- School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Correspondence Address:

Nicole M. Castillo-Huerta School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, San Martín de Porres, Lima, Peru.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_940_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Jhon E. Bocanegra-Becerra, Nicole M. Castillo-Huerta, Alonso Ludeña-Esquivel, O. Nicole Torres-García, Martha I. Vilca-Salas, Milagros F. Bermudez-Pelaez. The humanitarian aid of neurosurgical missions in Peru: A chronicle and future perspectives. 25-Nov-2022;13:545

How to cite this URL: Jhon E. Bocanegra-Becerra, Nicole M. Castillo-Huerta, Alonso Ludeña-Esquivel, O. Nicole Torres-García, Martha I. Vilca-Salas, Milagros F. Bermudez-Pelaez. The humanitarian aid of neurosurgical missions in Peru: A chronicle and future perspectives. 25-Nov-2022;13:545. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12029

Abstract

Background: The unmet neurosurgical need has remained patent in developing countries, including Peru. However, continuous efforts to overcome the lack of affordable care have been achieved, being neurosurgical missions one of the main strategies. We chronicle the humanitarian labor of organizations from high-income countries during their visit to Peru, the contributions to local trainees’ education, and the treatment of underserved patients. Furthermore, we discuss the embedded challenges from these missions and the future perspective on long-term partnerships and sustainability.

Methods: This is a narrative review. We searched the literature in PubMed and Google Scholar about neurosurgical missions conducted in Peru.

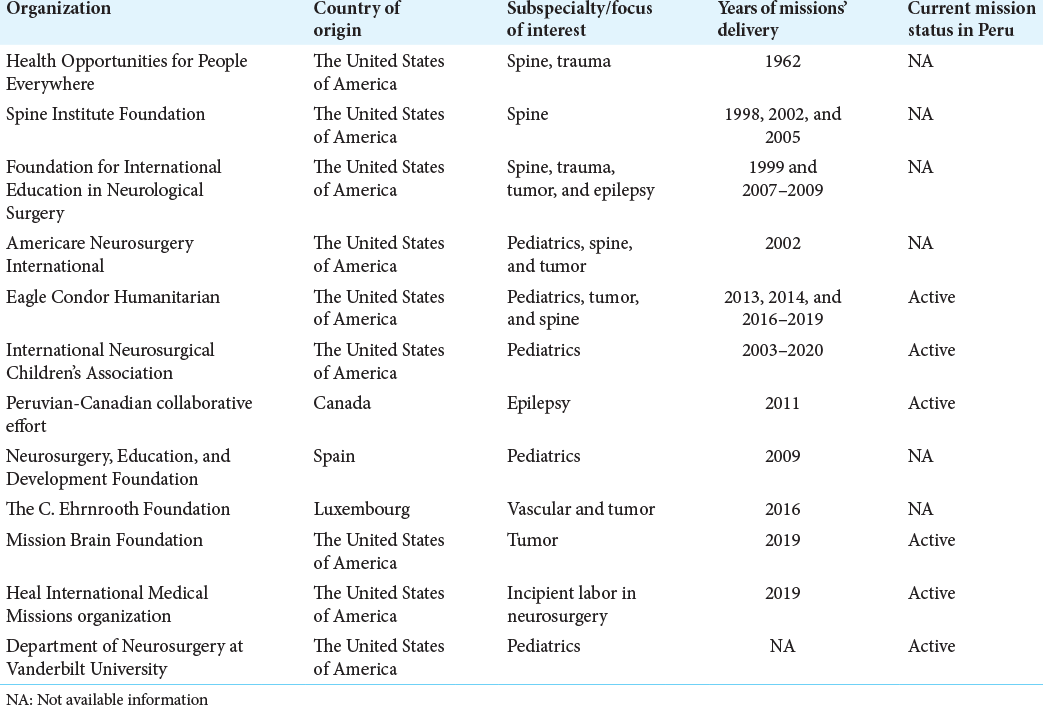

Results: Since 1962, twelve organizations from high-income countries have delivered humanitarian help in Peru by training local neurosurgeons, treating low-income patients, and providing surgical instrumentation. Out of the three main regions of Peru, cities on the coast and highlands have hosted most of these missions, with no reported outreach in the amazon area. About 75% of the organizations are headquartered in the United States, followed by Canada, Luxembourg, and Spain. In addition, 50% of the organizations have an active partnership. The predominant focus of these missions has been pediatrics, neuro-oncology, and spine surgery.

