- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arizona, Phoenix, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, United States.

Correspondence Address:

María José Cavagnaro, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arizona, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_456_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: María José Cavagnaro1, José Manuel Orenday-Barraza2, Amna Hussein1, Mauricio J. Avila3, Dara Farhadi1, Angelica Alvarez Reyes3, Isabel L. Bauer1, Naushaba Khan1, Ali A. Baaj1. Surgical management of dropped head syndrome: A systematic review. 17-Jun-2022;13:255

How to cite this URL: María José Cavagnaro1, José Manuel Orenday-Barraza2, Amna Hussein1, Mauricio J. Avila3, Dara Farhadi1, Angelica Alvarez Reyes3, Isabel L. Bauer1, Naushaba Khan1, Ali A. Baaj1. Surgical management of dropped head syndrome: A systematic review. 17-Jun-2022;13:255. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=11658

Abstract

Background: Dropped head syndrome (DHS) is uncommon and involves severe weakness of neck-extensor muscles resulting in a progressive reducible cervical kyphosis. The first-line management consists of medical treatment targeted at diagnosing underlying pathologies. However, the surgical management of DHS has not been well studied.

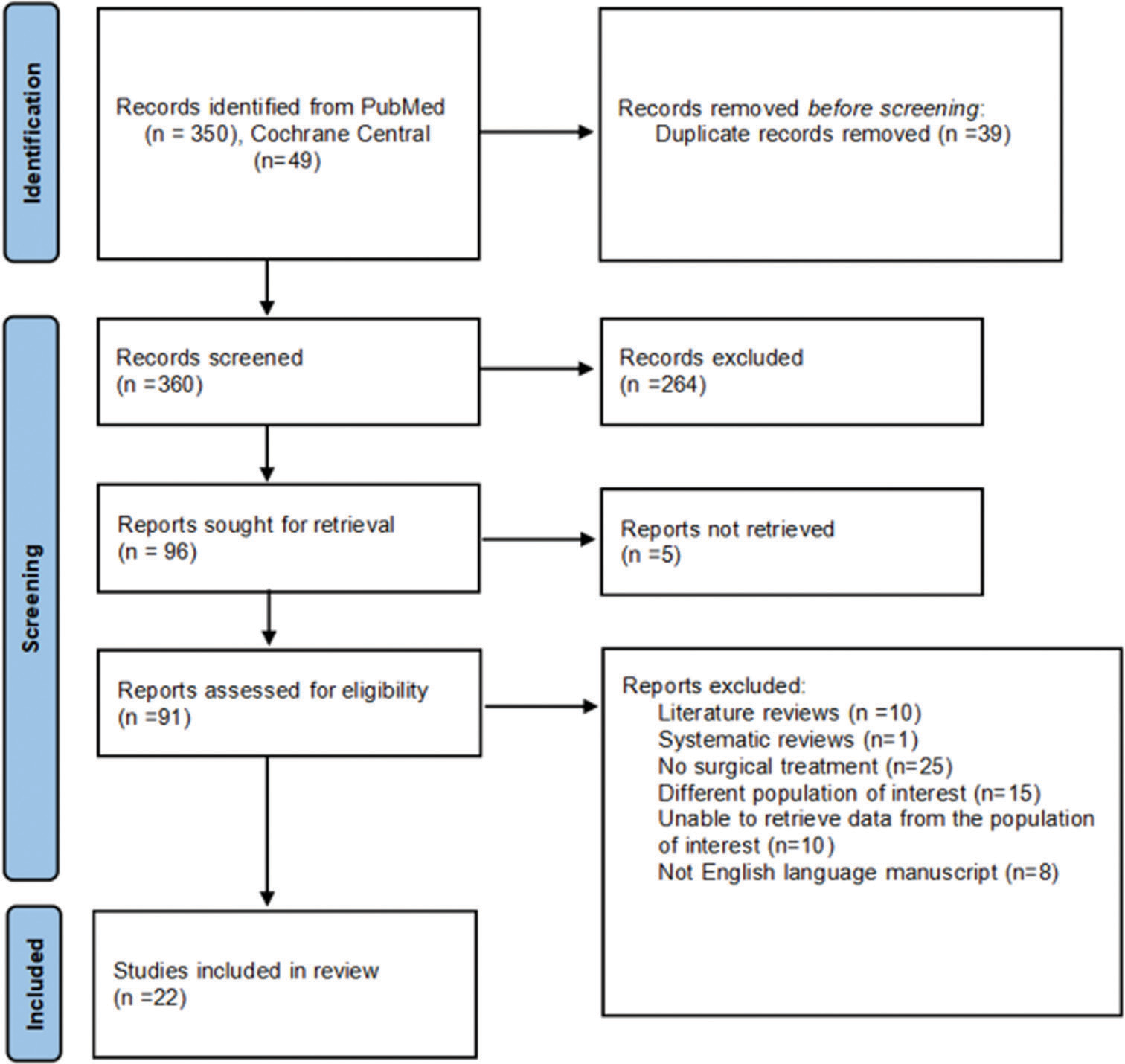

