- Department of Neurosurgery, Military Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria

Correspondence Address:

Donika Ivova Vezirska, Department of Neurosurgery, Military Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_816_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Vladimir Stoyanov Prandzhev, Nikolay Dinev Georgiev, Donika Ivova Vezirska. Tailored sacroplasty for sacral fracture secondary to an epileptic seizure. 08-Nov-2024;15:409

How to cite this URL: Vladimir Stoyanov Prandzhev, Nikolay Dinev Georgiev, Donika Ivova Vezirska. Tailored sacroplasty for sacral fracture secondary to an epileptic seizure. 08-Nov-2024;15:409. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/13205/

Abstract

Background: Sacral fractures causing neurological deficits secondary to epileptic seizures are very rare. They are traditionally treated by laminectomy and sacral fixation. However, minimally invasive techniques such as sacroplasty offer more limited surgery with decreased morbidity. Here, a 23-year-old male with a seizure-induced sacral fracture was successfully treated with a decompressive laminectomy and transcorporal sacroplasty.

Methods: After a grand-mal seizure, a 23-year-old male presented with severe paraparesis accompanied by bilateral S1/S2 radiculopathy and urinary/fecal incontinence (Gibbons grade 4). When studies documented a Roy-Camille type 2 sacral fracture with severe central compression of the S1/S2 spinal canal, he underwent an S1-S2 laminectomy with transcorporal sacroplasty.

Results: On the 1st postoperative day, he ambulated without assistance and demonstrated only mild residual sensory deficits (Gibbons grade 2); 1-month later, he walked without assistance.

Conclusion: A 23-year-old male with a seizure-induced sacral fracture was successfully treated with a decompressive S1/S2 laminectomy/transcorporal sacroplasty.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Sacral fracture, Sacroplasty, Seizure-induced fractures

INTRODUCTION

Seizure-induced spinal fractures typically involve the midthoracic to thoracolumbar regions.[

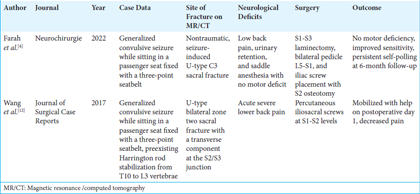

We were only able to identify two cases of purely sacral fractures that occurred following epileptic seizures.[

METHODS

Presentation and surgery

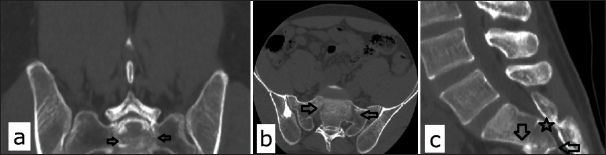

A 23-year-old male presented with cauda equina syndrome (Gibbons grade 4) secondary to an unprovoked epileptic seizure. On examination, he exhibited lower-limb paraparesis 2/5 on the Medical Research Scale with loss of bladder and bowel control. The lumbar computed tomography scan showed a U-shaped sacral fracture with bilateral lateral mass damage and posterior dislocation of the S1-S2 segment engaging the promontorium [

Figure 1:

Appearance of the sacral fracture on a computed tomography scan: (a) Coronal plane. Black arrows point to the vertical parts of the fracture on each side. (b) Axial plane. Black arrows point to the oblique parts of the fracture on each side. (c) Sagittal plane. Black arrows point to the anterior and posterior end of the transverse part of the fracture. A black star indicates the level of the most significant central canal stenosis.

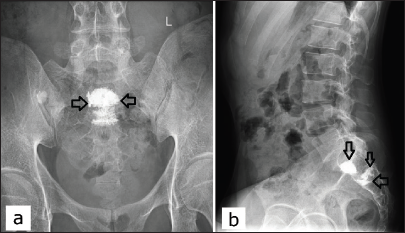

Figure 2:

Appearance of the sacral fracture on a Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan: (a) Sagittal plane. Black arrows point to the transverse part of the fracture. A black star indicates the level of the most significant central canal stenosis. (b) Coronal plane. Black arrows point to the vertical parts of the fracture. (c) Axial plane. The black star indicates the level of the most significant central canal stenosis.

RESULTS

Postoperative course

On postoperative day 1, the patient was mobilized without a walking aid; the Visual Analog Scale score deteriorated from 9.0 to 3.0; the patient was discharged on postoperative day 4 with only mild tenderness in the operative area and a mild residual bilateral sensory deficit in S1-S2 dermatome distribution (Gibbons grade 2). Antiepileptic therapy was also optimized, and the patient was switched to levetiracetam from valproic acid.

