- Department of Neurosurgery, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Department of Medical Imaging, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Correspondence Address:

Brett Rocos

Department of Neurosurgery, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_311_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Chloe Gui1, Brett Rocos1, Laura-Nanna Lohkamp1, Angela Cheung2, Robert Bleakney3, Eric Massicotte1. Utility of the spinal instability neoplastic score to identify patients with Gorham-Stout disease requiring spine surgery. 17-May-2021;12:227

How to cite this URL: Chloe Gui1, Brett Rocos1, Laura-Nanna Lohkamp1, Angela Cheung2, Robert Bleakney3, Eric Massicotte1. Utility of the spinal instability neoplastic score to identify patients with Gorham-Stout disease requiring spine surgery. 17-May-2021;12:227. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10812/

Abstract

Background: Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) is a rare syndrome presenting with progressive osteolysis which in the spine can lead to cord injury, instability, and deformity. Here, the early spine surgery may prevent catastrophic outcomes.

Case Description: A 25-year-old male with GSD involving the T2 to T6 levels presented with acute traumatic kyphoscoliosis at T3 and T4 and left lower extremity paraparesis. The CT scan 4 weeks before this showed progressing osteolysis versus the CT 5 years ago. Unfortunately, the patient underwent delayed treatment resulting in permanent neurological sequelae. Surgery included a laminectomy and vertebrectomy of T3/T4 with instrumented fusion from T1-10. The use of the spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS) is a useful tool to prompt early referral to spine surgeons.

Conclusion: We recommend using the SINS score in GSD patients who develop spinal lesions to prompt early referral for consideration of surgery.

Keywords: Gorham-Stout, Instability, Reconstruction, Spine

BACKGROUND AND IMPORTANCE

Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) is rare; only approximately 300 cases have been reported.[

Spinal involvement has been reported in 75 patients, 33 of which required surgery for fracture or deformity.[

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A 25-year-old male with GSD presented with traumatic kyphoscoliosis centered at the T3-T4 level.[

