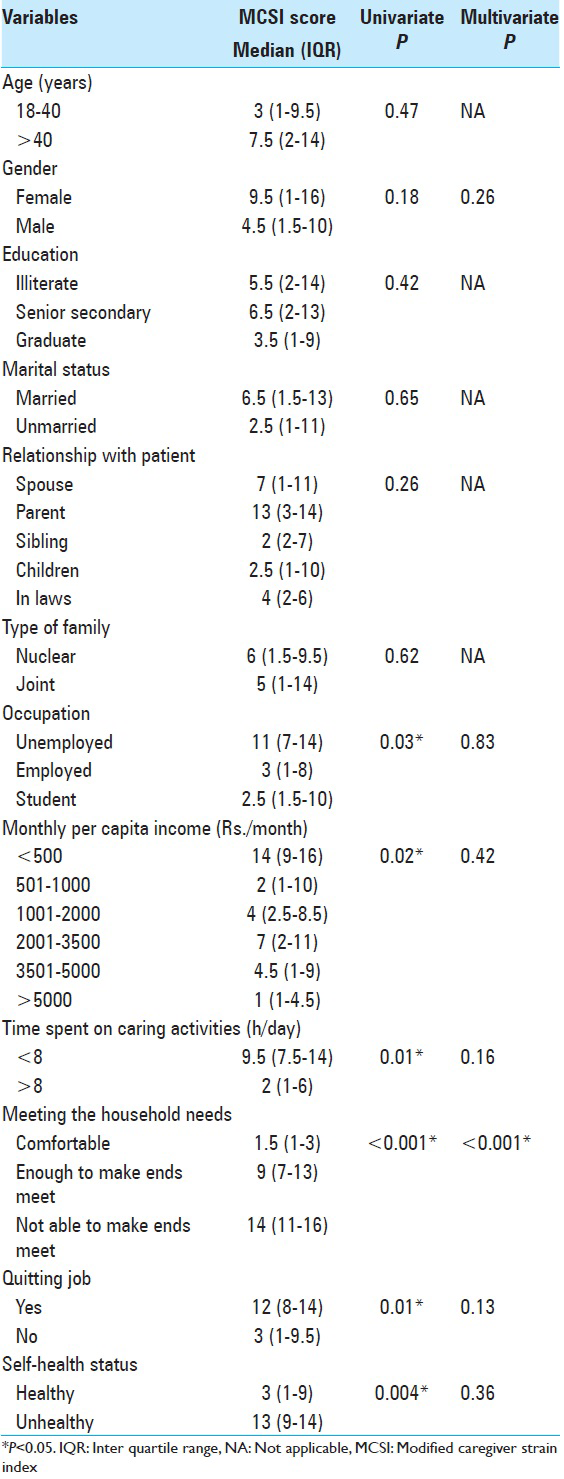

As shown in

DISCUSSION

The functional, cognitive, and neuropsychological changes of patients with intracranial tumors make their primary caregivers exposed to a great burden[

Most of the patients (68%) in our study had high grade glioma followed by meningioma, as per their reported prevalence.[

Cognitive and functional impairments along with neuropsychological changes faced by patients of intracranial tumors are well evident. In the present study, 64% of patients were found to have cognitive impairments. We could not find any significant association of cognitive impairments with caregiver burden while they have been reported to influence caregiver stress in other caregiving populations.[

The neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients in our study had a significant impact on caregiver burden. About 82% of patients reported one or more behavioral changes in NPI. There was a significant positive correlation between the number of symptoms in NPI-Q and the caregiver burden. Caregivers experienced significantly more burden when the patient had behavioral changes such as agitation, depression, irritability, and disturbed night time behavior. These behavioral changes in patients probably demand more time and effort from the caregiver to fulfill even their basic needs. Patients who are irritable and agitated are difficult to be convinced to do any activities because of their rebellious nature.[

The present study has highlighted the association between caregivers’ socioeconomic profile and caregiver burden. The monthly expenditure for treatment related issues was considerably higher as compared to their monthly per capita income. It was noted that caregivers who were unemployed and those who had quit their job to look after their patients had reported significantly more burden. Unemployment adds to the financial and emotional burden of low income and makes it difficult for them to meet even their basic household needs. Caregivers with lower income and those who were not able to make their ends meet had significantly higher level of burden. Lower socioeconomic status has been reported to influence caregiver burden in many illnesses thereby impacting the outcome.[

A significantly higher burden score was reported by caregivers who could spend only short time in caregiving. This might be due to their employment or poor health status. Managing caregiving along with job and household activities would add to their stress. Caregivers who reported themselves unhealthy also had the higher burden. Higher burden score was found when the caregivers were parents of patients. Other demographic factors of the caregivers such as age, gender, education, marital status, and type of family were found to have no significant influence on the care burden in this study.

The significant independent impact of irritability (P = 0.004) of patients and financial constraints of caregivers (P < 0.001), with the caregiver burden noted in multivariate analyses, have never been reported previously. These highlights are a profound need for managing behavioral symptoms in patients and financial support for caregivers more effectively.

This evidence on caregiver burden suggests the importance of formal caregiver empowerment programs and support groups to improve the quality of caregiving as well as the life of the caregivers.[

Merits and limitations

Caregivers and patients were directly interviewed in our study with the help of appropriate standard tools while other reported studies had telephonic interviews. Futhermore, the cognitive status of patients was assessed directly rather than relying on caregivers’ perception. We assessed independent impact of various factors using multivariate analysis while previous studies had relied on univariate analysis. The subjective elements experienced by primary caregivers such as spiritual perceptions and support from other family members were not feasible to be evaluated objectively in our study. We also did not study the tolerance threshold and personality of caregivers.

