- Department of Biomedicine Neurosciences and Advanced Diagnostics, Università degli Studi di Palermo Scuola di Medicina e Chirurgia, Palermo, Italy,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Tauli, Sabadell, Spain,

- Department of Neurosurgery, San Filippo Neri Hospital, Rome,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi di Varese, Varese,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Ospedale Sant’Eugenio, Rome, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Luciano Mastronardi, Department of Neurosurgery, San Filippo Neri Hospital, Rome, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_451_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Salvatore Marrone1, Julio Alberto Andres Sanz2, Guglielmo Cacciotti3, Alberto Campione4, Fabio Boccacci3, Flavia Fraschetti5, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Luciano Mastronardi3. Utility of sodium fluorescein in recurrent cervical vagus schwannoma surgery. 20-Oct-2023;14:376

How to cite this URL: Salvatore Marrone1, Julio Alberto Andres Sanz2, Guglielmo Cacciotti3, Alberto Campione4, Fabio Boccacci3, Flavia Fraschetti5, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Luciano Mastronardi3. Utility of sodium fluorescein in recurrent cervical vagus schwannoma surgery. 20-Oct-2023;14:376. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12605/

Abstract

Background: Cervical schwannoma is a rare neoplasm that usually occurs like a nondolent lateral neck mass but when growing and symptomatic requires radical excision. Sodium fluorescein (SF) is a dye that is uptake by schwannomas, which makes it amenable for its use in the resection of difficult or recurrent cases.

Methods: We describe the case of a patient presenting with a recurrence of a vagus nerve schwannoma in the cervical region and the step-by-step technique for its complete microsurgical exeresis helped by the use of SF dye.

Results: We achieved a complete microsurgical exeresis, despite the presence of exuberant perilesional fibrosis, by exploiting the ability of SF to stain the schwannoma and nearby tissues. That happens due to altered vascular permeability, allowing us to better differentiate the lesion boundaries and reactive scar tissue under microscope visualization (YELLOW 560 nm filter).

Conclusion: Recurrent cervical schwannoma might represent a surgical challenge due to its relation to the nerve, main cervical vessels, and the scar tissue encompassing the lesion. Although SF can cross both blood–brain and blood–tumor barriers, the impregnation of neoplastic tissue is still greater than that of nonneoplastic peripheric tissues. Such behavior may facilitate a safer removal of this kind of lesion while respecting contiguous anatomical structures.

Keywords: Cervical carotid lodge, Cervical vagus schwannoma, Neck vascular-nervous fascicle, Sodium fluorescein, Transcervical approach

INTRODUCTION

Cervical schwannomas are rare tumors with a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years of age, regardless of gender. They originate from Schwann cells of peripheral nerve sheaths. Schwannomas of the carotid lodge can originate from either the vagus nerve or the sympathetic plexus.[