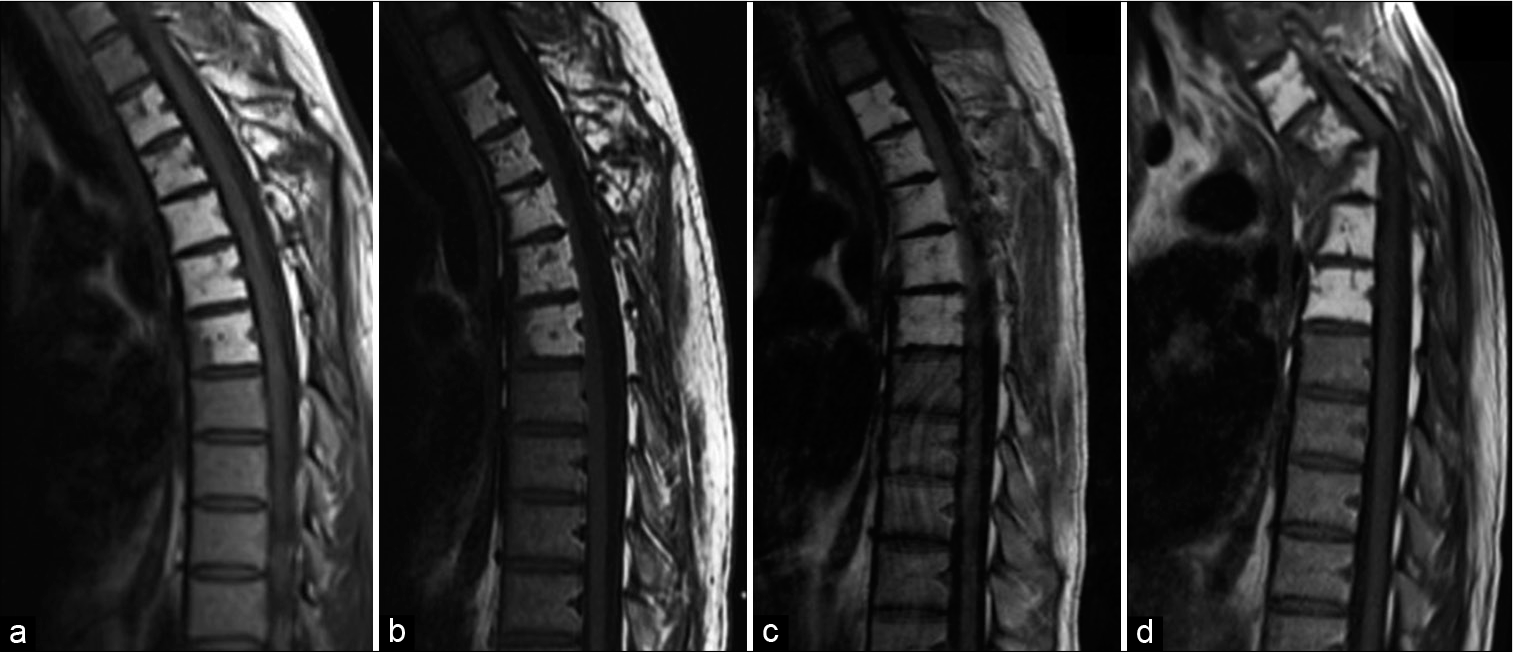

Figure 1:

Annual MR imaging of the thoracic spine over 3 years (a-c) demonstrates stability of the increased signal intensity of the T2-T6 vertebral bodies, which is consistent with the fatty marrow replacement seen in Gorham-Stout disease. Postinjury imaging (d) demonstrates severe kyphosis at T3-T4. Acute cord signal change is evident, in keeping with acute myelopathy (d).

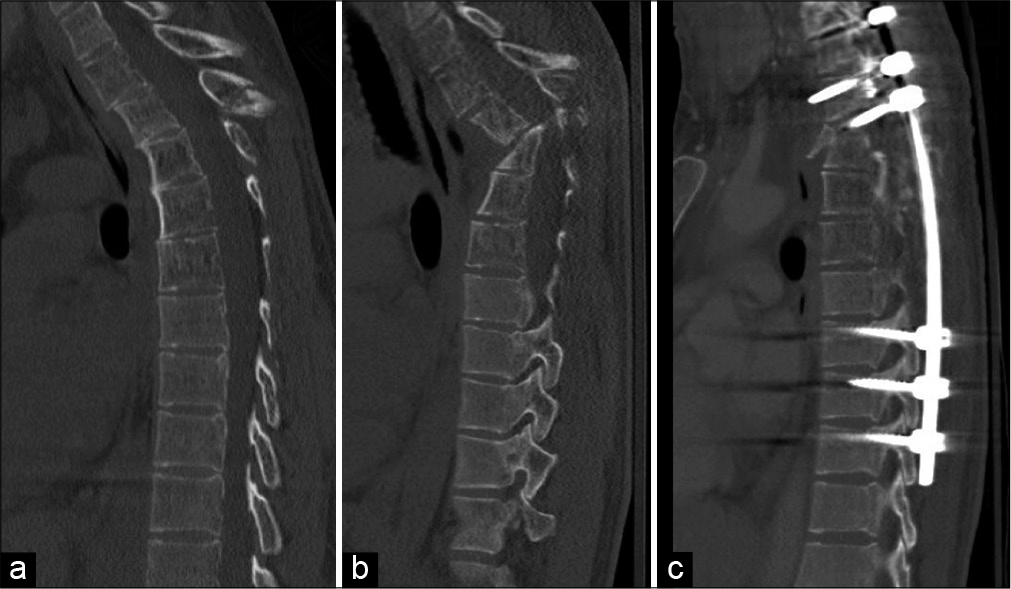

Figure 2:

CT imaging shows the T3 spinous fracture (a) sustained 1 month before further pathologic kyphotic angulation deformity at T3-T4 with extensive destruction of the posterior elements (b). Postoperative CT imaging demonstrates instrumented fusion from T1-T10 with significant improvement in kyphotic deformity at T3-4 (c).

