- Neurosurgical Clinic AOUP “Paolo Giaccone”, Post Graduate Residency Program in Neurologic Surgery, Department of Biomedicine Neurosciences and Advanced Diagnostics, School of Medicine, University of Palermo, Palermo,

- Department of Sciences for Promotion of Health and Mother and Child Care, Anatomic Pathology, University of Palermo, Unit of Pathology,

- Department of Biomedicine, Neuroscience and Advanced Diagnostic - University of Palermo, Unit of Radiology, Palermo, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Roberta Costanzo, Neurosurgical Clinic AOUP “Paolo Giaccone”, Post Graduate Residency Program in Neurologic Surgery, Department of Biomedicine Neurosciences and Advanced Diagnostics, School of Medicine, University of Palermo, 90127 Palermo, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_341_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Roberta Costanzo1, Massimiliano Porzio1, Rosa Maria Gerardi1, Caterina Napolitano2, Sandro Bellavia2, Maria Angela Pino1, Francesco Bencivinni3, Maria Aurelia Banco3, Rosario Maugeri1, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Ada Maria Florena2. Thoracic dumbbell spinal metastasis secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of unknown origin: Case report and literature review. 13-May-2022;13:199

How to cite this URL: Roberta Costanzo1, Massimiliano Porzio1, Rosa Maria Gerardi1, Caterina Napolitano2, Sandro Bellavia2, Maria Angela Pino1, Francesco Bencivinni3, Maria Aurelia Banco3, Rosario Maugeri1, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Ada Maria Florena2. Thoracic dumbbell spinal metastasis secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of unknown origin: Case report and literature review. 13-May-2022;13:199. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11591/

Abstract

Background: Dumbbell tumors are typically benign schwannomas, neurofibromas, and meningiomas and only rarely there are malignant variants of these lesions or other malignant histotypes. Here, a 34-year-old male presented with a thoracic spinal dumbbell metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary origin.

Case Description: A 34-year-old male presented with 2 months of thoracic pain and progressive mid thoracic sensory loss. A post contrast thoracic MRI showed a dumbbell tumor localized between the T7 and T9 levels with extension laterally into the T7-T8 and T8-T9 foramina. The patient underwent a laminectomy for tumor resection following which his pain and gait improved. Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrated multiple rounded small cells with a Ki67 level around 30%, suggesting a malignant metastatic neuroendocrine tumor of unknown etiology.

Conclusion: We successfully treated a 34-year-old male with a T7-T9 malignant spinal dumbbell neuroendocrine tumor of unknown etiology utilizing a decompressive laminectomy.

Keywords: Dumbbell, Metastasis, Spine, Tumor

INTRODUCTION

Dumbbell tumors are typically benign schwannomas, neurofibromas, and meningiomas, with occasional malignant variants. Few dumbbell tumors are metastatic neuroendocrine lesions of unknown etiology.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

