- Department of Surgical Specialties and Neurosurgery, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Correspondence Address:

Magno Rocha Freitas Rosa, Department of Surgical Specialties and Neurosurgery, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_635_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Magno Rocha Freitas Rosa, Thainá Zanon Cruz, Eduardo Vasconcelos Magalhães Junior, Flavio Nigri. Tetraventricular noncommunicating hydrocephalus: Case report and literature review. 19-Oct-2021;12:519

How to cite this URL: Magno Rocha Freitas Rosa, Thainá Zanon Cruz, Eduardo Vasconcelos Magalhães Junior, Flavio Nigri. Tetraventricular noncommunicating hydrocephalus: Case report and literature review. 19-Oct-2021;12:519. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=11193

Abstract

Background: Tetraventricular hydrocephalus is a common presentation of communicating hydrocephalus. Conversely, cases with noncommunicating etiology impose a diagnostic challenge and are often neglected and underdiagnosed. Herein, we present a review of literature for clinical, diagnostic, and surgical aspects regarding noncommunicating tetrahydrocephalus caused by primary fourth ventricle outlet obstruction (FVOO), illustrating with a case from our service.

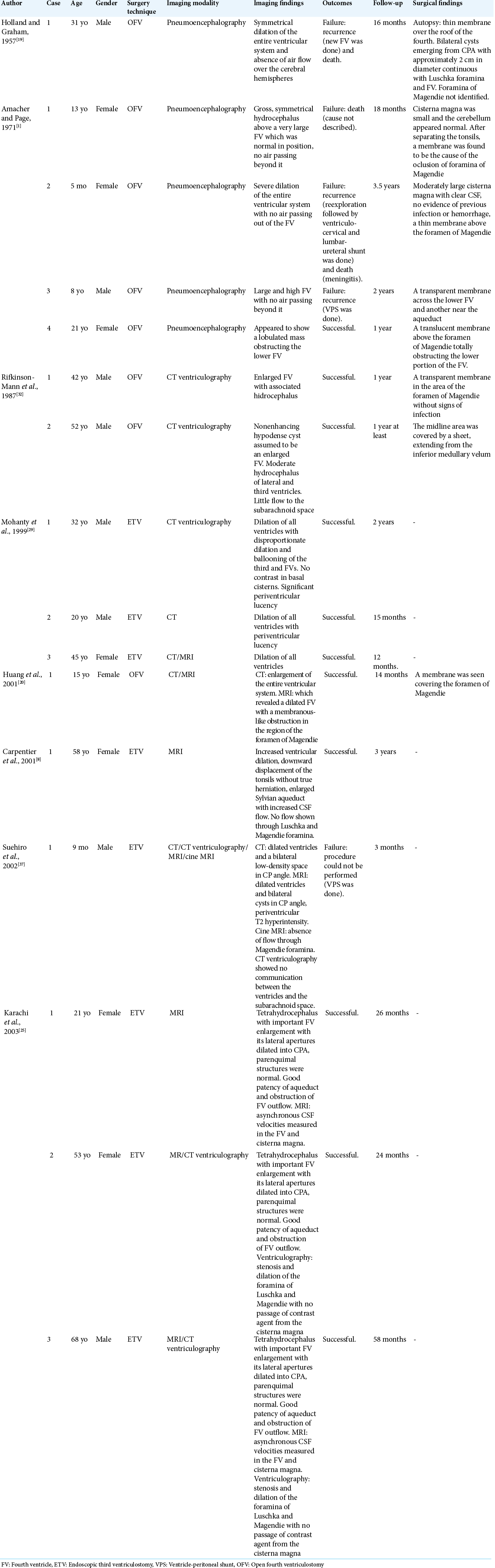

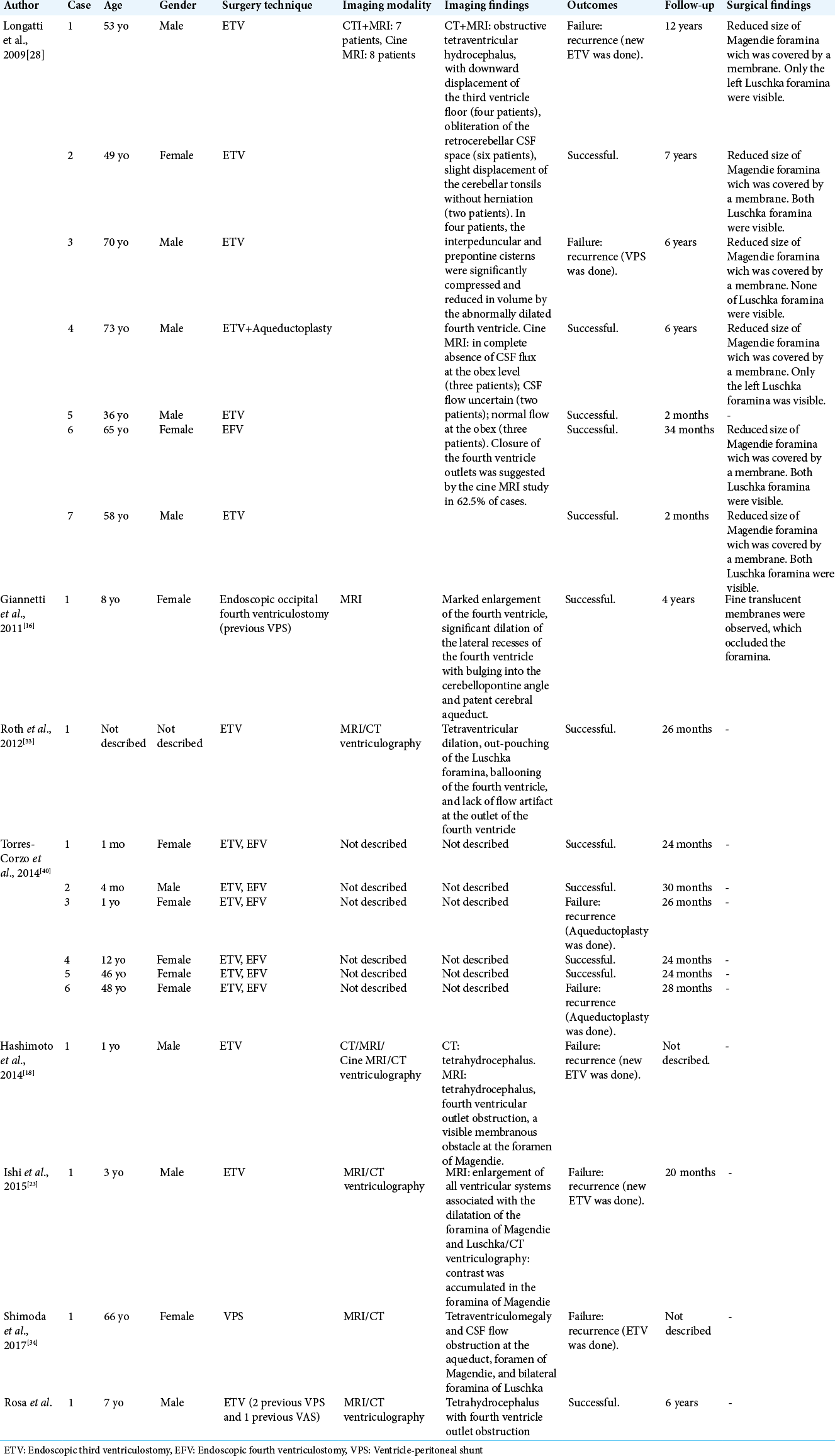

Methods: We performed a research on PubMed database crossing the terms “FVOO,” “tetraventriculomegaly,” and “hydrocephalus” in English. Fifteen articles (a total of 34 cases of primary FVOO) matched our criteria and were, therefore, included in this study besides our own case.

