- Department of Neurological Surgery, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Urayasu, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Satoshi Tsutsumi, Department of Neurological Surgery, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Urayasu, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_440_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Satoshi Tsutsumi, Kiyotaka Kuroda, Hiroki Sugiyama, Natsuki Sugiyama, Hideaki Ueno, Hisato Ishii. Subsequent bilateral intracerebral hemorrhages in the putamen and thalamus: A report of four cases. 02-Sep-2022;13:403

How to cite this URL: Satoshi Tsutsumi, Kiyotaka Kuroda, Hiroki Sugiyama, Natsuki Sugiyama, Hideaki Ueno, Hisato Ishii. Subsequent bilateral intracerebral hemorrhages in the putamen and thalamus: A report of four cases. 02-Sep-2022;13:403. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11839/

Abstract

Background: Subsequent bilateral intracerebral hemorrhage (SBICH) in the putamen and thalamus is a rare condition. Herein, we report four such cases.

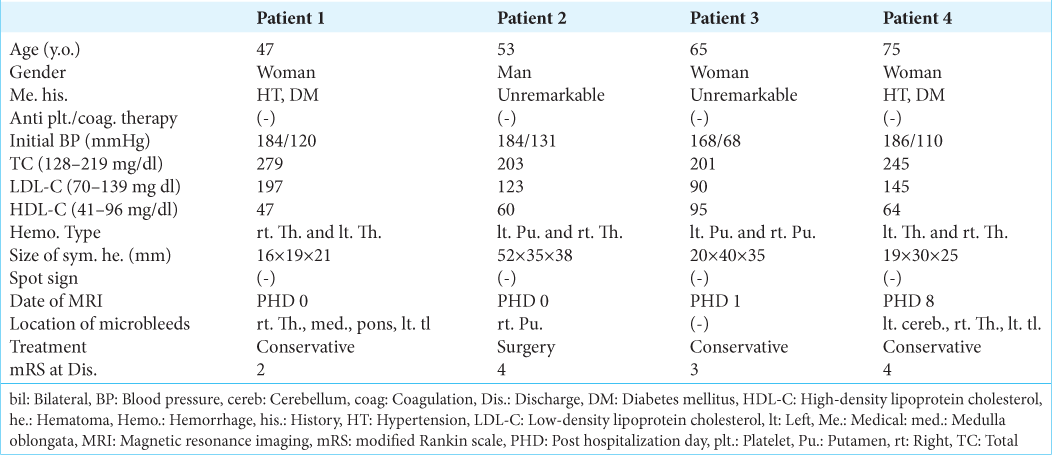

Case Description: Case 1: A 47-year-old woman presented with the left hemiparesis and elevated blood pressure. Neuroimaging revealed a right thalamic hemorrhage and a small left thalamic hemorrhage accompanying the hyperdense rim on computed tomography (CT) and the hypointense rim on gradient-echo T2*-weighted imaging (T2*WI). Case 2: A 53-year-old man presented with a disturbance of consciousness and elevated blood pressure. Neuroimaging revealed a left putaminal hemorrhage and a small right thalamic hemorrhage that appeared hyperdense on CT and hypointense on T2*WI. Case 3: A 65-year-old woman presented with the right hemiparesis and elevated blood pressure. Neuroimaging revealed a left putaminal hemorrhage and a small right thalamic hemorrhage accompanied by a hyperdense rim on CT and a hypointense rim on T2*WI. Case 4: A 75-year-old woman presented with the right hemiparesis and elevated blood pressure. Neuroimaging revealed a left thalamic hemorrhage and small hemorrhages in the right thalamus and cerebellar hemisphere. These hemorrhages appeared hyperdense on CT and hypointense on T2*WI.

Conclusion: SBICHs are rare bilateral hemorrhages that may present with asymptomatic microbleeds in the putamen or thalamus coupled with symptomatic, subsequent hemorrhages in the contralateral counterparts. The latter hemorrhage may develop during the subacute phase of microbleeds in the putamen or thalamus.

