- Department of Neurosurgery, Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Naoki Ikegaya, Department of Neurosurgery, Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1120_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Misaki Kamogawa, Naoki Ikegaya, Yohei Miyake, Takahiro Hayashi, Hidetoshi Murata, Kensuke Tateishi, Tetsuya Yamamoto. Verbal and memory deficits caused by aphasic status epilepticus after resection of a left temporal lobe glioma. 14-Dec-2021;12:614

How to cite this URL: Misaki Kamogawa, Naoki Ikegaya, Yohei Miyake, Takahiro Hayashi, Hidetoshi Murata, Kensuke Tateishi, Tetsuya Yamamoto. Verbal and memory deficits caused by aphasic status epilepticus after resection of a left temporal lobe glioma. 14-Dec-2021;12:614. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11285/

Abstract

Background: Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) is induced by common neurosurgical conditions, for example, trauma, stroke, tumors, and surgical interventions in the brain. The aggressiveness of the treatment for NCSE depends on its neurological prognosis. Aphasic status epilepticus (ASE) is a subtype of focal NCSE without consciousness impairment. The impact of ASE on neurological prognosis is poorly documented. We describe a case of postoperative ASE resulting in verbal and memory deficits.

Case Description: A 54-year-old, right-handed man with focal impaired awareness seizures underwent partial resection for a left temporal lobe tumor. No neurological deficits were observed immediately after surgery. Three days later, however, a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (FBTCS) occurred, followed by aphasia. Electroencephalography revealed 1.5 Hz left-sided periodic discharges. He was diagnosed with ASE. Multiple anti-seizure drugs were ineffective for the resolution of the patient’s verbal disturbance. Nine days after the FBTCS, deep sedation with intravenous anesthetics was performed and the ASE stopped. Thereafter, his symptoms gradually improved. However, the prolonged ASE resulted in verbal and memory deficits. Automated hippocampal volumetry revealed an approximate decrease of 20% on the diseased side on magnetic resonance imaging 3 months after surgery.

Conclusion: Prolonged ASE can induce verbal and memory deficits. Early intervention with intravenous anesthetics is required to obtain a favorable neurological prognosis.

Keywords: Aphasic status epilepticus, Intravenous anesthetics, Memory disturbance, Nonconvulsive status epilepticus, Verbal deficit

INTRODUCTION

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) has been attracting increasing attention in neurosurgical practice after the Salzburg criteria were published.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