Clinical and radiographic presentation

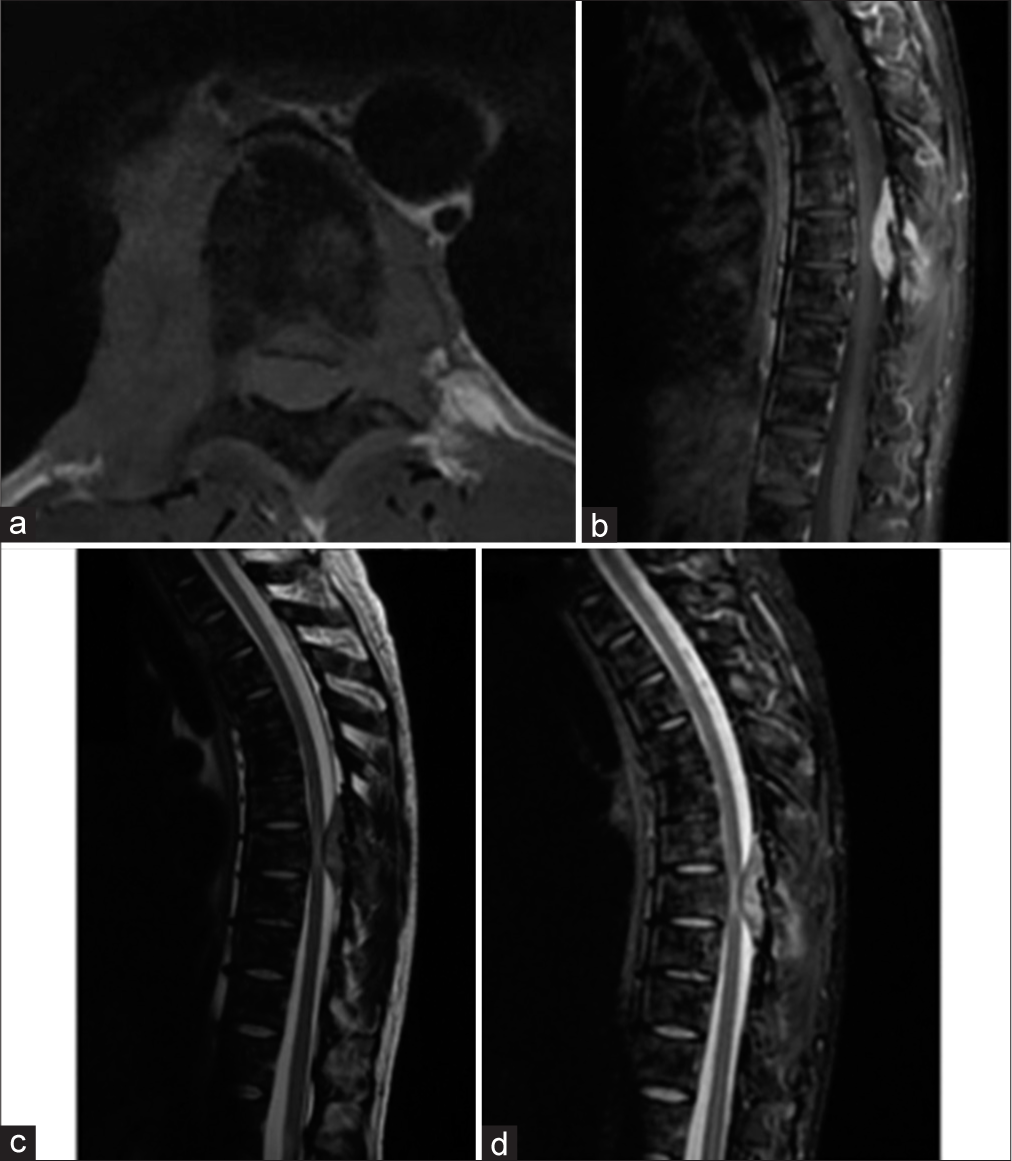

A 34-year-old male presented 2 months of mid thoracic pain, gait impairment/ataxia, and hypoesthesia from T11 downward. A post contrast thoracic MRI showed a dumbbell tumor between the T7 and T9 (i.e., maximal width T8) levels contributing to severe spinal cord compression [

Tumor markers

Blood tumor markers, that included beta-2-microglobulin, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and human chorionic gonadotropin-beta, were negative. Alternatively, serum neuron-specific enolase levels were high (48.4 µg/L; normal range: 0–16.3 µg/L) consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor origin.

Surgery

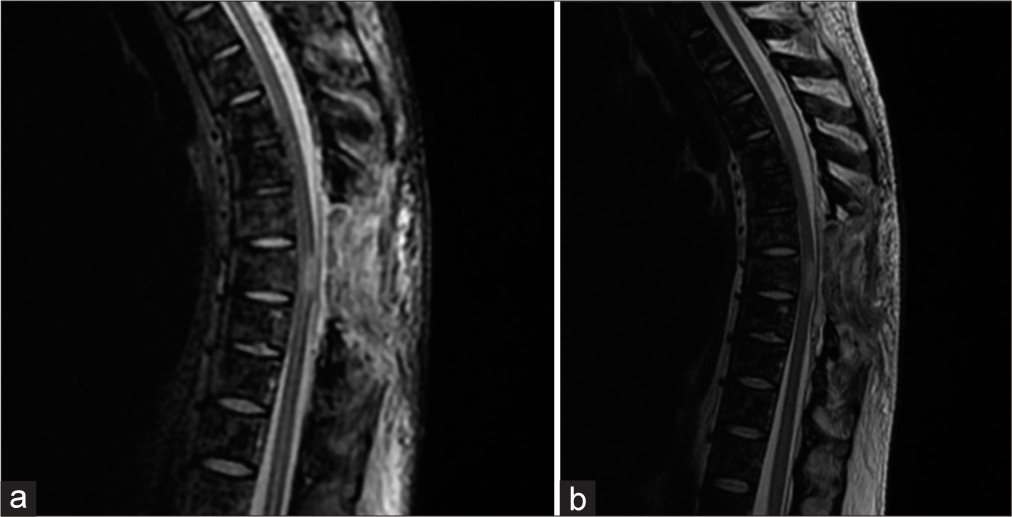

The patient underwent a T8 total/partial T7-T9 laminectomies to decompress the spinal cord. The tumor was hyper vascularized and there were significant adhesions between the tumor and the dura mater. Ultimately, a partial resection of the extradural lesion was accomplished. Postoperatively, the patient’s gait disturbance and dorsal pain were improved. The 1-week postoperative thoracolumbar MRI documented complete removal of the extradural tumor [