CASE PRESENTATION

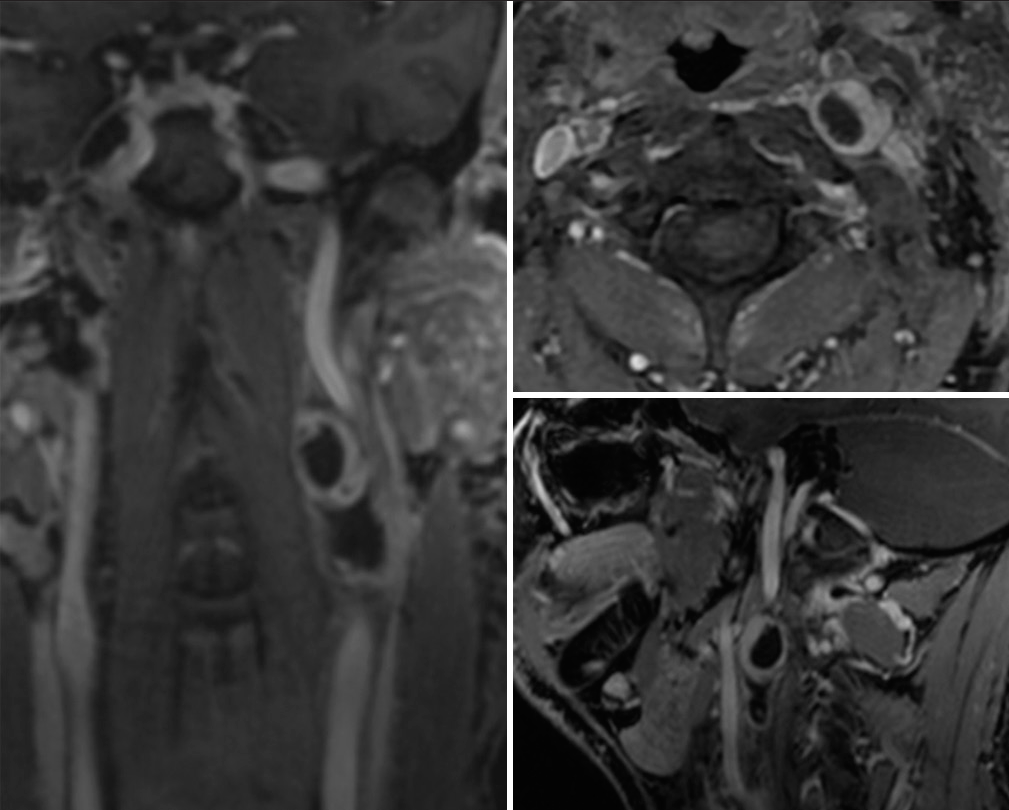

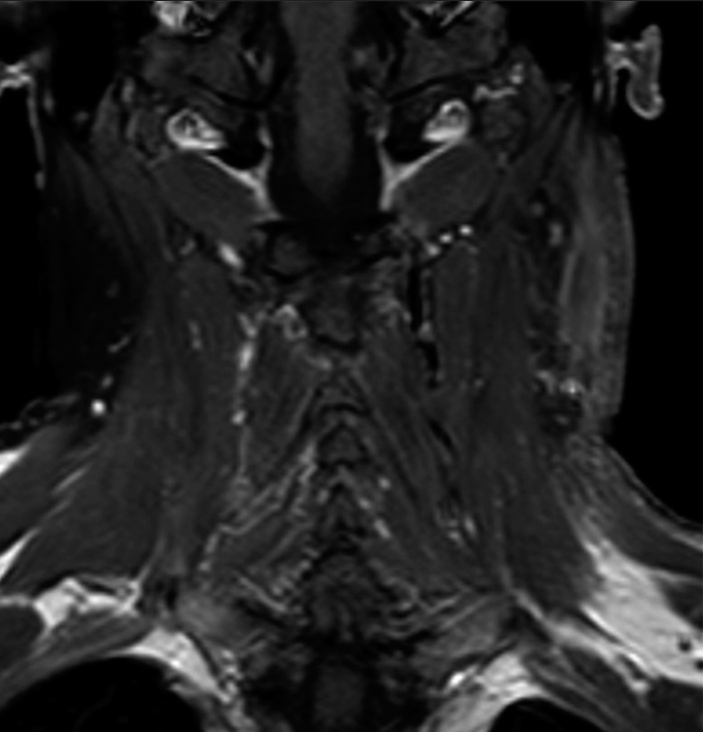

A 57-year-old man, 80 kg body weight, with a previous history of cervical schwannoma (47 mm × 32 mm × 25 mm), previously treated in another institution with subtotal exeresis, 18 months before consulting. The tumor was located in the left carotid space posterior to the vascular-nervous bundle of the neck, attached to the anterolateral vertebral surface. In the previous 6 months, the patient had referred difficulty in swallowing and phonation. At follow-up 1 year after surgery, magnetic resonance (MR) documented the presence of scar tissue in the left carotid region with an oval-shaped lesion (37 mm × 18 mm × 22 mm) displacing anteriorly the vascular-nervous bundle; tightly adherent to the carotid artery and jugular vein sheaths, the latter appearing pervious although reduced in caliber due to compression [