The patient underwent a partial vertebrectomy at T3 and T4 and posterior instrumented fusion from T1 to T10 [

DISCUSSION

The timing of surgery in the treatment of GSD is challenging. Operating while the disease is active is not a definitive management because instability or neurological deficits may occur as osteolysis progresses.[

The spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS) was initially developed to determine instability of the vertebral column due to metastatic tumor burden visible on CT. It is easy to use for nonsurgical personnel in an inpatient or outpatient setting using standard investigations to identify and quantify spinal instability with patients scoring “potential instability” or “instability” being referred for an urgent surgical opinion. If employed in cases of GSD, the score could serve as a tool to trigger early consultation with a spine surgeon before symptomatic spinal instability or neurological compromise.[

CONCLUSION

In GSD patients with known spinal lesions, we recommend serial evaluation of stability using the SINS and involving a spine surgeon early to prevent progressive instability, deformities, and neurologic deficits.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bode-Lesniewska B, von Hochstetter A, Exner GU, Hodler J. Gorham-Stout disease of the shoulder girdle and cervicothoracic spine: Fatal course in a 65-year-old woman. Skeletal Radiol. 2002. 31: 724-9

2. Bruch-Gerharz D, Gerharz CD, Stege H, Krutmann J, Pohl M, Koester R. Cutaneous lymphatic malformations in disappearing bone (Gorham-Stout) disease: A novel clue to the pathogenesis of a rare syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007. 56: S21-5

3. Campbell J, Almond HG, Johnson R. Massive osteolysis of the humerus with spontaneous recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975. 57: 238-40

4. Chang KJ, Yang MH, Li B, Huang H. Surgical management of Gorham-Stout syndrome involving the cervical spine with bilateral pleural effusion: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2020. 19: 3851-5

5. Drewry GR, Sutterlin CE, Martinez CR, Brantley SG. Gorham disease of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994. 19: 2213-22

6. Du CZ, Li S, Xu L, Zhou QS, Zhu ZZ, Sun X. Spinal Gorham-Stout syndrome: Radiological changes and spinal deformities. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019. 9: 565-78

7. Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, Bilsky MH, Shaffrey CI, Berven SH. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: An evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine oncology study group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010. 35: E1221-9

8. Kim JH, Yoon DH, Kim KN, Shin DA, Yi S, Kang J. Surgical management of gorham-stout disease in cervical compression fracture with cervicothoracic fusion: Case report and review of literature. World Neurosurg. 2019. 129: 277-81

9. Koto K, Inui K, Itoi M, Itoh K. Gorham-Stout disease in the rib and thoracic spine with spinal injury treated with radiotherapy, zoledronic acid, Vitamin D, and propranolol: A case report and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019. 11: 551-6

10. Lala S, Mulliken JB, Alomari AI, Fishman SJ, Kozakewich HP, Chaudry G. Gorham-Stout disease and generalized lymphatic anomaly--clinical, radiologic, and histologic differentiation. Skeletal Radiol. 2013. 42: 917-24

11. Lam D, Wong EM, Cheung AM, Lakoff JM. Gorham-stout disease: Case report and suggested diagnostic evaluation of a rare clinical entity. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2018. 4: 166-70

12. Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): A review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014. 5: 694-8

13. Radhakrishnan K, Rockson SG. Gorham’s disease: An osseous disease of lymphangiogenesis?. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008. 1131: 203-5

14. Reddy S, Jatti D. Gorham’s disease: A report of a case with mandibular involvement in a 10-year follow-up study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012. 41: 520-4

15. Tateda S, Aizawa T, Hashimoto K, Kanno H, Ohtsu S, Itoi E. Successful management of gorham-stout disease in the cervical spine by combined conservative and surgical treatments: A case report. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2017. 241: 249-54