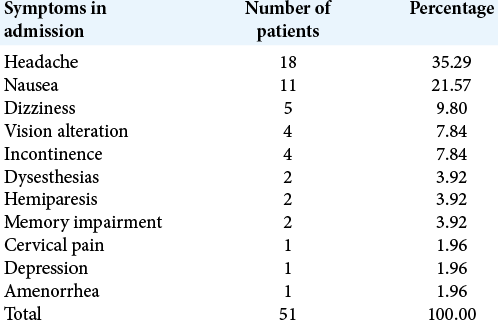

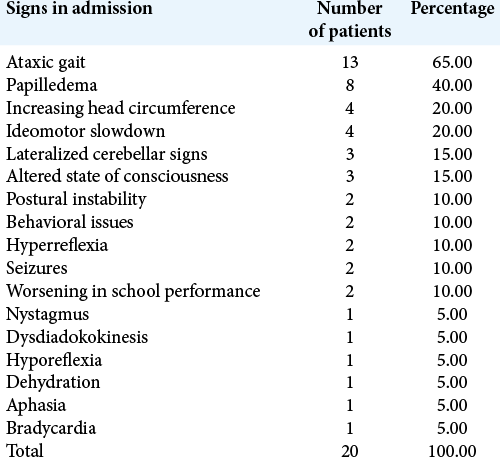

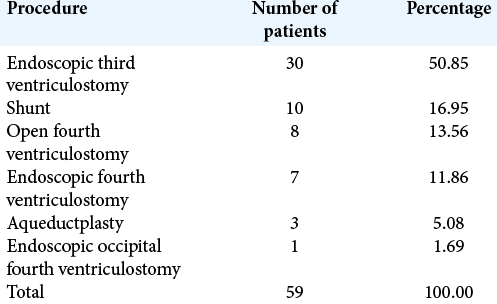

Results: Most cases presented in adulthood (47%), equally divided between male and female. Clinical presentation was unspecific, commonly including headache, nausea, and dizziness as symptoms (35.29%, 21.57%, and 9.80%, respectively), with ataxic gait (65%) and papilledema (40%) being the most frequent signs. MRI and CT were the imaging modalities of choice (11 patients each), often associated with CSF flow studies, such as cine MRI and CT ventriculogram. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) was both the most popular and effective surgical approach (50.85% of cases, with 18.91% of recurrence) followed by ventricle-peritoneal shunt (16.95% of patients, 23.0% of recurrence).

Conclusion: FVOO stands for a poorly understood etiology of noncommunicating tetrahydrocephalus. With the use of ETV, these cases, once hopeless, had its morbimortality and recurrence reduced greatly. Therefore, its suspicion and differentiation from other forms of tetrahydrocephalus can improve its natural course, reinforcing the importance of its acknowledgment.

Keywords: Fourth ventricle outlet obstruction, Hydrocephalus, Tetraventriculomegaly

INTRODUCTION

Tetraventricular hydrocephalus is a common presentation of communicating hydrocephalus. Detecting, among tetraventricular hydrocephalus, cases with noncommunicating etiology may open the possibility of different surgical treatment strategies other than performing ventricular shunting. Herein, we report a challenging case of tetraventricular noncommunicating hydrocephalus caused by primary fourth ventricle outlets obstruction (FVOO) that had undergone multiple shunt revisions. Furthermore, we offer a review of literature searching for clinical and imaging clues for early diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