Keywords: Bilateral hemorrhages, Microbleeds, Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, Subsequent

INTRODUCTION

Despite the recognition of the benefits of a healthy lifestyle and the advantages of preventive medicine, spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) remains a dismal disease. It is estimated to develop at a mean rate of 26 out of 100,000 in the general population per year. Approximately half of ICH patients survive for 1 year, and nearly, two-fifths survive for 5 years.[

Simultaneous or subsequent bilateral ICHs are distinct entities that typically result in worse outcomes than solitary hemorrhages. They have been most frequently reported as bilateral putaminal or thalamic hemorrhages.[

Cerebral microbleeds, typically asymptomatic hemosiderin deposits found in the basal ganglia and thalamus, have been reported to show dynamic temporal changes. They are associated with large ICHs and significant volumes of white matter hyperintensities.[

Here, we report four cases of SBICHs that developed in the putamen and thalamus.

In this study, SBICHs were defined as a combination of asymptomatic, older hemorrhages in the unilateral putamen or thalamus, and younger hemorrhages in the contralateral counterparts that caused stroke. These hemorrhages appeared at least partially hyperdense on computed tomography (CT) and hypointense on gradient-echo T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T2*WI), In addition, microbleeds were determined to be hemorrhages smaller than 10 mm that appeared iso- or hypodense on CT, accompanied by dense hemosiderin depositions that were assessed on T2*WI.

CASE PRESENTATION

Between February 2017 and February 2022, 386 patients with spontaneous ICHs were admitted to the authors’ hospital. Among these patients, 4 (1.0%) were diagnosed with SBICHs. These four patients are described as follows:

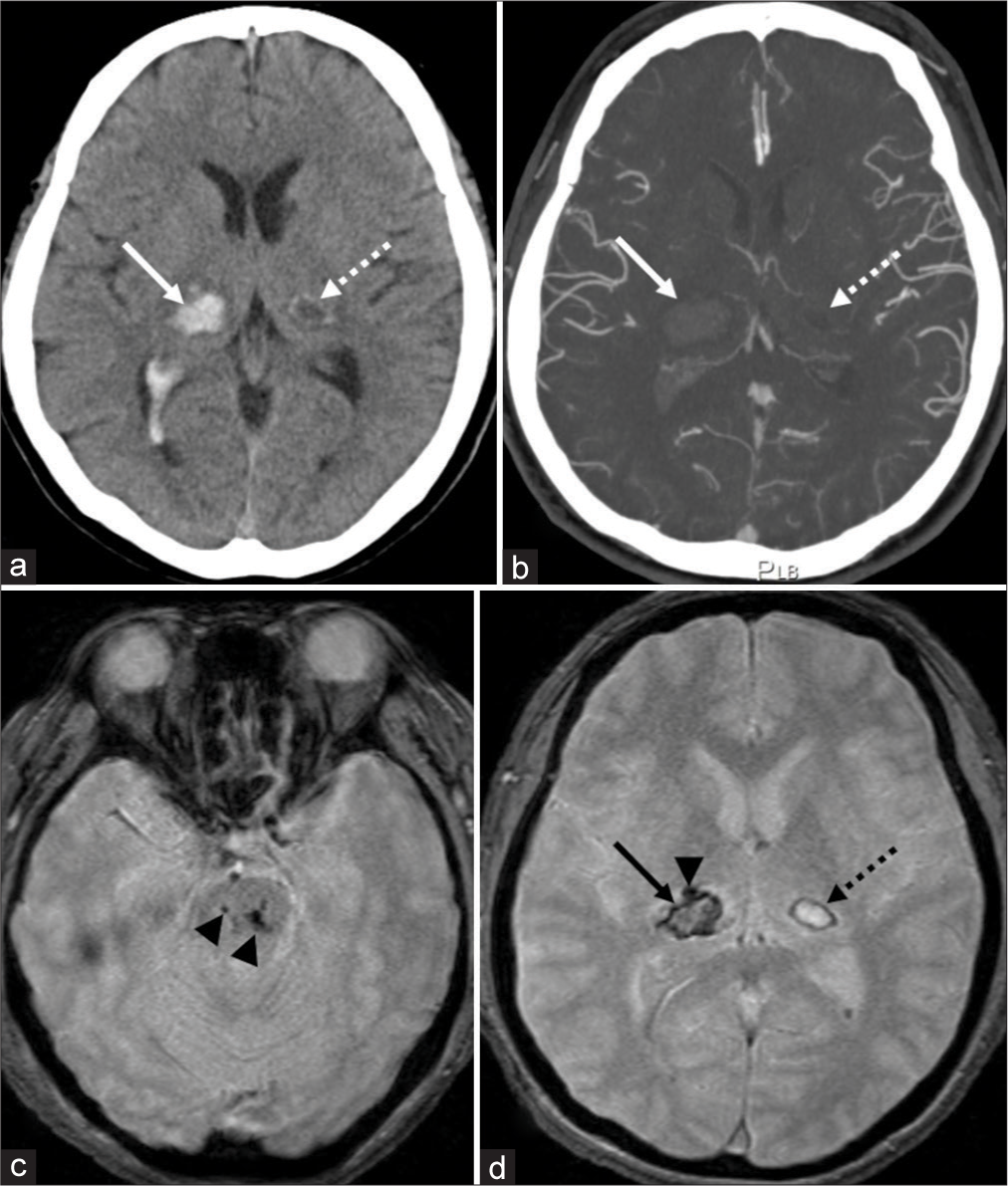

Case 1: A 47-year-old fully dependent woman presented with the left hemiparesis on awakening in the morning. The patient had a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperuremia. However, she had not been prescribed anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. Initially, her blood pressure was 184/120 mmHg. Serum TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C levels were 279 mg/dl (128–219), 197 mg/dl (70–139), and 47 mg/dl (41–96), respectively. CT and T2*WI images at presentation revealed a right thalamic hemorrhage, 16 mm × 19 mm × 21 mm in maximal dimension with ventricular perforation. In addition, a small, older hematoma, 10 mm × 5 mm in size, was identified in the left thalamus. “It was accompanied by a hyperdense rim on CT [