Conclusion: Neurosurgical missions have represented a strategy to close the disparity in education and treatment in Peru. However, additional efforts must be conducted to improve long-term partnership and sustainability, such as adopting standardized indicators for progress tracking, incorporating remote technologies for continuous training and communication, and expanding partnerships in less attended areas.

Keywords: Altruism, Global neurosurgery, Medical missions, Peru

INTRODUCTION

In 2015, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery, due to the increased need for surgical and anesthesia care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), published an update on the state of surgical care and proposed solutions to overcome disparities.[

Neurosurgical missions have attempted to reduce the disparity in the access and training of the local workforce in developing countries. Although expensive, they have demonstrated to be a cost-effective solution to reduce the burden of neurosurgical diseases in poor communities.[

The chronicle of these experiences highlights the significant contribution to the treatment of Peruvian patients and the education of local trainees, especially of people living in areas with an absent neurosurgical workforce, modern equipment, or limited neurosurgical training. In addition, we describe future perspectives on long-term partnerships, progress tracking, and promotion of new collaborations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the literature in PubMed and Google Scholar about neurosurgical missions conducted in Peru. We included information in original articles, organizations’ annual reports, and websites.

RESULTS

Twelve organizations from high-income countries have delivered humanitarian help in cities on the coast and highlands of Peru by training local neurosurgeons, treating low-income patients, and providing surgical instrumentation [

Figure 1:

Outreach map of neurosurgical missions across Peru. AMCANI: Americare Neurosurgery International. FIENS: Foundation for International Education in Neurological Surgery. HOPE: Health Opportunities for People Everywhere. INCA: International Neurosurgical Children’s Association. NED: Neurosurgery, Education, and Development Foundation.

A chronicle of neurosurgical missions in Peru

Neurosurgical help onboard a ship

In 1958, Dr. William B. Walsh founded Project Health Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE) as a humanitarian relief organization to offer help worldwide. Peru was gratefully considered a guest country after a formal invitation by the North American Peruvian Medical Association president, Dr. Fernando Cabieses-Molina. Accordingly, in 1962 onboard a hospital ship, the “S.S. Hope,” Project HOPE delivered its first mission to the Americas in Trujillo.[

A worldwide organization that provides volunteering opportunities to neurosurgeons

The Foundation for International Education in Neurological Surgery (FIENS) was established in 1969 by a group of neurosurgeons willing to contribute to the development of neurosurgery in LMICs. It has served countries through volunteer neurosurgeons who teach on-site techniques, set new residency programs, and provide surgical assistance in operating rooms.[

Dr. Antonio Bernardo exemplified the FIENS mission when he embarked on a volunteer trip in 1999 and spent 14 months sharing his freshly acquired skills in residency and fellowship with local trainees in Peru. During this journey, he was surprised to find medical settings lacking computed tomography scans, the most basic surgical instruments, and neurosurgical personnel. Nevertheless, he contributed to installing several microsurgical dissection laboratories, participated in local congresses, and helped with surgeries in Lima and surrounding cities.[

Between 2007 and 2009, a neurosurgeon from India contacted the president of FIENS, Dr. Merwyn Bagan, to express his desire to become a volunteer. Following his religious faith and despite discouraging comments from friends about working in a remote location without monetary compensation, Dr. Krishan K. Bansal felt a call to make a difference in the lives of those less fortunate. Thus, after leaving his home country to pursue this campaign, he visited three cities in Northwest Peru, including Chiclayo, Piura, and Trujillo. Dr. Bansal was amazed by the lack of imaging equipment, the scarce local workforce, and the quality of life of patients suffering from burdensome neurological diseases. Fortunately, in what he called “the experience of a lifetime,” Dr. Bansal achieved to assist in spinal and head trauma surgeries, provided neurosurgical supplies in four national hospitals, and lectured about the impact of surgery as a curative option for epilepsy.[

Americare Neurosurgery International (AMCANI)

In 2000, AMCANI was founded to promote modern neurosurgical care in the developing countries while respecting communities’ worldviews. It has worked by providing neurosurgical training and developing appropriate resources, including physical therapy, rehabilitation skills, and nursing care.[

The Eagle Condor Humanitarian (ECH) Foundation

ECH was founded in 2003 by a group of volunteer board directors committed to improving the quality of life for families and communities, alleviating generational poverty, and producing opportunities for self-reliance in South American countries (e.g., Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia). Its expeditions’ goal has included assisting underprivileged people and training staff from local hospitals.[