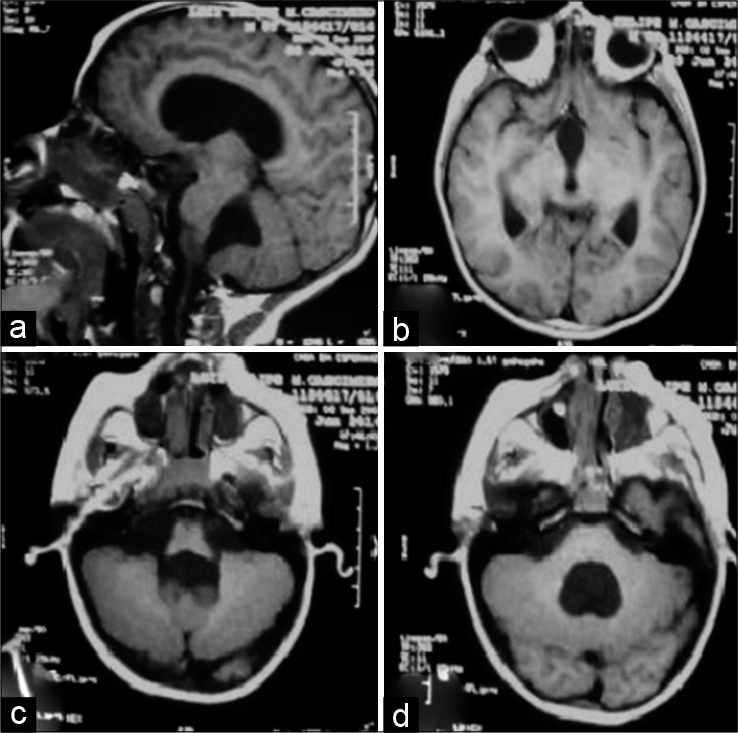

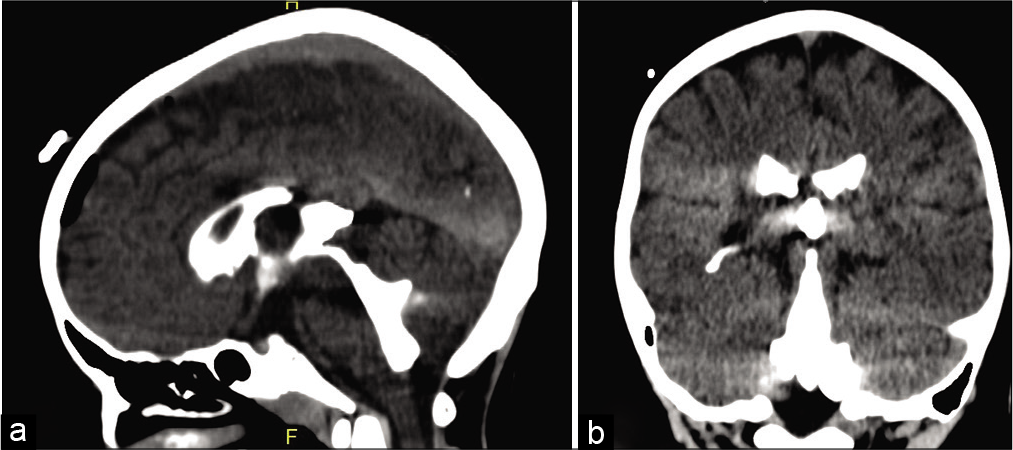

A 7 year-old male patient with tetraventricular hydrocephalus presenting learning difficulties had been submitted to an implantation of a programmable ventricle-peritoneal shunt (VPS), Sophysa®, in October 2014. In January 2015, he was readmitted to the hospital presenting abdominal pain, vomits, and VI and VII cranial nerve palsy. MRI showed tetraventricular enlargement. The VPS was revised but no signs of infection or obstruction were detected. The VPS was then replaced for a medium pressure valve. Two weeks later, under a new onset of intracranial hypertension (ICH), the VPS was removed and an external ventricular drainage (EVD) was implanted. The patient persisted somnolent, with apathy and intense nausea during the 1st days postsurgery and after stabilization of the neurological status, a low-pressure ventriculoatrial shunt (VAS) was installed in March 2015. Three months later, a VAS revision was necessary due to obstruction of the proximal catheter that was attached to the choroid plexus. An EVD was implanted. After VAS revision, the EVD was closed for 3 days, then removed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital. On the next day, the patient returned to the hospital with symptoms and signs of ICH. The former neurosurgeon contacted our neurosurgical team, and the patient was transferred to our neurosurgical service. He was admitted in July 2015 presenting a decreased level of consciousness (GCS = 12), vomiting, and bradycardia. After a new EVD procedure, intracranial pressure was monitored for 3 days and recorded within normal values. The neurological status improved and the EVD was withdrawn. Two days later, he presented an episode of apparent tonic–clonic seizure, accompanied by bradycardia, arterial hypotension, vomiting, and became aphasic. The previous implanted VAS was withdrawn and an EVD was reimplanted. As we noticed that the MRI showed third ventricular dilation with downward bulging of its floor [

DISCUSSION

There are only a few cases reported, each one presenting different and variable signs and symptoms, and equally variable treatment strategies to obtain successful outcomes.[