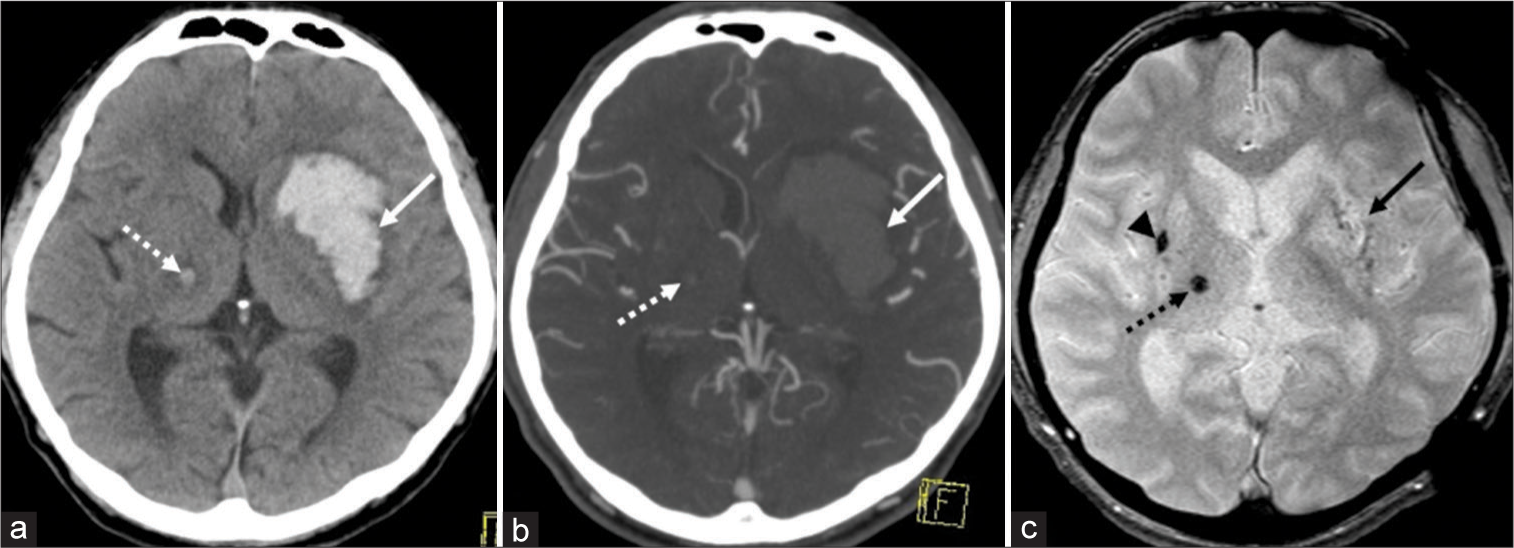

Case 2: A 53-year-old fully dependent man presented with a disturbance in consciousness that measured nine points on the Glasgow Coma Scale. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs had not been prescribed. Initially, this patient’s blood pressure was 184/131 mmHg. Serum levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were 203 mg/dl, 123 mg/dl, and 60 mg/dl, respectively. CT and T2*WI images at presentation revealed a large left putaminal hemorrhage, 52 mm × 35 mm × 38 mm in dimension. A small and older hematoma, 5 × 5 mm in dimension, was identified in the right thalamus with perilesional brain edema. This older hematoma appeared hyperdense on CT [

Figure 1:

Noncontrast (a) and postcontrast (b) axial computed tomography (CT) show a right thalamic hemorrhage, 16 mm × 19 mm × 21 mm in maximal dimension with ventricular perforation (arrow). On axial gradient-echo T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T2*WI), microbleeds are identified in the pons (c, arrowheads) and right thalamus (d, arrowhead), ventral to the thalamic hemorrhage (d, arrow). In addition, a small hematoma, 10 mm × 5 mm in dimension, is identified in the left thalamus. It accompanies hyperdense rim on CT that appears as a hypointense rim on T2*WI (a and d, dashed arrow). Postcontrast axial CT does not find spot signs (b, arrow and dashed arrow).

Figure 2:

Noncontrast axial computed tomography (CT) shows a left putaminal hemorrhage, 52 mm × 35 mm × 38 mm in dimension (a, arrow). Postcontrast axial CT does not detect spot signs (b, arrow and dashed arrow). On axial T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T2*WI), most of the putaminal hemorrhage appears isointense (c, arrow). In addition, a small hematoma, 5 mm × 5 mm in dimension, is identified in the right thalamus with perilesional brain edema. It appears hyperdense on CT, while hypointense on axial T2*WI (a and c, dashed arrow). A microbleed is identified in the right putamen (c, arrowhead).

Case 3: A 65-year-old fully dependent woman presented with the right hemiparesis. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable.