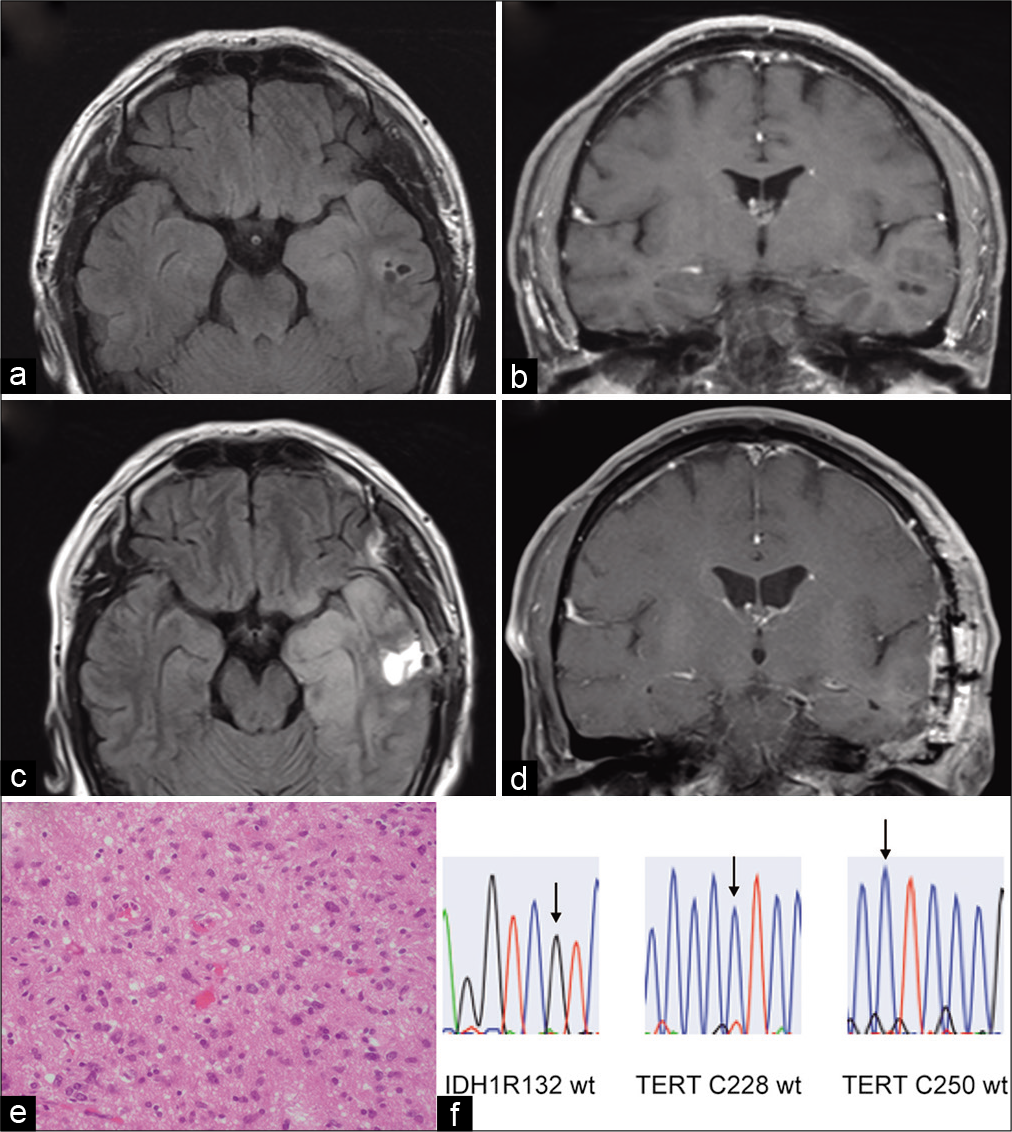

A 54-year-old, right-handed man had experienced two episodes of focal impaired awareness seizures and was taking levetiracetam. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a high-intensity lesion of the temporal lobe on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery-weighted images, and a noncontrast-enhanced cyst appeared inside the temporal lobe at the 1-year follow-up, suggesting the presence of a low-grade brain tumor [

Figure 1:

(a) Preoperative fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging (FLAIR-MRI) revealing a high-intensity area with a cyst component in the left temporal lobe. (b) Preoperative contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1WCE) MRI revealing no enhancement. (c) Postoperative FLAIR-MRI indicating the partial removal of the tumor. (d) Postoperative T1WCE-MRI. Note that the inferior horn of the left lateral ventricle is enlarged. This may be explained by a reduction in the mass effect and hippocampal volume loss [Table 1]. (e) The hematoxylin-andeosin-stained specimen is consistent with an astrocytic glioma. (f) Genomic analysis indicates that the IDH gene and TERT promoter are wild type.