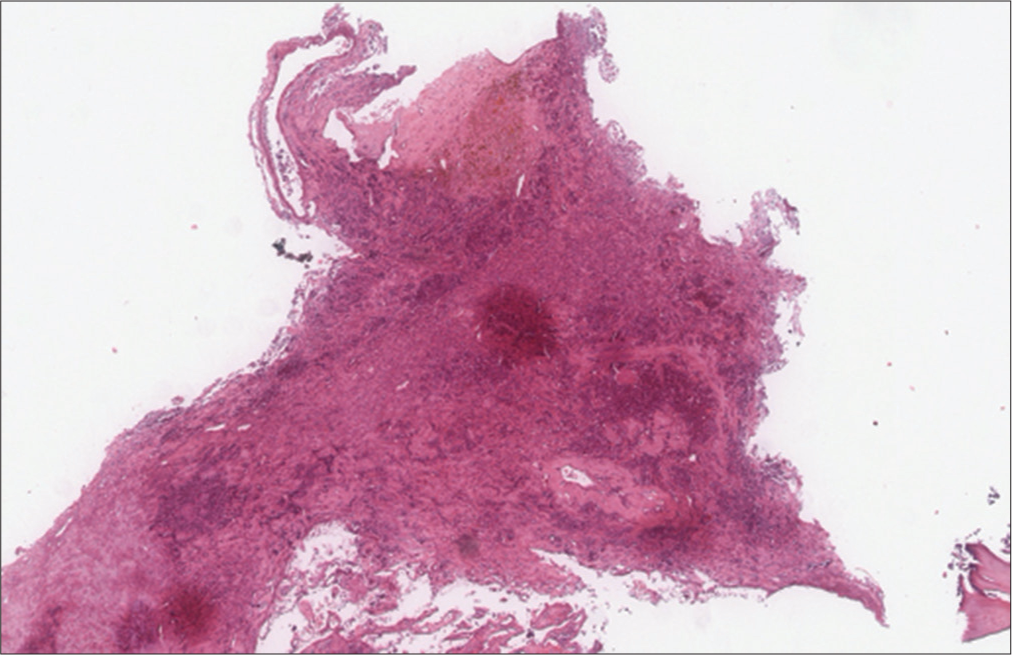

Histology

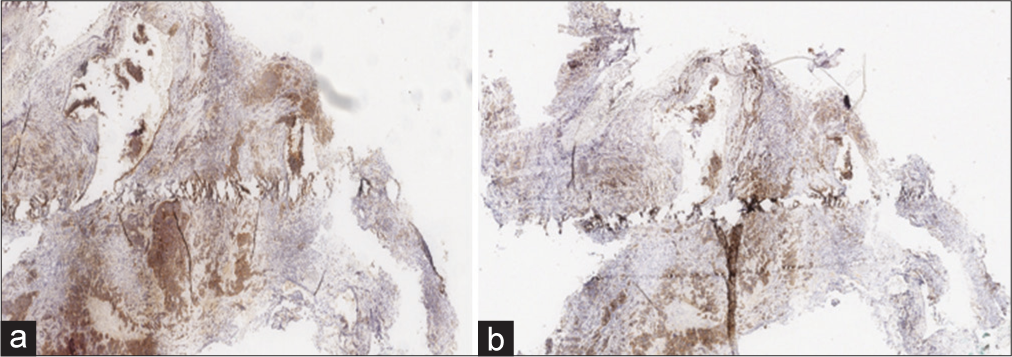

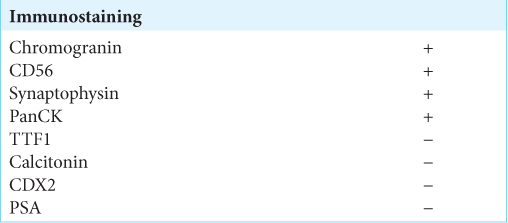

The histopathological examinations showed multiple round-small cells whose Ki67 level was about 30%, compatible with a neuroendocrine tumor of unknown etiology. Immunostaining showed a positive check for chromogranin and synaptophysin [

Figure 3:

Immunostaining showed the two most specific and sensitive markers capable of defining the neuroendocrine nature of the neoplasm: Synaptophysin: diffuse and intense cytoplasmic positivity in about 90% of neoplastic cells. (a) Chromogranin-A: granular cytoplasmic positivity (dot-like) in about 90% of neoplastic cells (b).