A well-organized program devoted to children’s care

In 2003, Dr. Rahul Jandial founded the International Neurosurgical Children’s Association (INCA) in City of Hope, California.[

A Peruvian-Canadian collaborative effort

In 2008, the absence of a program for Epilepsy Surgery in Peru motivated a collaboration between the Partnering Epilepsy Centers in America; the North American Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy; the Western University in London, Canada; and “Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati” and “Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas” in Lima, Peru. Numerous efforts, visits, and grants gave rise to the establishment of the first epilepsy program in the nation in 2011, where an interdisciplinary team between neurologists and neurosurgeons was able to help patients suffering from this detrimental illness. Notably, the strong partnership overcame diverse challenges such as the lack of personnel and infrastructure to provide continuous functioning of the video electroencephalography unit, and the patient idiosyncrasy about the disease’s nature.[

The Neurosurgery, Education, and Development (NED) Foundation

The NED Foundation has promoted a neuroscience culture to improve technological development in health care, for instance, through the incorporation of mobile and portable systems for the endoscopic treatment of hydrocephalus. In November 2009, its global plan included visiting pediatric patients suffering from hydrocephalus and shunt complications in Lima. Thus, in alliance with FIENS and local Peruvian neurosurgeons, the NED Foundation organized conferences, short courses, and neuroendoscopic surgeries for children at “Hospital Daniel Alcides Carrión,” “Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño,” and “Hospital Edgardo Rebagliati Martins.”[

The C. Ehrnrooth Foundation

Named after Göran Albert Casimir Ehrnrooth and conceived as part of the Luxembourg Foundation in 2008, the C. Ehrnrooth Foundation has promoted a philanthropic commitment to scientific research and holistic education to individuals, institutes, organizations, and universities.[

”Treat, educate, and empower”

Since 2011, the Mission Brain foundation has provided neurosurgical training and supplies in underserved areas; their volunteer team has allowed the delivery of specialized neurosurgical care, resources, and education to patients and trainees worldwide.[

In February 2019, the Mission Brain team traveled to Lima to perform neurosurgery on two older women referred from Quillabamba, Cusco.[

Nowadays, Mission Brain continues empowering young generations through medical school chapters to share their mission globally.[

The Heal International Medical Missions (HIMM) organization

Working under a Christian belief of serving people, HIMM has visited impoverished locations to provide medical and surgical attention. In 2019, it aided people living in Cutervo, a rural and remote city without robust surgical workforce in the highlands of Peru. Dr. Juan M. Padilla, director of HIMM, has been very concerned about the consequences of living in those precarious conditions, where patients die traveling long distances to seek basic and complex neurosurgical care. Thankfully, HIMM has started a project in this underserved community to bring medical attention not only in neurosurgery but also in general surgery, internal medicine, family medicine, dentistry, among other specialties.[

An American Neurosurgery department and its role in Global Neurosurgery

The Department of Neurosurgery at Vanderbilt University offers one of the few Global Neurosurgery curriculums in the United States, thus, allowing residents and faculty members to help patients with difficult access to routinely available procedures in North America. The neurosurgical department delivers outreach missions in Tanzania/Zanzibar, Uganda, Malawi, and Peru. Besides, it offers research mentorship to neurosurgeons in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Rwanda. For example, every year, a team led by Dr. Bonfield, in partnership with plastic surgeons and anesthesiologists from “KomedyPlast,” travels to Peru to perform craniofacial surgeries for complex craniosynostosis and skull deformities at “Instituto Nacional de Salud del Niño - San Borja” in Lima.[

DISCUSSION

Geographical outreach, incipient efforts, and opportunities for collaboration

During our chronicle, we noticed that most neurosurgical missions had been conducted on the coast or highlands of Peru and have spared the amazon area, a historically unattended area with difficult territorial access. However, we found that a local organization, the “Yantalo Peru Foundation,” has attended to the non-neurosurgical needs in this area for several years. Its facilities are part of a global health campus that collaborates with international institutions. Besides, the local community and organization committee have guided volunteers, including physicians and students, to find the accommodations, meals, and the most efficient route to reach the hospital during missions. As activities reinitiate after the pandemic the future partnerships and the delivery of neurosurgical care for the first time might represent an excellent opportunity to direct efforts in the area (contact information can be found at

On the other hand, our historical review revealed that few missions had focused their attention on preventing and treating neurotrauma [