Methods: Here, we systematically reviewed the PubMed and Cochrane databases for DHS using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. All relevant articles up to March 31, 2022, were analyzed. The patient had to be ≥18 years with DHS and had to have undergone surgery with outcomes data available. Outcomes measurements included neurological status, rate of failure (RF), horizontal gaze, and complications.

Results: A total of 22 articles selected for this study identified 54 patients who averaged 68.9 years of age. Cervical arthrodesis without thoracic extension was performed in seven patients with a RF of 71%. Cervicothoracic arthrodesis was performed in 46 patients with an RF of 13%. The most chosen upper level of fusion was C2 in 63% of cases, and the occiput was included only in 13% of patients. All patients neurologically stabilized or improved, while 75% of undergoing anterior procedures exhibited postoperative dysphagia and/or airway-related complications.

Conclusion: The early surgery for patients with DHS who demonstrate neurological compromise or progressive deformity is safe and effective and leads to excellent outcomes.

Keywords: Cervical kyphosis, Cervical spine, Dropped head syndrome, Isolated neck extensor myopathy, Spine surgery

INTRODUCTION

Dropped head syndrome (DHS) is rare and involves severe weakness of the cervical extensor muscles resulting in a progressive reducible severe kyphosis.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

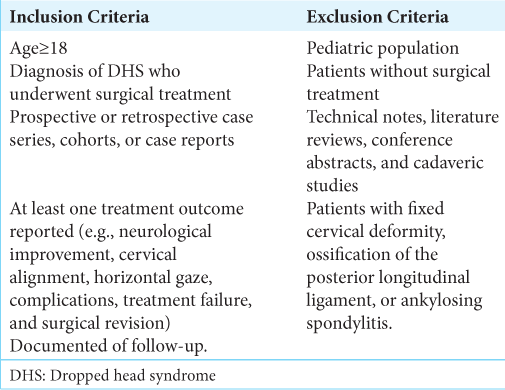

A comprehensive systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.[

Methodological quality assessment

Methodological quality assessment was performed using a tool specifically designed by Murad et al.[