Postoperative course

The patient has started a chemotherapy (i.e., etoposide and cisplatin). After 10 months, his gait ataxia and lower limbs hyposthenia improved. At that point, he underwent a 68 Gallium-DOTATOC positron emission tomography/ computed tomography (PET/CT) that demonstrated stable disease.

DISCUSSION

Tumor presentation

According to the Dumbbell Scoring System, the neuroendocrine tumor presented in this case should be classified as a Grade 5 (size >5 cm, boundary indistinguishable, irregularly lobulated shape, and no osteolytic bone destruction) alternatively, it would belong to Grade 6 of the Eden classification (i.e. due to the multidirectional erosion of the bone).[

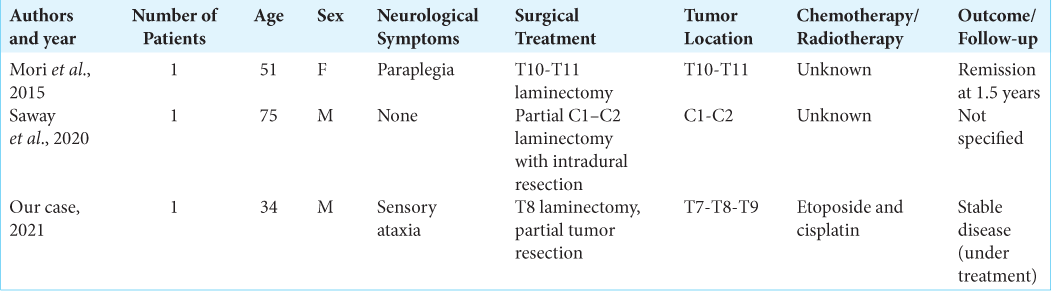

Cases of metastatic neuroendocrine dumbbell spine tumors

We found only two cases of comparable metastatic neuroendocrine dumbbell tumors of unknown origin in the literature.[

Markers used to identify of the etiology of neuroendocrine tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors of unknown etiology compromise approximately 10% of all NETs. As they are predominantly undifferentiated, their biological behavior is very aggressive.[

CONCLUSION

Here, we diagnosed a thoracic T7-T9 malignant metastatic spinal dumbbell neuroendocrine metastatic tumor of unknown origin in a 34-year-old male that was successfully treated with a laminectomy followed by chemotherapy.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Alexandraki K, Angelousi A, Boutzios G, Kyriakopoulos G, Rontogianni D, Kaltsas G. Management of neuroendocrine tumors of unknown primary. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017. 18: 423-43

2. Kaliya-Perumal AK, Tan M, Tee SW, Achudan S, Yap WM, Oh JY. Early post-surgical recurrence of metastatic vertebral neuro-endocrine tumour treated effectively with chemoradiotherapy. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2019. 9: 5

3. Matsumoto Y, Harimaya K, Kawaguchi K, Hayashida M, Okada S, Doi T. Dumbbell scoring system: A new method for the differential diagnosis of malignant and benign spinal dumbbell tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016. 41: E1230-6

4. Mori K, Nishizawa K, Nakamura A, Ishida M, Imai S. Sudden paraplegia because of dumbbell-shaped metastatic neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid tumor). Spine J. 2015. 15: e1-3

5. Oronsky B, Ma PC, Morgensztern D, Carter CA. Nothing but NET: A review of neuroendocrine tumors and carcinomas. Neoplasia. 2017. 19: 991-1002

6. Ozawa H, Kokubun S, Aizawa T, Hoshikawa T, Kawahara C. Spinal dumbbell tumors: An analysis of a series of 118 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007. 7: 587-93

7. Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016. 139: 2679-86

8. Saway BF, Fayed I, Dowlati E, Derakhshandeh R, Sandhu FA. Initial report of an intradural extramedullary metastasis of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor to the cervical spine: A case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2020. 139: 355-60

9. Scott S, Antwi-Yeboah Y, Bucur S. Metastatic carcinoid tumour with spinal cord compression. J Surg Case Rep. 2012. 2012: 5