Sustainability and progress tracking

Although the impact of neurosurgical missions is noticeable on patients and local trainees, the lack of measurable and standardized indicators limits the evaluation of progress tracking and sustainability over the years. Except for the INCA organization, whose labor has been tracked for almost 15 years by measuring the number of procedures completed and neurosurgeons trained per year, most organizations had no available long-term information in this regard. Hence, the adoption of core indicators for monitoring universal access to safe, affordable surgical, and anesthesia may benefit the organizations’ goals during missions. For this purpose, the parameters suggested by the Lancet Commission in Global Surgery include access to timely essential surgery, specialist surgical workforce density, surgical volume, perioperative mortality, protection against impoverishing expenditure, and protection against catastrophic expenditure.[

Remote technological solutions to strengthen long-term partnerships

With the advancement of technologies in neurosurgery, virtual platforms open for networking have demonstrated to potentiate and facilitate global collaborations. This is the case of “Intersurgeon,” an internet-based platform with almost 800 members worldwide that has contributed to transcend in-person neurosurgical missions and promote virtual collaborations based on augmented reality.[

Likewise, incorporating remote software for neurosurgical assistance and education may constitute an important step for its broad application during missions. For instance, “Virtual interactive presence and augmented reality (VIPAR)” and “Proximie” software may represent a game-changer in continuing long-term partnerships and improving sustainability.[

CONCLUSION

Neurosurgical missions have represented a strategy to close the disparity in education and treatment in Peru. However, additional efforts must be conducted to improve long-term partnership and sustainability, such as adopting standardized indicators for progress tracking, incorporating remote technologies for continuous training and communication, and expanding partnerships in less attended areas.

Disclosures

The authors are affiliated with the Mission Brain Foundation as part of their medical school chapter at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. Also, this review was accepted as an abstract at the 2022 Congress of Neurological Surgeons Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Publication of this article was made possible by the James I. and Carolyn R. Ausman Educational Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Juan Padilla and Dr. Luis Vásquez for providing information about Heal International Medical Missions (HIMM) and the Yantalo Peru Foundation, respectively.

References

1. AMCANI. American Neurosurgery International. Available from: https://www.amcani.org [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 27].

2. Bernardo A. Humanitarian Work. Available from: https://www.antoniobernardomd.com/humanitarian-work.html [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 30].

3. Bell B. Annual Report 2019. Available from: https://irpcdn.multiscreensite.com/62d1fe59/files/uploaded/ECH%20Annual%20Report%202019.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

4. Bocanegra-Becerra JE, Castillo-Huerta NM, Vilca-Salas MI, editors. Letter to the editor: The establishment of a new chapter in the neurosurgical care of patients with limited resources in Peru. World Neurosurg. 2022. 158: 316-7

5. Cheatham M. Profiles in volunteerism: From India to Peru as a neurosurgeon volunteer. Surg Neurol. 2009. 72: 87-8

6. Cheatham M. Profiles in volunteerism Gary Heit, MD, PhD, and Americare Neurosurgery International. Surg Neurol. 2008. 69: 544-5

7. Choque-Velasquez J, Colasanti R, Baffigo-Torre V, SacietaCarbajo L, Olivari-Heredia J, Falcon-Lizaraso Y. Developing the first highly specialized neurosurgical center of excellence in Trujillo, Peru: Work in progress-results of the first four months. World Neurosurg. 2017. 102: 334-9

8. Clínica Delgado Noticias. Visita de Reconocidos Especialistas de Mayo Clinic a Clínica Delgado. Available from: https://clinicadelgado.pe/noticia/visita-de-reconocidos-especialistasde-mayo-clinic-a-clinica-delgado [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 28].

9. Davis MC, Can DD, Pindrik J, Rocque BG, Johnston JM. Virtual interactive presence in global surgical education: International collaboration through augmented reality. World Neurosurg. 2016. 86: 103-11

10. Duenas V, Hahn E, Aryan H, Levy M, Jandial R. Targeted neurosurgical outreach: 5-year follow-up of operative skill transfer and sustainable care in Lima, Peru. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012. 28: 1227-31

11. Eagle Condor Humanitarian. Who We Are Our Mission. Available from: https://www.eaglecondor.org/who-we-are-our-mission [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

12. Eagle Condor Humanitarian. Foundation Documents. Available from: https://www.eaglecondor.org/foundation-documents [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

13. Fondation de Luxembourg. Origins. Available from: https://www.fdlux.lu/en/page/origins [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 11].

14. Fondation de Luxembourg. The Ehrnrooth Fellowship. Available from: https://www.fdlux.lu/en/project/ehrnrooth-fellowship [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 11].