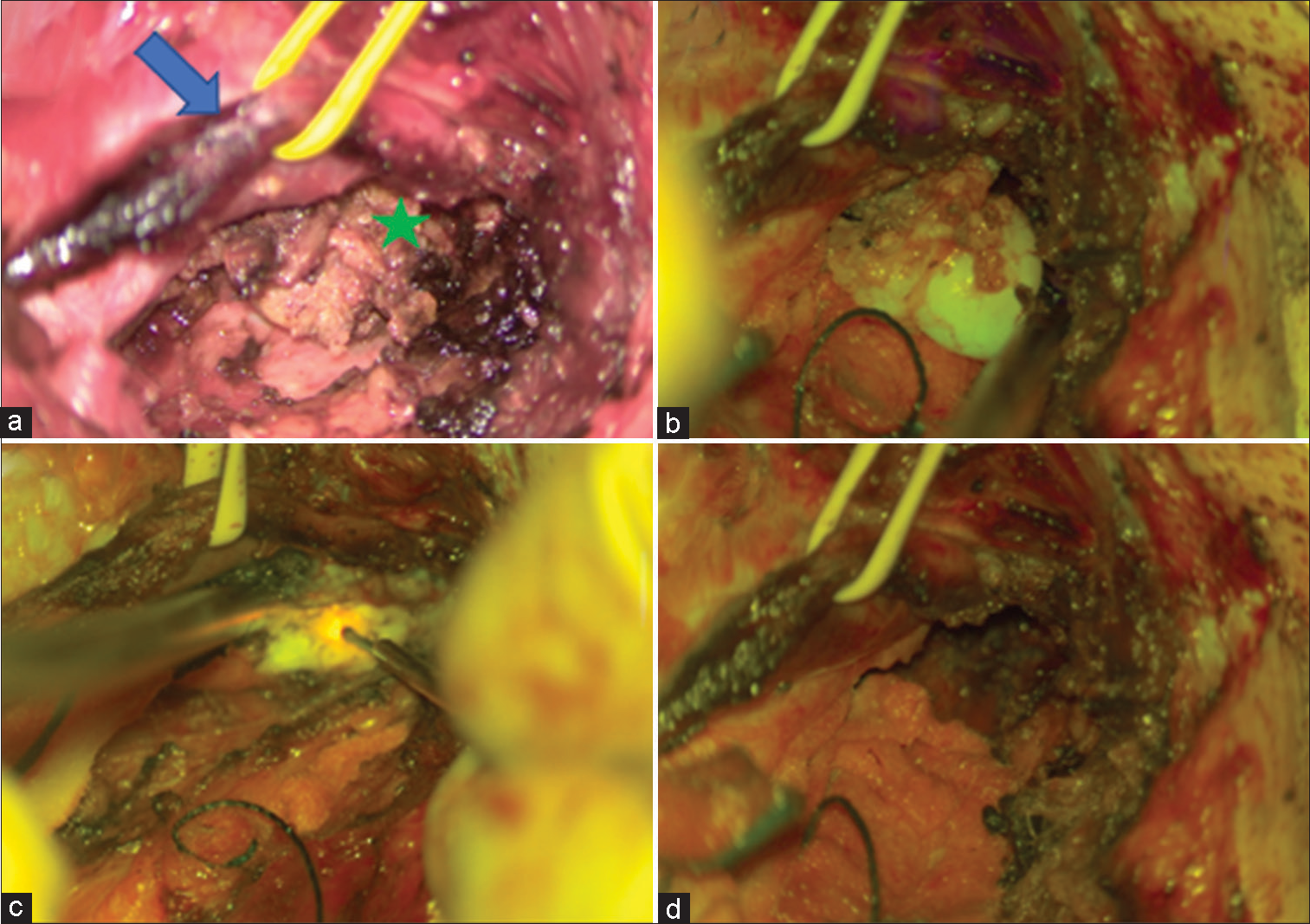

Figure 2:

Intraoperative images of cervical vagus schwannoma: (a) Tumor exposure after dissection. The carotid artery is reflected with a vessel loop (blue arrow). A tumor is shown underneath the vascular complex (green star). (b) Tumor vision under yellow fluorescence. (c) The tumor under debulking maneuvers during resection and (d) surgical cavity after tumor total resection; we can observe there is no longer fluorescein uptake.

Operative nuances

The patient was positioned in a supine position with the neck in extension and partially rotated to the right. Incision over the previous surgical presternocleidomastoid scar slightly extended upward toward the mandibular angle and downward beyond the plane passing through the cricoid (C6). An oblique incision was made on the platysma muscle, which appeared fibrotic and sclerotic. At this time, an intravenous bolus of 400 mg SF (5 mg/kg) was administered. Considering anatomical landmarks the sternocleidomastoid medial border and the cervical midline, blunt dissection of the carotid triangles (trigonus anterius colli) was performed. With ultrasound echography the internal jugular vein is immediately identified, appearing dilated over a stenotic tract and with a tortuous course. Proceeding with microsurgical dissection, the carotid artery was reached posteriorly; at this step, the lesion begins to be glimpsed in fluorescence (using the YELLOW-560 nm microscope filter) [

After checking the safety of the intended entry zone through electrophysiological monitoring the first capsule opening was performed, followed by central debulking employing an ultrasonic aspirator. With the help of fluorescence, it was possible to distinguish tumor from fibrosis and to identify the vital cleavage plane between the lesion and the vagus nerve. After generous debulking of the mass, the tumor capsule appears to be inwardly slackened, which facilitates the identification of the implantation base and its resection. Then the lesion was circumferentially dissected and piecemeal resected until gross total resection.