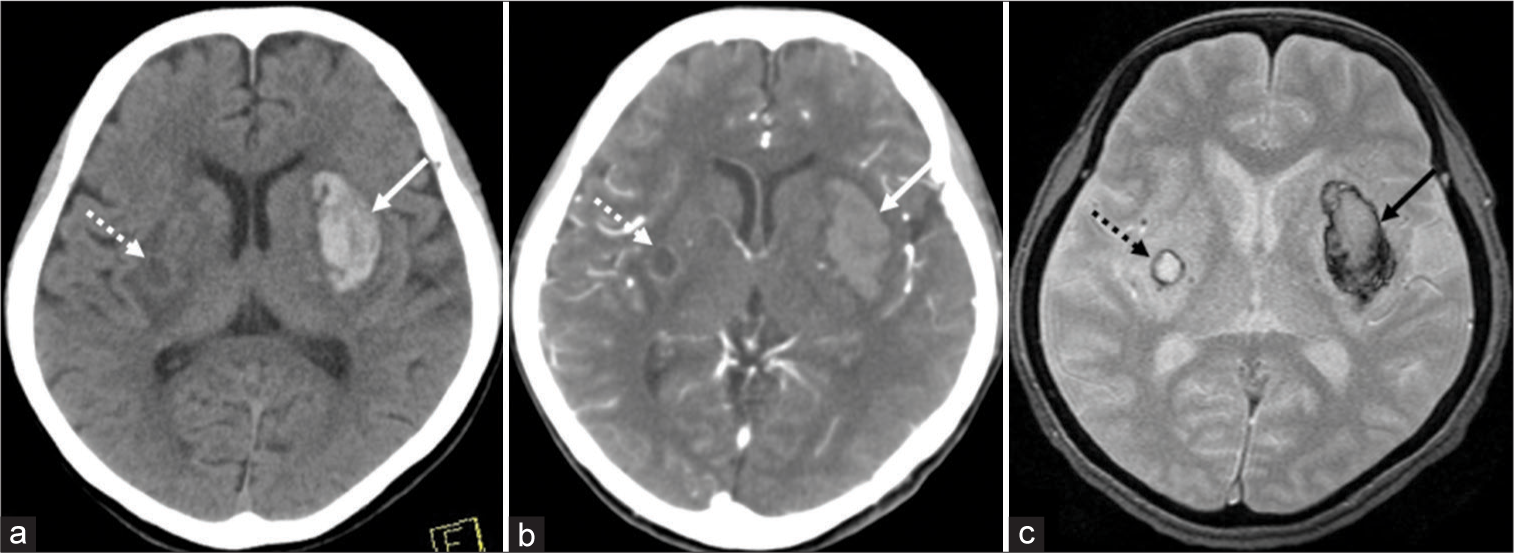

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs had not been prescribed. At presentation, her blood pressure was 168/68 mmHg. Serum levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were 201 mg/dl, 90 mg/dl, and 95 mg/dl, respectively. CT at presentation and T2*WI that were performed on posthospitalization day (PHD) 1 revealed a left putaminal hemorrhage, 20 mm × 40 mm × 35 mm in dimension. In addition, a small, older hematoma, 8 × 8 mm in dimension, was identified in the right putamen with perilesional brain edema. This older hematoma was accompanied by a hyperdense rim on CT [

Figure 3:

Noncontrast axial computed tomography (CT) shows a left putaminal hemorrhage, 20 mm × 40 mm × 35 mm in dimension (a, arrow). Postcontrast axial CT does not detect spot signs (b, arrow and dashed arrow). On axial T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T2*WI), the putaminal hemorrhage appears hypointense in the peripheral parts (c, arrow). In addition, a small hematoma, 8 mm × 8 mm in dimension, is identified in the right putamen with perilesional brain edema. It accompanies a hyperdense rim on CT that appears hypointense rim on axial T2*WI (a and c, dashed arrow).