15. Hayden MG, Hughes S, Hahn EJ, Aryan HE, Levy ML, Jandial R. Maria Auxiliadora Hospital in Lima, Peru as a model for neurosurgical outreach to international charity hospitals. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011. 27: 145-8

16. Heal International Medical Missions. Bringing Healing to Hurting Bodies and Souls. Available from: https://www.himmonline.org [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 30].

17. Higginbotham G. Virtual connections: Improving global neurosurgery through immersive technologies. Front Surg. 2021. 8: 629963

18. Hirdman T. Philanthropy Letter. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/site/netfwd/Philanthropy_Letter_winter2017.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 11].

19. Howe J. Fifty years of HOPE: 2007, Annual Report of Project Hope. Available from: https://www.projecthope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2007ProjectHOPEAnnualReport.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

20. Jandial R, Narang P, Brun JD, Levy M. Optimizing international neurosurgical outreach missions: 15-year appraisal of operative skill transfer in Lima, Peru. Surg Neurol Int. 2021. 12: 425

21. Kooiman EP. The Bulletin of the Project HOPE Alumni Association. Available from: https://www.projecthope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ALUMNI-NEWSLETTER_SPRING-2012-copy.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

22. Maleknia P, Shlobin NA, Johnston JM, Rosseau G. Establishing collaborations in global neurosurgery: The role of InterSurgeon. J Clin Neurosci. 2022. 100: 164-8

23. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015. 386: 569-624

24. Mission: Brain. Treat. Educate. Empower. Available from: https://www.missionbrain.org [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 28].

25. Mount LA. Peru and neurosurgery on project hope. J Neurosurg. 1963. 20: 512-4

26. NED. Neurocirugía. Available from: https://nedfundacion.org/?langen [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

27. Penn JW, Marcus HJ, Uff CE. Fifth generation cellular networks and neurosurgery: A narrative review. World Neurosurg. 2021. 156: 96-102

28. Project HOPE. Learn about Project HOPE. Available from: https://www.projecthope.org/about-us [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

29. Project HOPE. National Volunteer Week Meet Dr. Gregorio Delgado. Available from: https://www.projecthope.org/national-volunteer-week-meet-dr-gregorio-delgado/04/2012 [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 09].

30. Proximie-Saving Lives by Sharing the World’s Best Clinical Practice. Available from: https://www.proximie.com [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 31].

31. Punchak M, Mukhopadhyay S, Sachdev S, Hung Y, Peeters S, Rattani A. Neurosurgical care: availability and access in low-income and middle-income countries. World Neurosurg. 2018. 112: e240-54

32. Punchak M, Lazareff J. Cost-effectiveness of short-term neurosurgical missions relative to other surgical specialties. Surg Neurol Int. 2017. 8: 37

33. Ravindra VM, Kraus KL, Riva-Cambrin JK, Kestle JR. The need for cost-effective neurosurgical innovation--a global surgery initiative. World Neurosurg. 2015. 84: 1458-61

34. Sadanah Trauma and Surgical Initiative. Peru Trauma Initiative STSI. Available from: https://www.stsiglobal.org/peruvian-trauma-initiative [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 27].

35. Shenai MB, Dillavou M, Shum C, Ross D, Tubbs R, Shih A. Virtual interactive presence and augmented reality (VIPAR) for remote surgical assistance. Neurosurgery. 2011. 68: 200-7 discussion 207

36. Steven DA, Vasquez CM, Delgado JC, Zapata-Luyo W, Becerra A, Barreto E. Establishment of epilepsy surgery in Peru. Neurology. 2018. 91: 368-70

37. Tesen F. Alfredo Quiñones: “El cerebro es complejo y nuestro entendimiento aún es prehistórico”. Available from: https://diariocorreo.pe/salud/alfredo-quinones-cerebro-complejo-nuestro-entendimiento-esprehistorico-808828 [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 28].

38. The Foundation for International Education in Neurological Surgery FIENS. Available from: https://www.fiens.org [Last accessed on, 2021 Dec 30].

39. The Spine Practice of J. Patrick Johnson. Available from: https://spine-practice.com [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 28].

40. Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Global Neurosurgery Department of Neurological Surgery. Available from: https://www.vumc.org/neurosurgerydept/global-neurosurgery [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 30].

41. Weill Cornell Medicine. Surgical Innovations Laboratory Neurological Surgery. Available from: https://neurosurgery.weill.cornell.edu/education/surgical-innovations-laboratory [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 30].