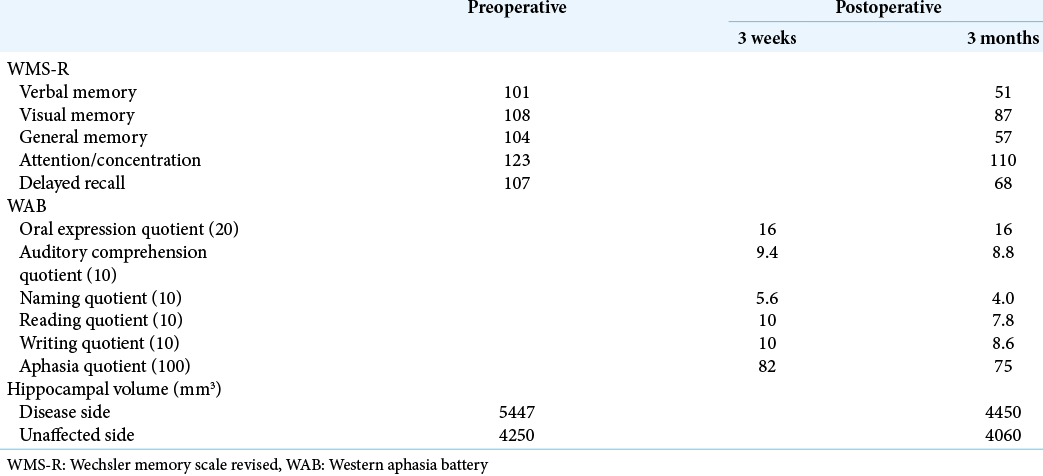

No neurological deficits were observed immediately after surgery. However, 3 days later, a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (FBTCS) occurred, followed by aphasia. The verbal disturbance was initially presumed to be a part of the postictal state; however, these symptoms persisted even as his eating, walking, and comprehension returned to baseline levels. The presence of ischemic complications was excluded using diffusion-weighted MRI. This suggested that NCSE, such as ASE, could be responsible for the language disturbance. Therefore, levetiracetam was increased to the maximum dosage of 3000 mg/day, and lacosamide was additionally administered at 200 mg/day. However, their efficacy was limited. Four days after the FBTCS, EEG revealed 1.5 Hz left-sided periodic discharges (PDs) and ictal spatiotemporal evolution of rhythmic activity, which demonstrated that the ASE persisted [

Figure 2:

(a) An electroencephalograph (EEG; longitudinal bipolar montage), taken 4 days after the focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure, reveals 1.5 Hz periodic discharges with a maximum amplitude in the left temporal area. (b) An EEG revealing spatiotemporal evolution of epileptic discharges, indicating nonconvulsive status epilepticus (blue: periodic discharges, yellow: temporal evolution, green: spatial evolution). Lt: Left, Rt: Right, Fp: Front polar, F: Frontal, C: Central, P: Parietal, O: Occipital, pT: Posterior temporal, mT: Mid-temporal, aT: Anterior temporal, Md: Midline.