One month later, he ambulated without assistance, exhibiting no residual limb, and sensory and sphincteric complaints had fully resolved. Follow-up X-ray studies showed satisfactory distribution of bone cement in the transverse S1/S2 fracture site with stable consolidation of the sacrum [

Figure 3:

Postoperative X-ray image after 1 month. (a) Anterior-posterior view. (b) Lateral view. The bone cement is distributed along the transverse fracture line, mostly in the superior endplate of S2 and the anterior part of S1 which had a discrete fracture line on the preoperative computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The arrows point to the bone cement distribution along the fracture line which is shown to be mostly in the transverse and oblique plane (the bottom part of the U-shape that is prone to the largest axial load).

DISCUSSION

Incidence of vertebral fractures in patients with epilepsy

Vertebral fractures secondary to tonic-clonic seizures are most commonly attributed to (1) the powerful contraction of the paraspinal muscles during a seizure (primary) and (2) falls or other accidents resulting from the seizure.[

Antiepileptic therapy may include liver enzyme-inducing drugs, such as valproic acid, that are discussed to promote osteoporosis, but there has not been a unanimous conclusion on whether they could be a reason for the increased risk of bone fractures in epileptic patients.[

Sacral fracture diagnosis and management

Sacral fractures are often misdiagnosed and/or missed on imaging studies and undergo a variety of decompressions/fusions.[

Tailored sacroplasty for sacral fracture management

The major issue was to decompress the cauda equina compression attributed to the S1-S2 sacral fracture (Roy-Camille type 2). Here, we assumed that the vertical incomplete unilateral fracture of the anterior portion of the lateral mass was stable; the bone cement was utilized to stabilize the transverse/oblique parts of the fracture to prevent malunion. An approximate illustration of our technique is shown on the diagram [

According to Frey et al., the major axial load is carried by the sacral corpus; bone cement augmentation used here at the fracture zone would prevent micromotion, stabilize the segment, and significantly decrease pain.[

Implantation of fixation device

Implantation of fixation devices overall increases infection rates, the risks of hardware malfunction, and the potential for catastrophic consequences from future epileptic seizures.[

CONCLUSION

A 23-year-old male with a seizure-induced sacral fracture was successfully treated with a decompressive S1/S2 laminectomy/transcorporal sacroplasty.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Aprato A, Branca Vergano L, Casiraghi A, Liuzza F, Mezzadri U, Balagna A. Consensus for management of sacral fractures: From the diagnosis to the treatment, with a focus on the role of decompression in sacral fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2023. 24: 46

2. Barber LA, Katsuura Y, Qureshi S. Sacral fractures: A review. HSS J. 2023. 19: 234-46

3. Beucler N, Tannyeres P, Dagain A. Surgical management of unstable U-shaped sacral fractures and tile C pelvic ring disruptions: Institutional experience in light of a narrative literature review. Asian Spine J. 2023. 17: 1155-67

4. Farah K, Meyer M, Prost S, Dufour H, Fuentes S. An unusual traumatic sacral-U shape fracture occurring during a grand mal epileptic seizure. Neurochirurgie. 2022. 68: 255-7

5. Frey ME, DePalma MJ, Cifu DX, Bhagia SM, Carne W, Daitch JS. Percutaneous sacroplasty for osteoporotic sacral insufficiency fractures: A prospective, multicenter, observational pilot study. Spine J. 2008. 8: 367-73

6. Li P, Qiu D, Shi H, Song W, Wang C, Qiu Z. Isolated decompression for transverse sacral fractures with cauda equina syndrome. Med Sci Monit. 2019. 25: 3583-90

7. Mahmood B, Pasternack J, Razi A, Saleh A. Safety and efficacy of percutaneous sacroplasty for treatment of sacral insufficiency fractures: A systematic review. J Spine Surg. 2019. 5: 365-71

8. Patsalos PN. Pharmacokinetic profile of levetiracetam: Toward ideal characteristics. Pharmacol Ther. 2000. 85: 77-85

9. Robles LA, Guerrero-Maldonado A. Seizure-induced spinal fractures: A systematic review. Int J Spine Surg. 2022. 16: 521-9

10. Souverein PC, Webb DJ, Weil JG, Van Staa TP, Egberts AC. Use of antiepileptic drugs and risk of fractures: Case-control study among patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2006. 66: 1318-24

11. Vestergaard P. Epilepsy, osteoporosis and fracture risk-a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005. 112: 277-86

12. Wang Q, Verrall I, Walker R, Tetsworth K, Drobetz H. U-type bilateral sacral fracture with spino-pelvic dissociation caused by epileptic seizure. J Surg Case Rep. 2017. 2017: rjx043