RESULTS

Inclusion of 22 articles

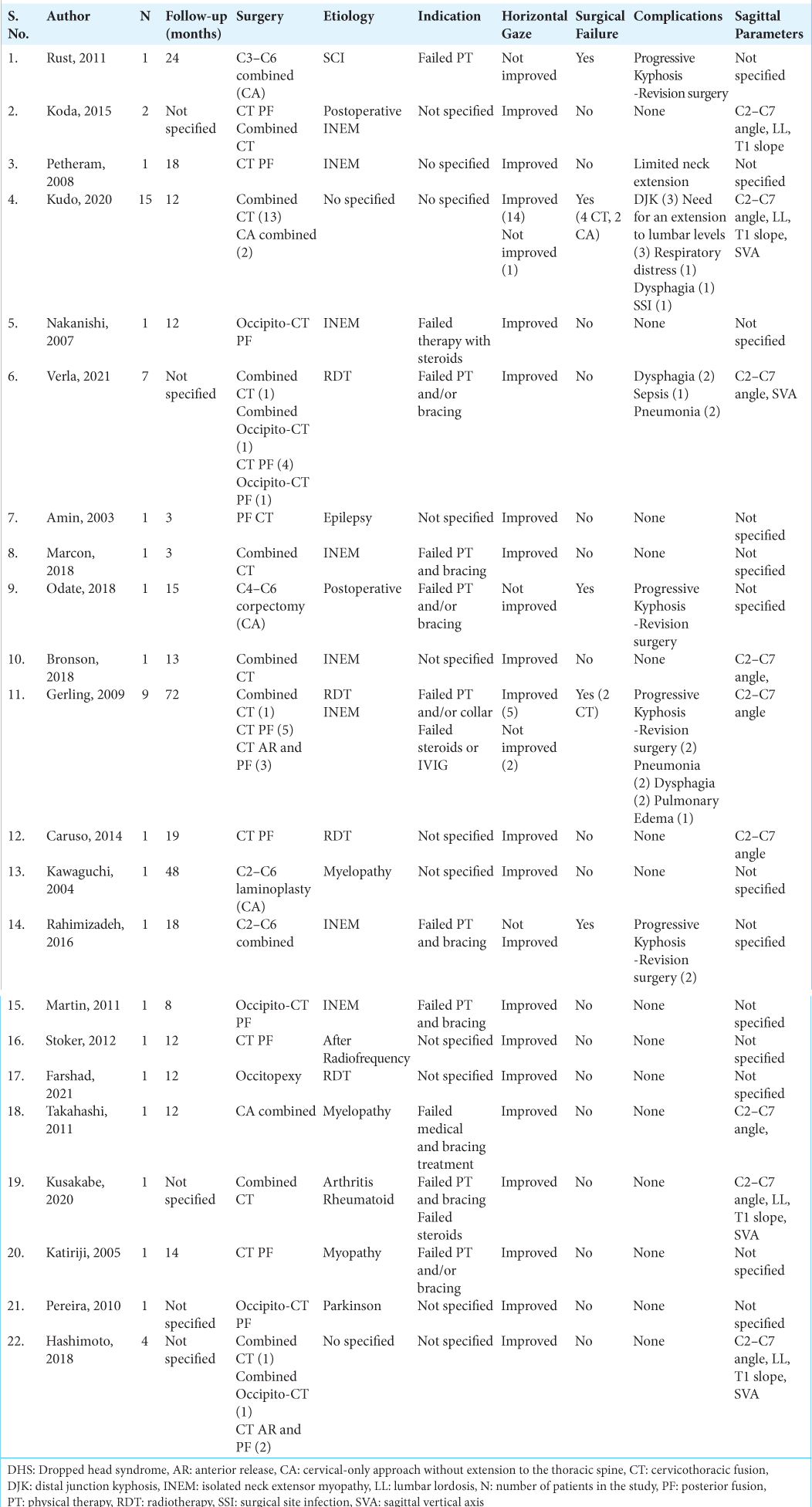

We finally chose 22 articles for analysis [

Symptoms

The most common symptoms were inability to lift the head and impaired horizontal gaze with and without gait disturbance (100% of patients). Neurological deficits were present in 11 patients (20.37%), and nine (16.66%) patients presented with difficulty swallowing. Most of the patients also reported preoperative neck or back pain (57.41%).

The presentation of symptoms was gradual in most patients ranging between 1 month and 20 years of preoperative symptoms. Of the articles that reported prior treatments, conservative nonsurgical treatments failed in 25 patients.

Surgical strategies

Surgical strategies were divided into two major groups: cervical arthrodesis alone without thoracic extension (CA) and cervicothoracic arthrodesis (CT). In each strategy, patients were further treated with either posterior fusion alone (PF), anterior release with PF, or anterior fusion with PF (combined approach). Forty-six patients (85% of the analyzed cohort) underwent CT surgery (22 with combined fusion, five anterior releases with PF, and 19 with PF alone) and seven CA surgeries.

CT findings

The most common upper instrumented cervical level was C2 (63%); the occiput was included only in 13% of the patients. The most common lower instrumented vertebra in the thoracic spine was T3 (26%) followed by T4 (21%). Only three of the 46 patients who had CT fusion had an extension of the construction to the lower thoracic levels. With regard to the patients undergoing CA (cervical arthrodesis alone without thoracic extension), surgery included the combined approach in four patients, C3–C6 PF in 1, C2– C6 laminoplasty, and C4–C6 anterior corpectomy and reconstruction in one patient [

C7 pedicle subtraction osteotomies were performed on five patients and posterior vertebral column resection in one patient.