FVOO is an uncommon situation usually associated with posterior fossa congenital malformations (i.e. Dandy–Walker syndrome and Chiari malformation); tuberous sclerosis; infection (i.e. meningoencephalitis and arachnoiditis); trauma; postsurgical adhesions; or tumors.[

Background

Dandy was probably the first to describe in paper, in early 1920s, FVOO as a cause of tetrahydrocephalus. In a time, while a great proportion of the scientific community was still debating whether fourth ventricle apertures (Luschka’s and Magendie’s foramina) were naturally present or simply artefact of dissection and whether the ventricle system had a communication or worked isolated from the subarachnoid space,[

Dandy was also perceptive in observing that even though FVOO was an uncommon cause of noncommunicating hydrocephalus and usually secondary, there was also another group of patients that shared a primary, or idiopathic, etiology, when it could not be linked to another associated pathology.

Later, in 1958, Holland and Graham[

After many years, Amacher and Page,[

Physiopathology

The most solid theory in vogue in the matter so far postulates that the development of semipermeable membranes obstructing the foramina could be responsible for the condition. Theoretically, the intermittent CSF flow would allow good clinical tolerance for some time, maybe even decades, until some event, such as hemorrhage, meningitis, and arachnoiditis, would lead to a decompensated permeability, and, following it, CSF accumulation upstream.[

CASE REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Inclusion criteria

We performed a research on PubMed database crossing the terms “FVOO,” “tetraventriculomegaly,” and “hydrocephalus” in English. Inclusion criteria included cases of tetrahydrocephalus without a concomitant malformation or other secondary cause that could correspond to a confounding factor to primary or idiopathic FVOO. Excluding criteria were secondary or etiologic nonspecified cases, communicating hydrocephalus or case reports that did not provide enough information to allow differentiation of the clinical course, radiological findings, treatment of choice, and outcomes between primary and secondary etiologies. Fifteen articles (a total of 34 cases of primary FVOO) matched our criteria and were, therefore, included in this study besides our own case.

Epidemiological and clinical findings

In our series of 35 cases [

When it comes to this entity, clinical signs and symptoms are variable and little can offer to diagnostic confirmation. The most common symptoms observed were headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, vision disturbance, and incontinence [

Imaging diagnosis

It is easy to identify dilation or augmented CSF collection in the fourth ventricle as a characteristic radiological finding in cases of FVOO.[

In our series, 47 different radiological examinations were used in the 35 patients, with MRI and CT being the most commonly observed (11 patients each), followed by CT ventriculography and cine MRI (10 patients each), and pneumoencephalography, due its historical role in diagnosing such patients (five cases). Perhaps, because of its widely availability and fast technique, CT is still frequently used as a first radiological examination in these cases, even though it does not seal the FVOO as the etiology for hydrocephalus, once the patients usually arrive without any previous examination or diagnosis and in poor general condition. When available, MRI and cine MRI are commonly used as the next step in radiological investigation, even though CT ventriculography consists of an important option and is also frequently performed, especially in patients with an EVD implanted, such as the case we treated in our institution.

Surgical techniques

The first surgical approaches of primary FVOO were focused on the logical idea that if obstruction of the foramina was the cause of the condition, then restoring the physiological pathway would be the natural choice.[

Contemporarily, shunting techniques took place and became a preferable method in hydrocephalus cases, especially the communicating forms. The first types of shunts, very popular in the past, such as the ventriculoureteral shunting in the 1950s,[

The use of shunts, however, is also associated with numerous complications, once it involves the maintenance of a functioning catheter connecting the subarachnoid space and the peritoneum or atrium. The obstruction and malfunction of the catheter can lead to recurrence of the hydrocephalus and the need to reassess the procedure; overdrainage can lead to headache and intracranial bleeding;[

Some decades after, in the 1990s, Chai[

It was Mohanty et al. in 1999[

As a final consideration, it is important to bring up the newest approach in vogue: the transaqueductal endoscopic fourth ventriculostomy (EFV).[

CONCLUSION

FVOO stands for a neglected etiology of noncommunicating tetrahydrocephalus although the first reports of this entity can be traced to the early 20th century.