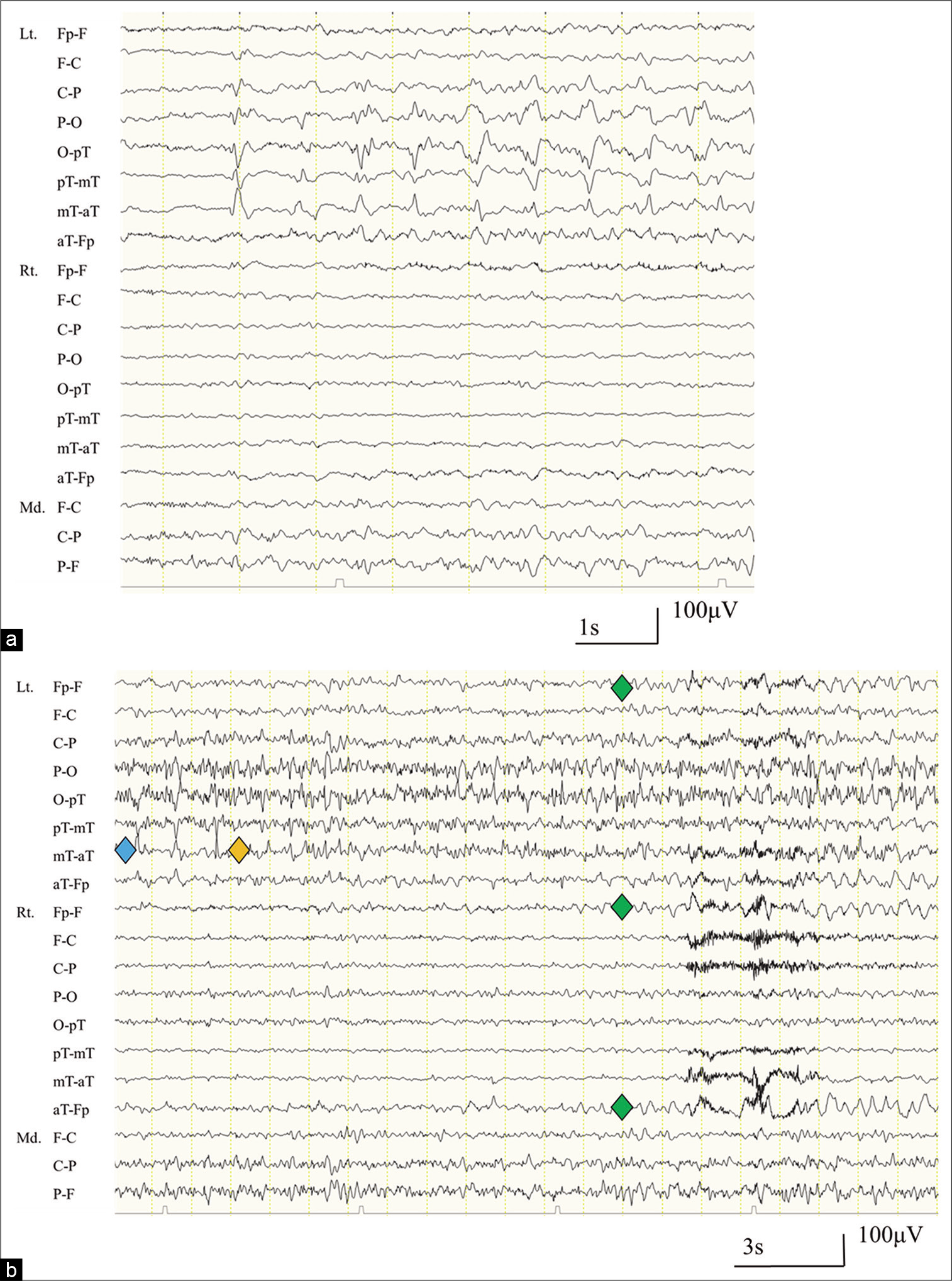

In addition, a decrease in the indices of the WMS-R demonstrated substantial memory impairment after the prolonged ASE. Automated hippocampal volumetry, conducted with the FreeSurfer software suite (

DISCUSSION

We describe a case of ASE after surgery for a glioma in the left temporal lobe that resulted in verbal and memory sequelae. The clinical course of the patient demonstrates two important clinical issues. First, focal NCSE without consciousness impairment, such as ASE, can induce verbal and memory deficits. Second, intravenous anesthetics can halt ASE; however, early intervention is required for a favorable neurological prognosis.

ASE is a subtype of focal NCSE that is not accompanied by impaired consciousness, and it induces verbal disturbance during status epilepticus. While NCSE with coma or impaired awareness is notorious for poor neurological prognoses, verbal disturbance caused by ASE normally resolves, even if improvement is gradual.[

The association between ASE and memory sequelae remains unclear. Complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), another subtype of NCSE, can cause permanent cognitive and memory dysfunction.[

In this study, intravenous anesthetics halted ASE that was refractory to multiple ASDs.[

Although early intervention is required for a favorable neurological prognosis, early detection of ASE remains challenging. Postoperative aphasia can result from common neurosurgical conditions, for example, ischemia, direct injury of the language area, Todd paresis, and NCSE, such as ASE. The combination of neuroimaging modalities and electrophysiological examinations can help to identify the cause. When an unexpected aphasia develops, MRI and EEG should be performed as early as possible. Continuous EEG (cEEG) has a higher diagnostic ability than normal EEG that is conducted for <1 h. If cEEG cannot be implemented, 2 h EEG is an alternative for capturing ictal activity in patients with NCSE.[

CONCLUSION

Prolonged ASE can induce verbal and memory impairments. Early intervention with intravenous anesthetics is required to obtain favorable neurological outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

JSPS Kakenhi (No. 19K18435).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Yuichi Higashiyama for his technical support in image analysis and Dr. Naoko Udaka for her clinical support.