Postoperative neurological outcomes

Neurological examinations improved or remained intact for all patients independent of the approach chosen. Most patients (91.3%) with CT surgery showed improvement in horizontal gaze. Surgical failure was defined as the need for revision surgery for kyphosis progression, impaired horizontal gaze, distal junctional kyphosis, and/or pseudarthrosis.

Surgical failure

The rate of failure for patients with CA was 71%. Surgical failure was observed in six patients (13%) with CT, four with a combined approach, and two with PF. Both patients with failure after PF were treated with wires.

Postoperative surgical and medical complications

Multiple postoperative surgical and medical complications were observed in these 54 patients with DHS. Surgical site infection was observed in one patient (1.8%), one patient expressed limited neck extension after surgery. Twelve medical complications were observed in 11 patients and included five with dysphagia, four with postoperative pneumonia, two with respiratory distress, and one with sepsis. Most medical complications were dysphagia or airway-related complications. About 75% of dysphagia or airway-related complications were observed in patients with combined approaches for anterior fusion or anterior release.

Radiographic outcomes

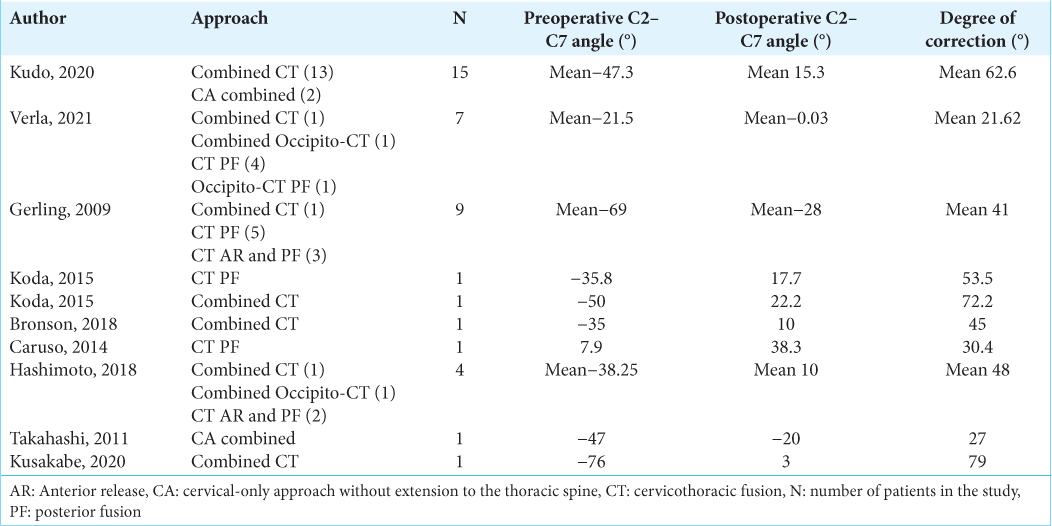

The main sagittal parameter analyzed in this systematic review was the cervical (C2–C7) angle. Pre- and postoperative C2– C7 angle was reported in 41 patients [

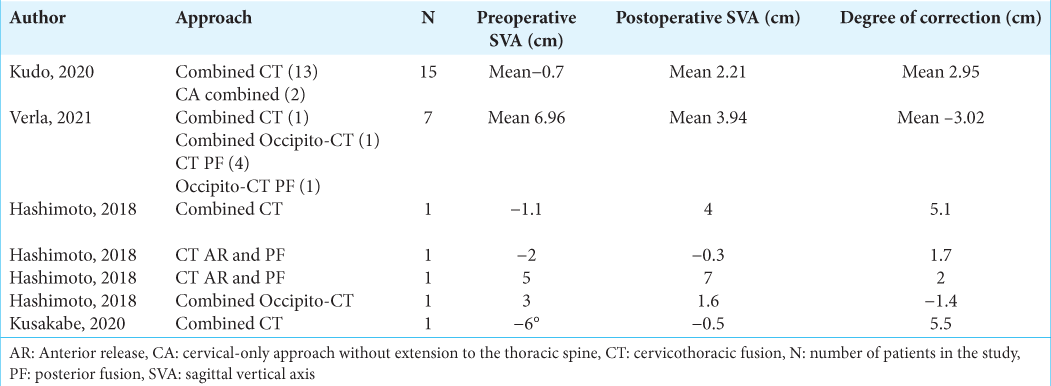

Sagittal vertical axis (SVA) was defined as negative SVA if was < 0 cm and positive SVA if was SVA ≥ 0 cm or P-SVA.[