The clinical features are not specific and do not allow its differentiation from other forms of hydrocephalus. However, with modern techniques of diagnosis, specially MRI, we can rely on noninvasive and highly elucidative examinations for its recognition, once there’s a suspicion.

Several surgical techniques were once used to treat the condition. Initially, open exploration of posterior fossa was performed, with poor, unsatisfactory results. VPS was also very frustrating as an approach of choice in these patients. Only after the addition of endoscopic techniques to the surgical repertoire, these cases, once apparently hopeless, presented a reproducible improvement in morbidity and mortality, with ETV being considered the surgery of choice, followed, when not feasible, by EFV.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Amacher AL, Page LK. Hydrocephalus due to membranous obstruction of the fourth ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1971. 35: 672-6

2. Bal RK, Singh P, Harjai MM. Intestinal volvulus-a rare complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999. 15: 577-8

3. Bales J, Morton RP, Airhart N, Flum D, Avellino AM. Transanal presentation of a distal ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter: Management of bowel perforation without laparotomy. Surg Neurol Int. 2016. 7: S1150-3

4. Bonfield CM, Weiner GM, Bradley MS, Engh JA. Vaginal extrusion of a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt catheter in an adult. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015. 6: 97-9

5. Browd SR, Gottfried ON, Ragel BT, Kestle JR. Failure of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: Part II: Overdrainage, loculation, and abdominal complications. Pediatr Neurol. 2006. 34: 171-6

6. Browd SR, Ragel BT, Gottfried ON, Kestle JR. Failure of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: Part I: Obstruction and mechanical failure. Pediatr Neurol. 2006. 34: 83-92

7. Calabro F, Arcuri T, Jinkins JR. Blake’s pouch cyst: An entity within the Dandy-Walker continuum. Neuroradiology. 2000. 42: 290-5

8. Carpentier A, Brunelle F, Philippon J, Clemenceau S. Obstruction of Magendie’s and Luschka’s foramina. CineMRI aetiology and pathogenesis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001. 143: 517-21

9. Chai WX. Long-term results of fourth ventriculocisternostomy in complex versus simplex atresias of the fourth ventricle outlets. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995. 134: 27-34

10. Coleman CC, Troland CE. Congenital atresia of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie with report of two cases of surgical cure. J Neurosurg. 1948. 5: 84-8

11. Cornips EM, Overvliet GM, Weber JW, Postma AA, Hoeberigs CM, Baldewijns MM. The clinical spectrum of Blake’s pouch cyst: Report of six illustrative cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010. 26: 1057-64

12. Dandy WE. The diagnosis and treatment of hydrocephalus due to occlusions of the foramina of Magendie and Luschka. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1921. 32: 112-24

13. Ferrer E, de Notaris M. Third ventriculostomy and fourth ventricle outlets obstruction. World Neurosurg. 2013. 79: S20.e9-13

14. Fewel ME, Garton HJ. Migration of distal ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter into the heart. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2004. 100: 206-11

15. Filka J, Huttova M, Tuharsky J, Sagat T, Kralinsky K, Krcmery V. Nosocomial meningitis in children after ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion. Acta Paediatr. 1999. 88: 576-8

16. Giannetti AV, Malheiros JA, da Silva MC. Fourth ventriculostomy: An alternative treatment for hydrocephalus due to atresia of the Magendie and Luschka foramina. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011. 7: 152-6

17. Hai A, Rab AZ, Ghani I, Huda MF, Quadir AQ. Perforation into gut by ventriculoperitoneal shunts: A report of two cases and review of the literature. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011. 16: 31-3

18. Hashimoto H, Maeda A, Kumano K, Kimoto T, Fujisawa Y, Akai T. Rapid deterioration of primary fourth ventricular outlet obstruction resulting in syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Pediatr Int. 2014. 56: e30-2

19. Holland HC, Graham WL. Congenital atresia of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie with hydrocephalus; report of a case in an adult. J Neurosurg. 1958. 15: 688-94

20. Huang YC, Chang CN, Chuang HL, Scott RM. Membranous obstruction of the fourth ventricle outlet. A case report. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001. 35: 43-7