References

1. Azman F, Tezer FI, Saygi S. Aphasic status epilepticus in a tertiary referral center in Turkey: Clinical features, etiology, and outcome. Epilepsy Res. 2020. 167: 106479

2. Chung PW, Seo DW, Kwon JC, Kim H, Na DL. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus presenting as a subacute progressive aphasia. Seizure. 2002. 11: 449-54

3. Dong C, Sriram S, Delbeke D, Al-Kaylani M, Arain AM, Singh P. Aphasic or amnesic status epilepticus detected on PET but not EEG. Epilepsia. 2009. 50: 251-5

4. Ericson EJ, Gerard EE, Macken MP, Schuele SU. Aphasic status epilepticus: Electroclinical correlation. Epilepsia. 2011. 52: 1452-8

5. Ferguson M, Bianchi MT, Sutter R, Rosenthal ES, Cash SS, Kaplan PW. Calculating the risk benefit equation for aggressive treatment of non-convulsive status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2013. 18: 216-27

6. Fernández-Torre JL, Figols J, Martínez-Martínez M, González-Rato J, Calleja J. Localisation-related nonconvulsive status epilepticus: Further evidence of permanent cerebral damage. J Neurol. 2006. 253: 392-5

7. Fernández-Torre JL, Pascual J, Quirce R, Gutiérrez A, Martínez-Martínez M, Rebollo M. Permanent dysphasia after status epilepticus: Long-term follow-up in an elderly patient. Epilepsy Behav. 2006. 8: 677-80

8. González-Cuevas M, Coscojuela P, Santamarina E, Pareto D, Quintana M, Sueiras M. Usefulness of brain perfusion CT in focal-onset status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2019. 60: 1317-24

9. Heinrich A, Runge U, Kirsch M, Khaw AV. A case of hippocampal laminar necrosis following complex partial status epilepticus. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007. 115: 425-8

10. Hocker S. Anesthetic drugs for the treatment of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2018. 59: 188-92

11. Leitinger M, Beniczky S, Rohracher A, Gardella E, Kalss G, Qerama E. Salzburg consensus criteria for non-convulsive status epilepticus-approach to clinical application. Epilepsy Behav. 2015. 49: 158-63

12. Qiu JQ, Cui Y, Sun LC, Zhu ZP. Aphasic status epilepticus as the sole symptom of epilepsy: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2017. 14: 3501-6

13. Rolak LA, Rutecki P, Ashizawa T, Harati Y. Clinical features of Todd’s post-epileptic paralysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992. 55: 63-4

14. Rossetti AO, Hirsch LJ, Drislane FW. Nonconvulsive seizures and nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the neuro ICU should or should not be treated aggressively: A debate. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2019. 4: 170-7

15. Shimogawa T, Morioka T, Sayama T, Haga S, Kanazawa Y, Murao K. The initial use of arterial spin labeling perfusion and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance images in the diagnosis of non-convulsive partial status epileptics. Epilepsy Res. 2017. 129: 162-73

16. Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE, Shinnar S. A definition and classification of status epilepticus-report of the ILAE task force on classification of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015. 56: 1515-23

17. Vespa PM, McArthur DL, Xu Y, Eliseo M, Etchepare M, Dinov I. Nonconvulsive seizures after traumatic brain injury are associated with hippocampal atrophy. Neurology. 2010. 75: 792-8