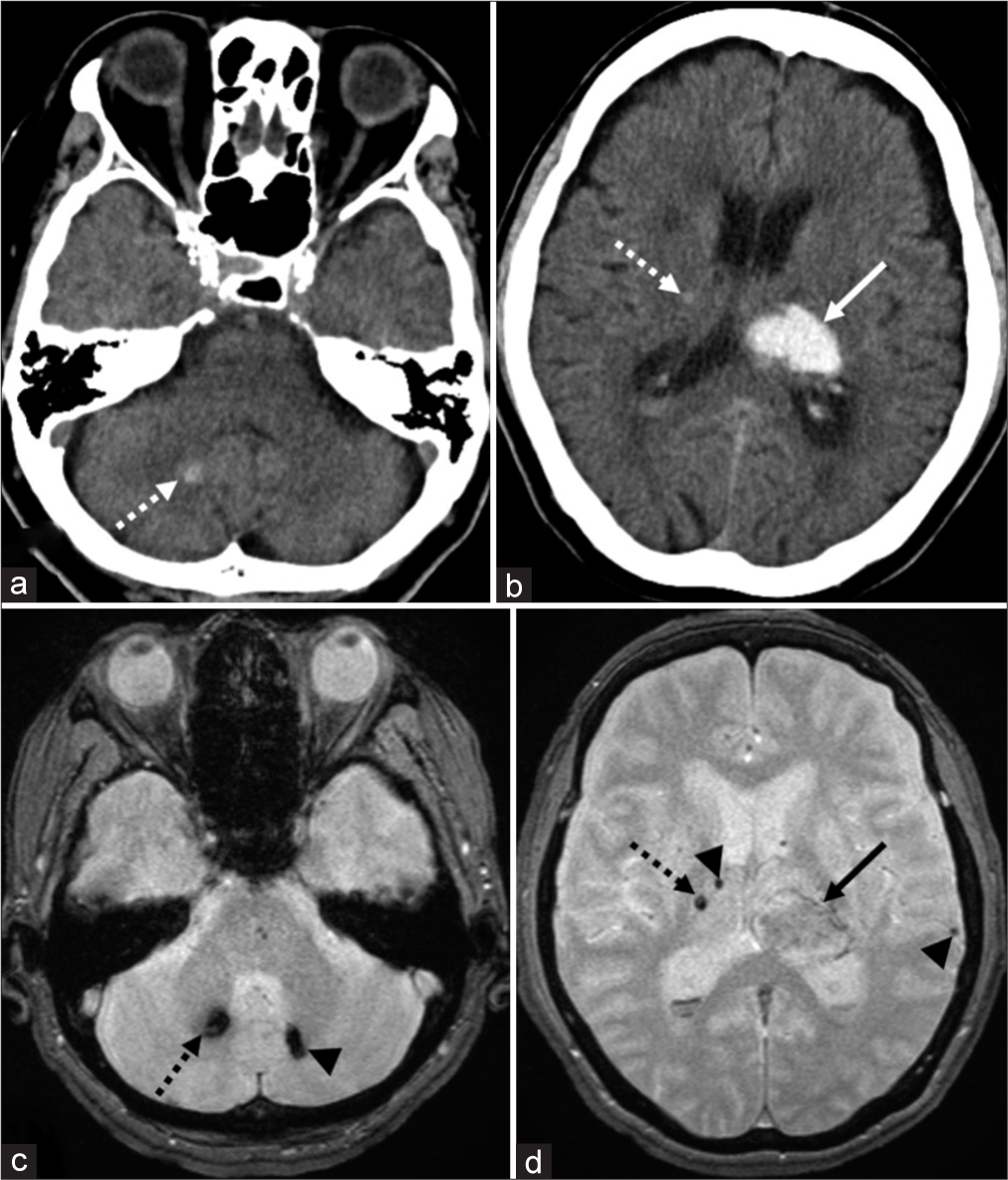

Case 4: A 75-year-old fully dependent woman presented with the right hemiparesis. The patient had a medical history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. She had not been prescribed anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. Initially, her blood pressure was 186/110 mmHg. Serum levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C were 245 mg/dl, 145 mg/dl, and 64 mg/dl, respectively. CT at presentation and T2*WI that were performed on PHD 8 revealed a left thalamic hemorrhage, 19 mm × 30 mm × 25 mm in dimension. In addition, small, older hematomas, 2 and 8 mm in dimension, were identified in the right thalamus and cerebellar hemisphere, respectively. These hematomas appeared hyperdense on CT and hypointense on T2*WI [

Figure 4:

Noncontrast axial computed tomography (CT) shows a left thalamic hemorrhage, 19 mm × 30 mm × 25 mm in dimension, in addition to small hematomas, 2 and 8 mm in dimensions in the right thalamus and right cerebellar hemisphere, respectively (a and b, dashed arrow; b, arrow). The small hematomas appear hyperdense on CT, while hypointense on T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T2*WI) (a-d, dashed arrow). On axial T2*WI, most of the left thalamic hemorrhage appears isointense (d, arrow). In addition, other microbleeds are identified in the right thalamus, left cerebellar hemisphere, and left temporal lobe (c and d, arrowhead).