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas of the carotid lodge can originate from either the vagus nerve or the sympathetic plexus. Neurinomas of the cervical sympathetic chain are generally small and one of the first cases was described by Callum in 1949.[

Histologically, we distinguish between a true tumor capsule layer and an epineurium-perineurium capsule (tumor-complex capsule layer).[

CONCLUSION

Schwannomas of the cervical vagus nerve are rare pathologies that require surgical removal. Recurrences after a first surgical treatment could involve severe difficulties in finding a safe cleavage plane and in complete exeresis, due to distorted anatomy by profuse pericapsular scaring. Therefore, SF is an important tool aiding in identifying tumor borders and gradually proceeding to debridement from scar adhesions and intracapsular dissection.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Abdulla FA, Sasi MP. Schwannomatosis of cervical vagus nerve. Case Rep Surg. 2016. 2016: 8020919

2. Adouly T, Adnane C, Oubahmane T, Rouadi S, Abada R, Roubal M. An unusual giant schwannoma of cervical sympathetic chain: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016. 10: 26

3. Anil G, Tan TY. Imaging characteristics of schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain: A review of 12 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. 31: 1408-12

4. Behuria S, Rout TK, Pattanayak S. Diagnosis and management of schwannomas originating from the cervical vagus nerve. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015. 97: 92-7

5. Callum EN. Neurinoma of cervical sympathetic chain. Br J Surg. 1949. 37: 117

6. Hashimoto S. Concept of inter-capsular resection for cervical schwannoma. J Jpn Soc Head Neck Surg. 2007. 17: 91-2

7. Kahraman A, Yildirim I, Kiliç MA, Okur E, Demirpolat G. Horner’s syndrome from giant schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain: Case report. B ENT. 2009. 5: 111-4

8. Kato H, Kanematsu M, Mizuta K, Aoki M, Kuze B, Ohno T. “Flow-void” sign at MR imaging: A rare finding of extracranial head and neck schwannomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010. 31: 703-5

9. Kishimoto S, Ferris RL, editors. Technique for excision of cervical schwannoma. Head and neck surgery. Netherlands: Wolter Kluwer; 2013. p. 81-91

10. Kuroiwa M, Yako T, Goto T, Higuchi K, Kitazawa K, Horiuchi T. Inter-capsular resection of cervical vagus nerve schwannoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2018. 54: 161-4

11. Lee SJ, Yoon ST. Ultrasonographic and clinical characteristics of schwannoma of the hand. Clin Orthop Surg. 2017. 9: 91-5

12. Lin J, Jacobson JA, Hayes CW. Sonographic target sign in neurofibromas. J Ultrasound Med. 1999. 18: 513-7

13. Martin TJ. Horner’s syndrome, Pseudo-Horner’s syndrome, and simple anisocoria. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007. 7: 397-406

14. Misra BK, Jha AK. Potential utility of sodium fluorescein can distinguish tumor from cranial nerves in vestibular schwannoma surgery. Neurol India. 2021. 69: 1087-8

15. Murley RS. A case of neurinoma of the vagus nerve in the neck. Br J Surg. 1948. 36: 101-3

16. Pedro MT, Eissler A, Schmidberger J, Kratzer W, Wirtz CR, Antoniadis G. Sodium fluorescein-guided surgery in peripheral nerve sheath tumors: First Experience in 10 cases of schwannoma. World Neurosurg. 2019. 124: e724-32

17. Restelli F, Bonomo G, Monti E, Broggi G, Acerbi F, Broggi M. Safeness of sodium fluorescein administration in neurosurgery: Case-report of an erroneous very high-dose administration and review of the literature. Brain Spine. 2022. 2: 101703

18. Romanchuk KG. Fluorescein. Physicochemical factors affecting its fluorescence. Surv Ophthalmol. 1982. 26: 269-83

19. Rosahl S, Bohr C, Lell M, Hamm K, Iro H. Diagnostics and therapy of vestibular schwannomas-an interdisciplinary challenge. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017. 16: Doc03

20. Smith EJ, Gohil K, Thompson CM, Naik A, Hassaneen W. Fluorescein-guided resection of high grade gliomas: A meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021. 155: 181-8.e7

21. Szczupak M, Peña SA, Bracho O, Mei C, Bas E, Fernandez-Valle C. Fluorescent detection of vestibular schwannoma using intravenous sodium fluorescein in vivo. Otol Neurotol. 2021. 42: e503-11

22. Vetrano IG, Nazzi V, Acerbi F. What is the advantage of using sodium fluorescein during resection of peripheral nerve tumors?. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020. 162: 1153-5

23. Zheng X, Guo K, Wang H, Li D, Wu Y, Ji Q. Extracranial schwannoma in the carotid space: A retrospective review of 91 cases. Head Neck. 2017. 39: 42-7

24. Zhu JE, Chen YC, Yu SY, Xu HX. The first experience of ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for extracranial schwannoma of the cervical vagus nerve in carotid space and treatment response evaluation with contrast-enhanced imaging: A case report. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2022. 80: 437-46