21. Hung AL, Vivas-Buitrago T, Adam A, Lu J, Robison J, Elder BD. Ventriculoatrial versus ventriculoperitoneal shunt complications in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017. 157: 1-6

22. Irby PB, Wolf JS, Schaeffer CS, Stoller ML. Long-term follow-up of ventriculoureteral shunts for treatment of hydrocephalus. Urology. 1993. 42: 193-7

23. Ishi Y, Asaoka K, Kobayashi H, Motegi H, Sugiyama T, Yokoyama Y. Idiopathic fourth ventricle outlet obstruction successfully treated by endoscopic third ventriculostomy: A case report. Springerplus. 2015. 4: 565

24. Joseph VB, Raghuram L, Korah IP, Chacko AG. MR ventriculography for the study of CSF flow. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24: 373-81

25. Karachi C, Le Guerinel C, Brugieres P, Melon E, Decq P. Hydrocephalus due to idiopathic stenosis of the foramina of Magendie and Luschka. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 2003. 98: 897-902

26. Kasapas K, Varthalitis D, Georgakoulias N, Orphanidis G. Hydrocephalus due to membranous obstruction of Magendie’s foramen. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015. 57: 68-71

27. Kulkarni AV, Drake JM, Mallucci CL, Sgouros S, Roth J, Constantini S. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the treatment of childhood hydrocephalus. J Pediatr. 2009. 155: 254-9.e1

28. Longatti P, Fiorindi A, Martinuzzi A, Feletti A. Primary obstruction of the fourth ventricle outlets: Neuroendoscopic approach and anatomic description. Neurosurgery. 2009. 65: 1078-85

29. Mohanty A, Biswas A, Satish S, Vollmer DG. Efficacy of endoscopic third ventriculostomy in fourth ventricular outlet obstruction. Neurosurgery. 2008. 63: 905-14

30. Neiter E, Guarneri C, Pretat PH, Joud A, Marchal JC, Klein O. Semiology of ventriculoperitoneal shunting dysfunction in children-a review. Neurochirurgie. 2016. 62: 53-9

31. Oertel JM, Mondorf Y, Schroeder HW, Gaab MR. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of far distal obstructive hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2010. 152: 229-40

32. Rifkinson-Mann S, Sachdev VP, Huang YP. Congenital fourth ventricular midline outlet obstruction. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1987. 67: 595-9

33. Roth J, Ben-Sira L, Udayakumaran S, Constantini S. Contrast ventriculo-cisternography: An auxiliary test for suspected fourth ventricular outlet obstruction. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012. 28: 453-59

34. Shimoda Y, Murakami K, Narita N, Tominaga T. Fourth ventricle outlet obstruction with expanding space on the surface of cerebellum. World Neurosurg. 2017. 100: 711.e1-5

35. Sigaroudinia MO, Baillie C, Ahmed S, Mallucci C. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis-a rare complication of ventriculoperitonealentriculoper. J Pediatr Surg. 2008. 43: E31-3

36. Spennato P, Ruggiero C, Aliberti F, Nastro A, Mirone G, Cinalli G. Third ventriculostomy in shunt malfunction. World Neurosurg. 2013. 79: S22.e21-6

37. Suehiro T, Inamura T, Natori Y, Sasaki M, Fukui M. Successful neuroendoscopic third ventriculostomy for hydrocephalus and syringomyelia associated with fourth ventricle outlet obstruction. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000. 93: 326-9

38. Takami H, Shin M, Kuroiwa M, Isoo A, Takahashi K, Saito N. Hydrocephalus associated with cystic dilation of the foramina of Magendie and Luschka. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010. 5: 415-8

39. Torkildsen A. A follow-up study of 14 to 20 years after ventriculo-cisternostomy. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1960. 35: 114-2

40. Torres-Corzo J, Sanchez-Rodriguez J, Cervantes D, Vecchia RR, Muruato-Araiza F, Hwang SW. Endoscopic transventricular transaqueductal Magendie and Luschka foraminoplasty for hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2014. 74: 426-35

41. Zhao R, Shi W, Yu J, Gao X, Li H. Complete intestinal obstruction and necrosis as a complication of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt in children: A report of 2 cases and systematic literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015. 94: e1375