CONCLUSION

Within the caregiving dyad, the burden is related to characteristics of both the caregivers and patients. Behavioral changes in patients (especially irritability) and financial constraints had a significant independent impact on caregiver burden. Hence, managing behavioral changes of these patients and empowering their caregivers are essential in overall health delivery. With better management of patients’ behavioral changes and providing social support to the caregivers, we could definitely bring some ray of hope.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Arber A, Faithfull S, Plaskota M, Lucas C, de Vries K. A study of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour and their carers: Symptoms and access to services. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010. 16: 24-30

2. Arber A, Hutson N, Guerrero D, Wilson S, Lucas C, Faithfull S. Carers of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour: Are their information needs being met?. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2010. 6: 329-34

3. Baillieux H, De Smet HJ, Lesage G, Paquier P, De Deyn PP, Mariën P. Neurobehavioral alterations in an adolescent following posterior fossa tumor resection. Cerebellum. 2006. 5: 289-95

4. Boele FW, Heimans JJ, Aaronson NK, Taphoorn MJ, Postma TJ, Reijneveld JC. Health-related quality of life of significant others of patients with malignant CNS versus non-CNS tumors: A comparative study. J Neurooncol. 2013. 115: 87-94

5. Bradley S, Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Hamilton R, Rosenzweig M, Hricik A. I could lose everything: Understanding the cost of a brain tumor. J Neurooncol. 2007. 85: 329-38

6. Butler JM, Rapp SR, Shaw EG. Managing the cognitive effects of brain tumor radiation therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006. 7: 517-23

7. Cornwell P, Dicks B, Fleming J, Haines TP, Olson S. Care and support needs of patients and carers early post-discharge following treatment for non-malignant brain tumour: Establishing a new reality. Support Care Cancer. 2012. 20: 2595-610

8. Correa DD, Shi W, Thaler HT, Cheung AM, DeAngelis LM, Abrey LE. Longitudinal cognitive follow-up in low grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2008. 86: 321-7

9. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994. 44: 2308-14

10. De Smet HJ, Baillieux H, Wackenier P, De Praeter M, Engelborghs S, Paquier PF. Long-term cognitive deficits following posterior fossa tumor resection: A neuropsychological and functional neuroimaging follow-up study. Neuropsychology. 2009. 23: 694-704

11. Dhandapani SS, Manju D, Mahapatra AK. The economic divide in outcome following severe head injury. Asian J Neurosurg. 2012. 7: 17-20

12. Dhandapani S, Sharma K. Is “en-bloc” excision, an option for select large vascular meningiomas?. Surg Neurol Int. 2013. 4: 102-

13. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975. 12: 189-98

14. Fox S, Lantz C. The brain tumor experience and quality of life: A qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1998. 30: 245-52

15. Goodman S, Rabow M, Folkman S.editors. Orientation to Caregiving – A Handbook for Family Caregivers of Patients with Brain Tumors. San Francisco: UCSF Neuro-Oncology Gordon Murray Caregiver Program and Osher Center for Integrative Medicine University of California; 2013. p.

16. Hricik A, Donovan H, Bradley SE, Given BA, Bender CM, Newberry A. Changes in caregiver perceptions over time in response to providing care for a loved one with a primary malignant brain tumor. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011. 38: 149-55

17. Janda M, Steginga S, Dunn J, Langbecker D, Walker D, Eakin E. Unmet supportive care needs and interest in services among patients with a brain tumour and their carers. Patient Educ Couns. 2008. 71: 251-8

18. Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients – Observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006. 14: 1258-61

19. Manoharan N, Julka PK, Rath GK. Descriptive epidemiology of primary brain and CNS tumors in Delhi, 2003-2007. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012. 13: 637-40

20. Mezue WC, Draper P, Watson R, Mathew BG. Caring for patients with brain tumor: The patient and care giver perspectives. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011. 14: 368-72

21. Parvataneni R, Polley MY, Freeman T, Lamborn K, Prados M, Butowski N. Identifying the needs of brain tumor patients and their caregivers. J Neurooncol. 2011. 104: 737-44

22. Pawl JD, Lee SY, Clark PC, Sherwood PR. Sleep characteristics of family caregivers of individuals with a primary malignant brain tumor. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013. 40: 171-9

23. Petruzzi A, Finocchiaro CY, Lamperti E, Salmaggi A. Living with a brain tumor: Reaction profiles in patients and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2013. 21: 1105-11

24. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: A meta-analytic comparison. Aging Ment Health. 2004. 8: 438-49

25. Schmer C, Ward-Smith P, Latham S, Salacz M. When a family member has a malignant brain tumor: The caregiver perspective. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008. 40: 78-84

26. Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: Family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro Oncol. 2008. 10: 61-72

27. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Doorenbos AZ, Given CW. Forgotten voices: Lessons from bereaved caregivers of persons with a brain tumour. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004. 10: 67-75

28. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Schiffman RF, Murman DL, Lovely M. Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Res Nurs Health. 2006. 29: 105-20

29. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Schiffman RF, Murman DL, von Eye A. The influence of caregiver mastery on depressive symptoms. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007. 39: 249-55

30. Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the reliability of the modified caregiver strain index. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003. 58: S127-32

31. Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: A comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992. 40: 922-35

32. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. Katz index of independence in activities of daily living (ADL). Urol Nurs. 2007. 27: 93-4

33. Wasner M, Paal P, Borasio GD. Psychosocial care for the caregivers of primary malignant brain tumor patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2013. 9: 74-95

34. Whisenant M. Informal caregiving in patients with brain tumors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011. 38: E373-81

35. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980. 20: 649-55