DISCUSSION

In our four patients, SBICHs in the putamen and thalamus presented as a combination of asymptomatic, small ICH in the subacute phase, and contralateral ICH that occurred stroke. Initially, these patients exhibited an elevated blood pressure at mean of 180.5 ± 7.3/107.3 ± 23.8 mmHg. This suggested that hypertension may be an associated factor of the SBICHs. In addition, all the small ICHs were asymptomatic and <10 mm in diameter. They were cystic in Cases 1 and 3 and solid hematomas in Cases 2 and 4. The various consistencies may reflect dynamic temporal changes of microbleeds.[

Microbleeds are thought to be associated with serum levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C. The previous studies have suggested that a low level of TC and HDL-C may be associated with an increase of microbleeds in the deep cerebral hemisphere, while a high level of LDL-C may act as a protective factor against increased microbleeds.[

CONCLUSION

SBICHs are rare bilateral hemorrhages that may present with asymptomatic microbleeds in the putamen or thalamus coupled with symptomatic, subsequent hemorrhages in the contralateral counterparts. The latter hemorrhage may develop during the subacute phase of microbleeds in the putamen or thalamus.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Balestrieri A, Lucatelli P, Suri HS, Montisci R, Suri JS, Wintermark M. Volume of white matter hyperintensities, and cerebral micro-bleeds. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021. 30: 105905

2. Choudhary A, Goyal MK, Singh R. Simultaneous bilateral hypertensive thalamic hemorrhage: A rare event. Neurol India. 2018. 66: 575-7

3. Dromerick AW, Meschia JF, Kumar A, Hanlon RE. Simultaneous bilateral thalamic hemorrhages following the administration of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997. 78: 92-4

4. Gotoh S, Hata J, Nomiyama T, Hirakawa Y, Nagata M, Mukai N. Trends in the incidence and survival of intracerebral hemorrhage by its location in a Japanese community. Circ J. 2014. 78: 403-9

5. Han JH, Jeon JP, Choi HJ, Yang JS, Kang SH, Cho YJ. Delayed consecutive contralateral thalamic hemorrhage after spontaneous thalamic hemorrhage. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2016. 18: 106-9

6. Imai K. Bilateral simultaneous thalamic hemorrhages--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2000. 40: 369-71

7. Kabuto M, Kubota T, Kobayashi H, Nakagawa T, Arai Y, Kitai R. Simultaneous bilateral hypotensive intracerebral hemorrhages-two case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995. 35: 584-6

8. Kono K, Terada T. Simultaneous bilateral hypertensive putaminal of thalamic hemorrhage: Case report and systematic review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2014. 24: 434-7

9. Laiwattana D, Sangsawang B, Sangsawang N. Primary multiple simultaneous intracerebral hemorrhages between 1950 and 2013: Analysis of data on age, sex and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2014. 4: 102-14

10. Lee SH, Kim BJ, Roh JK. Silent microbleeds are associated with volume of primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006. 66: 430-2

11. Lee SH, Lee ST, Kim BJ, Park HK, Kim CK, Jung KH. Dynamic temporal change of cerebral microbleeds: Long-term follow-up MRI study. PLoS One. 2011. 6: e25930

12. Li X, Zhang L, Wolfe CDA, Wang Y. Incidence and long-term survival of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage overtime: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2022. 13: 819737

13. Lin CN, Howng SL, Kwan AL. Bilateral simultaneous hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages. Gaoxiong Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 1993. 9: 266-75

14. Lin WM, Yang TY, Weng HH, Chen CF, Lee MH, Yang JT. Brain microbleeds: Distribution and influence on hematoma and perihematomal edema in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuroradiol J. 2013. 26: 184-90

15. Mitaki S, Nagai A, Oguro H, Yamaguchi S. Serum lipid fractions and cerebral microbleeds in a healthy Japanese population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017. 43: 186-91

16. Perez J, Scherle C, Machado C. Subsequent bilateral thalamic haemorrhage. BMJ Case Rep. 2009. 2009: bcr042009.1734

17. Sunada I, Nakabayashi H, Matsusaka Y, Nishimura K, Yamamoto S. Simultaneous bilateral thalamic hemorrhage: Case report. Radiat Med. 1999. 17: 359-61

18. Yen CP, Lin CL, Kwan AL, Lieu AS, Hwang SL, Lin CN. Simultaneous multiple hypertensive intracerebral haemorrhages. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005. 147: 393-9

19. Zhao J, Chen Z, Wang Z, Yu Q, Yang W. Simultaneous bilateral basal ganglia hemorrhage. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2016. 50: 275-9