DISCUSSION

Etiology of DHS

DHS is characterized by either marked neck extensor weakness,[

Treatment of DHS

The treatment of DHS relies on a full etiological work-up, and initial treatment is typically nonsurgical.[

The surgical treatment of DHS aims to restore the horizontal gaze, correct sagittal alignment, and decompress neural elements. In this study, we found a 71% failure rate for patients fused only within the cervical spine (CA patients) to treat DHS.

Successful clinical and radiological outcomes of DHS with CA were only found in two patients (29%) in this systematic review. Of those, Kawaguchi et al. described one patient with cervical stenosis and myelopathy with DHS who greatly improved after cervical laminoplasty. The other patients described by Takahashi et al. underwent C4–C6 corpectomy and C3–C7 posterior fusion.

N-SVA in DHS has been described as a spinopelvic compensation to the cervical deformity and is associated with a better response to surgery.[

Extension of fusion to upper thoracic spine

The extension of the fusion to the upper thoracic segments between T1 and T5 may provide a more stable biomechanical support to the cervical construct and reduces the risk of failure.[

DHS usually shows an enlarged C2–C7 angle, but usually maintained the C0–C2 angle. In this systematic review, C2 was the most chosen upper instrumented level, and the occiput was included only in 13% of the constructions. In addition, an extension of the fusion to the occiput significantly restricts head movements and can lead to significant rates of complications. A recent study showed a 44.5% rate of complications for DHS patients undergoing occipital-cervical fusion.

In this systematic review, combined approaches for deformity correction were slightly preferred over PF. This is likely as combined approaches allow for better restoration of the lordosis. However, medical complications such as dysphagia and those related to the airway were observed most frequently in patients with anterior approaches for fusion or release. Thus, the use of a combined approach for DHS must be carefully weighed against potential early complications after surgery.

In general, rigid cervical deformities are associated with a greater number and grade of osteotomies than flexible deformities; however, surgical osteotomies may be necessary to correct later stages of the disease or severe cases of DHS.[

The amount of deformity correction wanted must be weighted with the risk of complications and expected functional outcomes when deciding between combined approaches, PF, and/or different grades of osteotomies.

Finally, surgical treatment is not the first treatment strategy for DHS, but the likelihood of needing surgery seems to increase when the cause is unknown thus highlighting the importance of a longitudinal follow-up for these patients.

CONCLUSION

The early surgery for patients with DHS who demonstrate neurological compromise or progressive deformity is safe, effective, and leads to excellent outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients’ consent not required as patients’ identities were not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Amin A, Casey AT, Etherington G. Is there a role for surgery in the management of dropped head syndrome?. Br J Neurosurg. 2004. 18: 289-93

2. Brodell JD, Sulovari A, Bernstein DN, Mongiovi PC, Ciafaloni E, Rubery PT. Dropped head syndrome: An update on etiology and surgical management. JBJS Rev. 2020. 8: e0068

3. Drain JP, Virk SS, Jain N, Yu E. Dropped head syndrome: A systematic review. Clin Spine Surg. 2019. 32: 423-9

4. Gerling MC, Bohlman HH. Dropped head deformity due to cervical myopathy: Surgical treatment outcomes and complications spanning twenty years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008. 33: E739-45

5. Hashimoto K, Miyamoto H, Ikeda T, Akagi M. Radiologic features of dropped head syndrome in the overall sagittal alignment of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2018. 27: 467-74

6. Kudo Y, Toyone T, Endo K, Matsuoka Y, Okano I, Ishikawa K. Impact of Spinopelvic sagittal alignment on the surgical outcomes of dropped head syndrome: A multi-center study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020. 21: 382

7. Martin AR, Reddy R, Fehlings MG. Dropped head syndrome: diagnosis and management. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2011. 2: 41-7

8. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018. 23: 60-3

9. Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and examples for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. 372: n160

10. Sharan AD, Kaye D, Malveaux WM, Riew KD. Dropped head syndrome: Etiology and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012. 20: 766-74